Exploring the Interactions Between Baby Marmosets and Their Caregivers

The findings can help understand how parenting impacts the formation of attachment and independence in human children

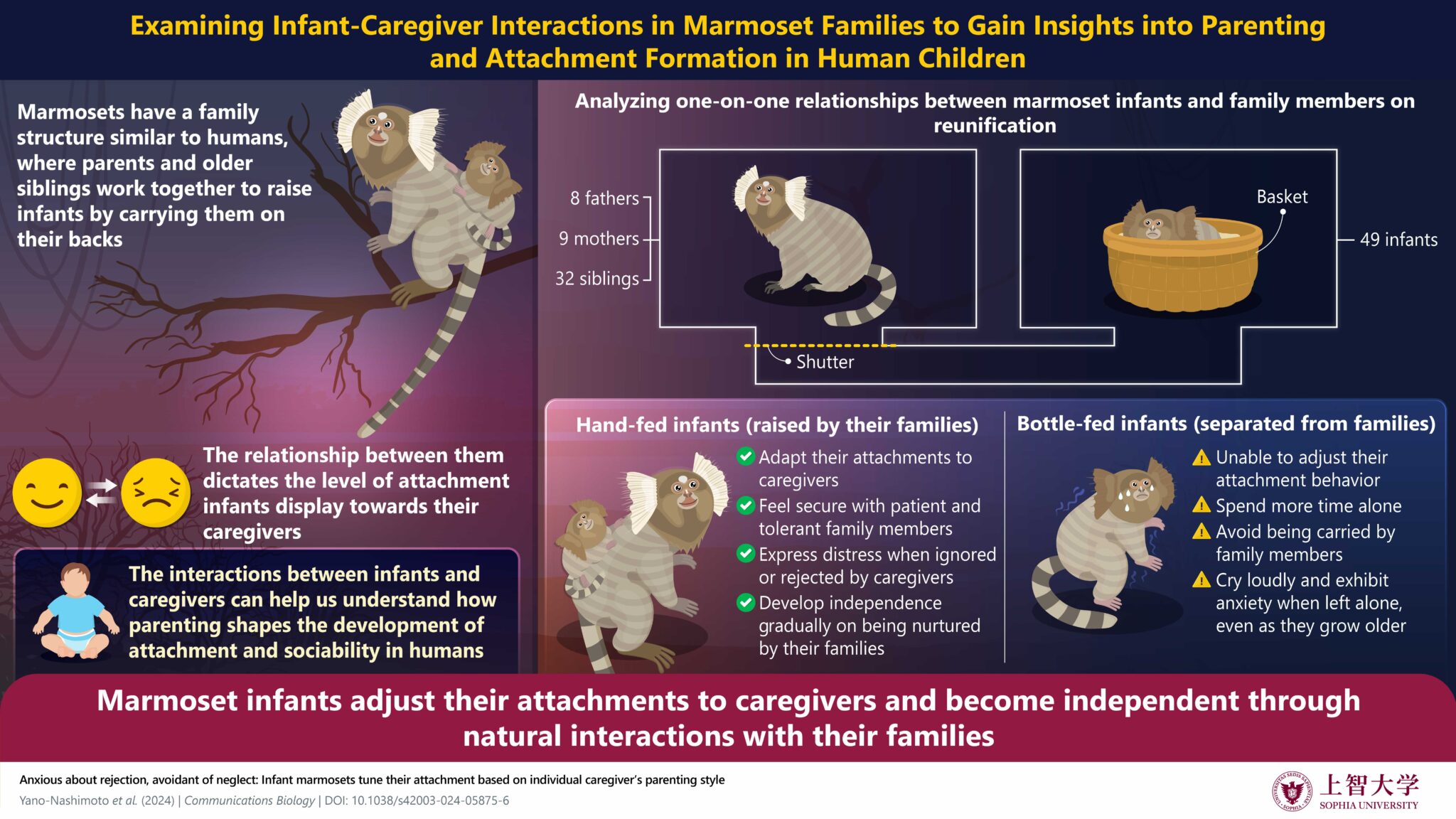

A child’s feeling of security is strongly influenced by the care they receive, influencing their development as they grow. To understand how parenting impacts attachment and independence in human children, researchers investigated how baby marmosets respond to various caregivers. They found that baby marmosets adapt their attachments and become more independent through interactions with their families. These insights can inform better parenting practices and support for childcare in human society.

The connection that infants form with their parents or caregivers is crucial for their cognitive, social, and emotional development. These attachments vary in quality, depending on how caregivers respond to the infant’s needs. When caregivers are attentive, infants are likely to develop secure attachments. However, if caregivers neglect their needs, infants may develop insecurity, leading to challenges in emotional development and difficulty in forming healthy relationships later in life.

To understand how parenting influences attachment formation and child development, researchers led by Associate Professor Atsuko Saito from the Department of Psychology at the Faculty of Human Sciences at Sophia University, and including Saori Yano-Nashimoto (RIKEN Center for Brain Science; Hokkaido University), Anna Truzzi (RIKEN Center for Brain Science; Trinity College Dublin; University of Trento), Kazutaka Shinozuka (RIKEN Center for Brain Science), and Kumi O. Kuroda (RIKEN Center for Brain Science; Tokyo Institute of Technology), studied infant attachment behaviors in common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). Their findings, published in the journal Communications Biology on February 20, 2024, reveal that infant marmosets adjust their attachment to different caregivers. However, those raised away from their families fail to develop similar adaptive mechanisms and develop attachment disorders.

Marmosets are small monkeys native to South America. They have a family structure that has a resemblance to the family structure in humans, where the father, mother, and older siblings take turns carrying the cubs on their backs. The presence of multiple caregivers makes it possible to study the effects of different parenting styles on attachment formation.

“Marmoset babies change their attachment behavior depending on their caregivers. Such relationships with families during early childhood are thought to influence the development of attachment and independence, and are expected to provide hints about the development and independence of human children,” explains Dr. Saito.

To study the interaction between infants and caregivers, the researchers observed their behavior during reunification. They placed an infant in a basket and the caregiver in an adjacent cage connected by a tunnel with a shutter. On opening the shutter, the researchers observed that infants call out for attention and prefer clinging to the backs of familiar caregivers, such as their parents. When caregivers were patient and attentive, infants stopped calling out once they were picked up. However, the infants avoided intolerant and insensitive caregivers. When picked up by rejecting caregivers, they continued to call out for attention.

However, this adaptable attachment behavior was not observed in cubs that were separated from their families in infancy and reared artificially. These cubs avoided their caregivers and tended to stay alone but continued to cry out for care. A significant difference between the two groups was that cubs raised by their families gradually decreased their calls as they grew older. In contrast, artificially reared cubs continued to cry out and seek assistance, even after the second month after birth, indicating a slower development of independence.

“These findings show that in marmosets, which have a family structure similar to humans, offspring flexibly change their attachment depending on the family’s parenting style, and that the offspring acquires the ability to become independent while being nurtured within the family,” explains Dr. Saito.

In most societies, mothers usually take on the primary caregiving role. However, the results suggest that infants can feel equally secure and form strong secure attachments with other supportive caregivers. This indicates that other family members can play an active role in caring for the child, which can ease the responsibilities placed on mothers. Additionally, the study highlights the role of families in fostering independence in infants. Infants become more independent through their interactions with the family.

The researchers are currently studying how attachment formation and experiencing attachment disorders affect brain development in marmosets. They aim to use these findings and contribute towards the improvement of parenting practices and childcare in humans.

Reference

- Title of original paper: Anxious about rejection, avoidant of neglect: Infant marmosets tune their attachment based on individual caregiver’s parenting style

- Journal: Communications Biology

- DOI: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-024-05875-6

- Authors: Saori Yano-Nashimoto1,2, Anna Truzzi1,3,4, Kazutaka Shinozuka1,13, Ayako Y. Murayama1,5,6,14, Takuma Kurachi1,7, Keiko Moriya-Ito8, Hironobu Tokuno8, Eri Miyazawa1, Gianluca Esposito 1,4, Hideyuki Okano5,6, Katsuki Nakamura9, Atsuko Saito1,10, and Kumi O. Kuroda1,11,12

- Affiliations:

1 Laboratory for Affiliative Social Behavior, RIKEN Center for Brain Science

2 Laboratory of Physiology, Department of Basic Veterinary Sciences, Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University

3 Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience, School of Psychology, Trinity College Dublin

4 Department of Psychology and Cognitive Science, University of Trento

5 Department of Physiology, Keio University School of Medicine

6 Laboratory for Marmoset Neural Architecture, RIKEN Center for Brain Science

7 Department of Agriculture, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology

8 Department of Brain & Neurosciences, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science

9 Center for the Evolutionary Origins of Human Behavior, Kyoto University

10 Department of Psychology, Sophia University

11 Kuroda Laboratory, School of Life Science and Technology, Tokyo Institute of Technology

12 Laboratory for Circuit and Behavioral Physiology, RIKEN Center for Brain Science

13 Planning, Review and Research Institute for Social insurance and Medical program

14 Neural Circuit Unit, Okinawa Institute Science and Technology Graduate University

About Associate Professor Atsuko Saito from Sophia University

Atsuko Saito graduated from The University of Tokyo’s Department of Life and Cognitive Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, and earned her Ph.D. at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. She served as an Assistant Professor and Lecturer at The University of Tokyo and subsequently, as a Lecturer at Musashino University’s Faculty of Education, before assuming her current position in 2018.

Funding information

This study received partial funding from the Sophia Institute for Human Security and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP17J07440.

Media contact

Office of Public Relations, Sophia University