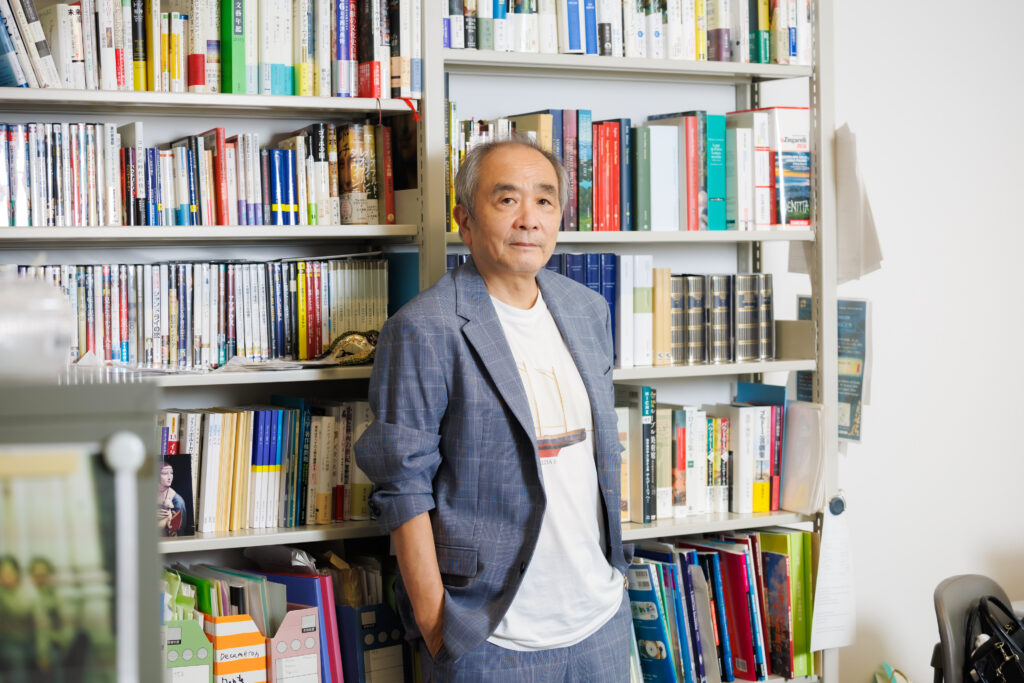

Associate Professor Yasunori Tsutsumi of the Center for Language Education and Research studies contemporary Italian literature and works as a translator. Here he speaks about the charm of the maze-like depth of Italian literature, which is less familiar than French and German literature.

Are there any books that come to mind when you hear the term “Italian literature”? Books from the Middle Ages through to the Renaissance period, such as La Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy) by Dante and Decameron by Boccaccio, are mentioned in school textbooks, but since then, it cannot be said that Italian literature has claimed high levels of attention. But that does not mean that Italian literature lacks charm. I have spent the past forty years immersed in the deep charm of Italian literature, and I continue my research in this field centered around contemporary works.

Calvino’s works were born from Italian folktales

One of the authors I research is Italo Calvino, who in 1956 published Fiabe italiane (Italian Folktales). Italy was slow to achieve national unity, and the languages spoken differed between regions. Work on collecting together folktales from throughout the nation failed to advance. Amid this, Calvino decided that he wanted to write an Italian version of the Grimm’s Fairy Tales, so he gathered together folktales from around the country, rewrote them into Italian and compiled them into a collection.

Calvino is quoted as saying that one of true essences of folktales is “humans, animals, plants, things and everything that is whole, and everything that exists within these have the potential for limitless transformation.” Humans change into animals, and animals change and transform into plants. This is the main characteristic of folktales. Calvino also portrays animals and plants symbolically in his novels. Using his folktale-centric imagination to nourish his own works and concealing the various issues that Italy faced at that time in the foundations of his works enabled him to approach relationships between humans and nature and humans and history, and that is the main charm of his works.

Translating literature is the same as researching it

I am a translator of Italian literature, but I have never thought of research and translation as separate fields. There are times when translating works into my mother tongue, Japanese, enables me to see the in-depth meaning of the original book for the first time.

To change the subject, have you ever seen a vegetable known as the artichoke? It is a green vegetable resembling a pinecone in shape, and it is commonly eaten in Italy. The Italian word for it is carciofo. At first, despite repeatedly looking it up this word, which appears regularly in Calvino’s works, in the dictionary, I could never remember it. I felt like cursing my poor memory. However, having traveled to Italy and eaten this vegetable for the first time, I was finally able to remember it. Translating literary works is no different. Although it is fine to learn languages, read books, read related research papers and discover details on the period in which the author lived, there are certain points that can only be understood for the first time when actually visiting the location depicted.

When I was translating La coscienza di Zeno (Zeno’s Conscience; published in Japanese by Iwanami Shoten in 2021), I visited Trieste, where the book is staged, and spoke with the chief of a research center that studies the author of the book, Italo Svevo. I also visited a library Svevo attended, and wandered around the lanes walked by the protagonist. The book portrays a man named Zeno who lived in this town so far from Japan, and I, living one-hundred years later, was able to feel great empathy for him. This enabled me to reacquaint myself with the greatness of Svevo, who effectively depicted the folly and absurdness of human existence.

Italy, which flourished as the center of the Roman Empire and was the birthplace of the Renaissance, has glorious scenery and delicious food. But that does not cover everything about Italy. Only 160 years have passed since the country became unified, meaning that the history and culture of the north and south differ, and its history also includes a civil war occurring at the end of World War II. Coming into contact with its literary works helps us to understand the people and society, as well as the relationships between the people and history. I believe that literature acts as a bridge for understanding different cultures.

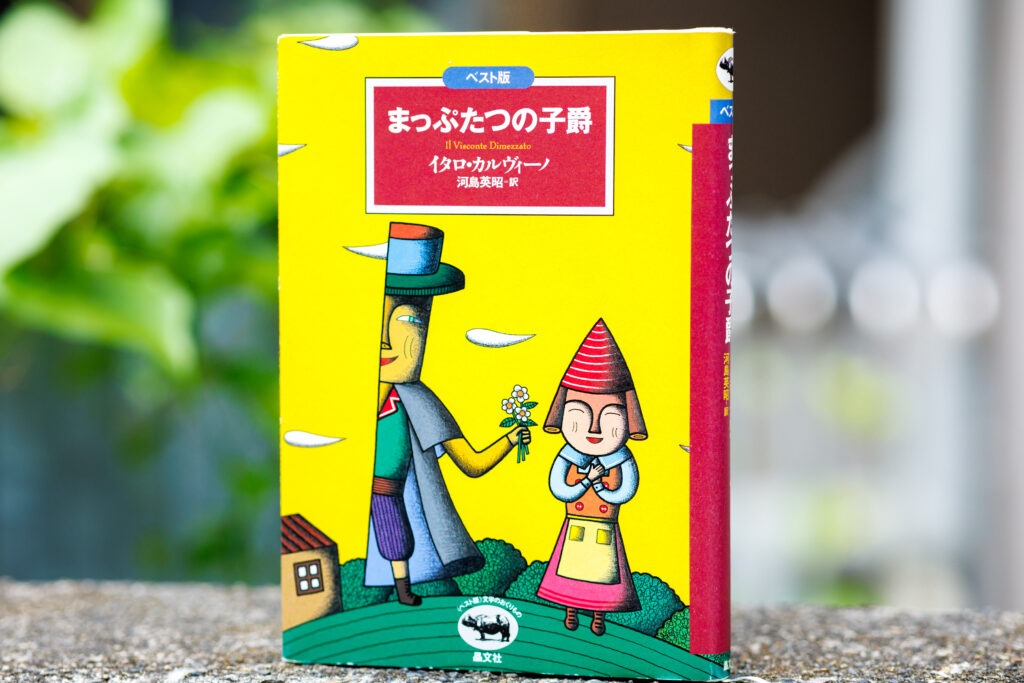

The book I recommend

“Il visconte dimezzato”(The Cloven Viscount)

by Italo Calvino, Japanese translation by Hideaki Kawashima, Shobunsha

A fable by Calvino based on Italian folklore. It tells the story of a viscount cloven into two during the war with Turkey who returns home while split into good and evil. It portrays the dichotomic character of humans, and is a story with great depth and a vivid reminder of the world during the cold war of the 1950s.

-

Yasunori Tsutsumi

- Associate Professor

Center for Language Education and Research

- Associate Professor

-

Graduated with a B.A. in Italian from the Faculty of Foreign Languages at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, and completed his M.A. at the university’s Graduate School. Was a part-time lecturer at the Sophia University Center for Language Education and Research before assuming his current position in 2019.

- Center for Language Education and Research

Interview conducted on: September 2022