Faculty of Human Sciences Professor Taro Komatsu has long been involved in efforts to restore educational opportunities in conflict-affected countries such as Bosnia, Jordan, Afghanistan, and East Timor. What is the true meaning of learning? In search of the answer, Komatsu discusses his findings on the importance of ensuring education as a means to maintain peace.

Most wars of the 21st century are ethnic conflicts. In many instances, ethnic groups on opposing sides of conflicts will continue living together in the same country even after a conflict subsides ―a situation that leaves open the possibility of subsequent armed conflict.

One of the focuses of my research is education’s role in maintaining peace; more specifically, how education can prevent the generational transmission of conflict-associated resentment.

In the 90s, a large-scale conflict between three religious ethnic groups ― Croats (Catholic), Serbs (Orthodox), and Bosniaks (Muslim) ― erupted in the country of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Southeast Europe. Following the conflict, these different ethnic groups have concentrated influence in regions where they constitute the majority of the population.

This situation resulted in slanted education programs that only offered the perspective of the ethnic majority. The students attending these schools, however, are children of diverse regional ethnic backgrounds. In light of these circumstances, what considerations have teachers offered to students attending these schools?

History education does not seek a correct answer, it seeks to bring together interpretations

One teacher in Bosnia and Herzegovina allows their students to select their own history textbooks. Some students choose textbooks written from a Croatian perspective, while others choose textbooks based in a Bosniak perspective. The writers of these respective textbooks have their own perspectives, which is reflected in their content.

So, rather than focusing on “what is correct,” students are tasked with focusing on “what is written” and exploring where and why interpretations diverge.

Schools only attended by children of a single ethnic group may encourage entrenched biases among students and teachers. This is why schools and local civic organizations cooperate to provide opportunities for different ethnic groups to interact through communal activities. These activities are extracurricular and not part of public educational programs, but the involved civic organizations are in close dialogue with school personnel.

Indeed, conflict within the country has inflicted emotional and physical scars on many teachers. What has inspired me is, that despite these scars, teachers are hopeful in their efforts to use education as a means to prevent the generational transmission of resentment.

“Once I have the baseline necessities, I want to learn!”

Another focus of my research is the question of why people in conflict-affected societies tend to be highly motivated learners. I have been conducting interview surveys with refugees to explore this question.

When one thinks of humanitarian aid, the first types of aid that probably come to mind are food, clothing, and shelter. However, if you go to a refugee camp and ask people living there what they need, many people, parents and children included, will reply with “education.” If you ask children in Japan why they want to go to school, many will say “because I want to make friends.” Meanwhile, children refugees will say “because I want to learn.”

This was the same reply I got from young people in East Timor who were unable to receive adequate education due to regional conflict. When I asked them why they want to continue their education, I expected their motivation would be driven by enhanced employment prospects, but, surprisingly, many replied with “because I want to learn” or “because I want to learn about what I don’t know.” The pursuit of knowledge is truly an essential human desire.

Meanwhile, Japan’s education policies do not yet center children. In pursuit of encouraging learning styles that befit a multicultural society, there is much to learn from the innovative initiatives taking place in post-conflict societies. I believe they can provide clues to how we can uproot the entrenched notions that “what is written in textbooks is correct” and that “education is something you only receive at school.”

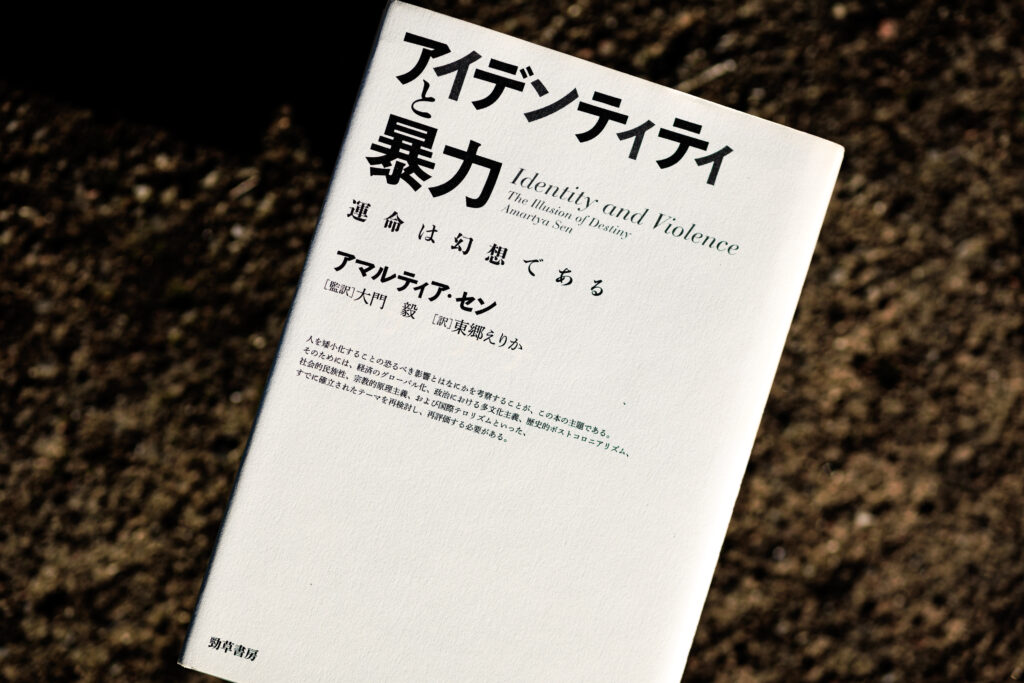

The book I recommend

“Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny”

by Amartya Sen, W.W. Norton & Company

In this work, Amartya Sen ― recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences ― discusses the upmost importance of “choice” within the context of war and conflict. The book taught me that identity is ours to choose and that it is possible for us to have multiple identities. It taught me the importance of the freedom to choose in matters that impact one’s life and existence.

-

Taro Komatsu

- Professor

Department of Education

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Professor

-

After earning his BA in Comparative Culture at Sophia, Professor Taro Komatsu earned his MSc. from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). He subsequently earned his PhD in Education Policy and Administration from the University of Minnesota. He has worked at the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Pakistan office. He also served as a program officer at UNESCO Paris Headquarters, education administrator at the UN Mission in Kosovo, and as an education officer at UNESCO Bosnia and Herzegovina. He served as Associate Professor at Kyushu University before assuming his current post in 2013.

- Department of Education

Interviewed: October 2023