Professor Marui of the Faculty of Global Studies is researching Banteay Kdei, part of the Angkor monuments, and its surrounding villages. She talks about the value of examining history through archeological research and area studies methods including oral history research.

Angkor monuments are Cambodia’s famed World Heritage site. My specialization is the archaeology of Southeast Asia, and at present, I am working on archaeological excavations of the Banteay Kdei site.

Thanks to peace negotiations by the United Nations and many other countries including Japan, the modern kingdom of Cambodia was rebuilt in 1993. Cambodia had been laid waste by long years of civil war, including the Pol Pot regime, and many different countries took part in its reconstruction. Conservation of historical Angkor sites was one of these projects, with Sophia University assembling its survey team in 1991. I joined in 1994, and have since continued my own research while providing support for cultural recovery and the training of people involved in that.

Archaeology is a vital tool for regions with little written historical documents

Archaeology is the study of historical sites, and it ranges from massive constructions such as the pyramids of Egypt to small items buried underground like pots. We use these artifacts to bring to light how people of the past lived and worked; their culture and values. Cambodia has far fewer written historical documents than Japan, so when researching its history, an archaeological approach is vital.

Banteay Kdei is believed to be a Buddhist temple constructed at the end of the 12th century. It is surrounded by an external wall 600 meters long east to west, and 480 meters long north to south. In 2000 and 2001, a total of 274 destroyed Buddhist statue pieces were found there, creating quite a stir.

I work with a team of local workers and university students. Our work basically involves digging away the earth from the top down, estimating the differences in age between artifacts based on the vertical relationship between the soil layers. It is also important to check if anything we find, like pottery shards or tile shards, can be joined together. If we can reassemble something into its original form, we can understand not just how, for example, roofs were tiled or the structure of buildings, but also the process by which the site was formed.

Distributing picture books of interviews to locals

Another research method I focus on, in addition to archaeological excavations, is conducting interviews with people living in the area. I have learned that Banteay Kdei, especially recently, has been used at times as a place of refuge from war, at other times as a gravesite to bury ancestors, and various other usages. We can say that before registration as a World Heritage site, Banteay Kdei was a historical site that was part of the lives of local people.

My other area is area studies, and here I focus on the how the world is viewed from a local perspective. Researching and presenting how local people engage with the Angkor monuments, or how they live with them, has meaning in the sense of getting more people to understand the diversity of regional cultures.

I assemble the oral folk tales about the sites that people have passed on into picture books, which I distribute to Cambodian children. In addition, I want to share with them what I have learned from archaeological excavations, so I invite local people, including children, to archaeological excavations once each one is largely complete, and talk about the findings.

In area studies, it is important to respect the history and culture of that region, and how you build relationships of trust with the locals is key. At Banteay Kdei, I do not just carry out archaeological excavations with the locals, but try to deepen mutual understanding in a range of day-to-day areas. It is this aspect, the human interactions that give me insights which academia alone cannot, that appeals to me most, and gives me the motivation to return to Cambodia.

The book I recommend

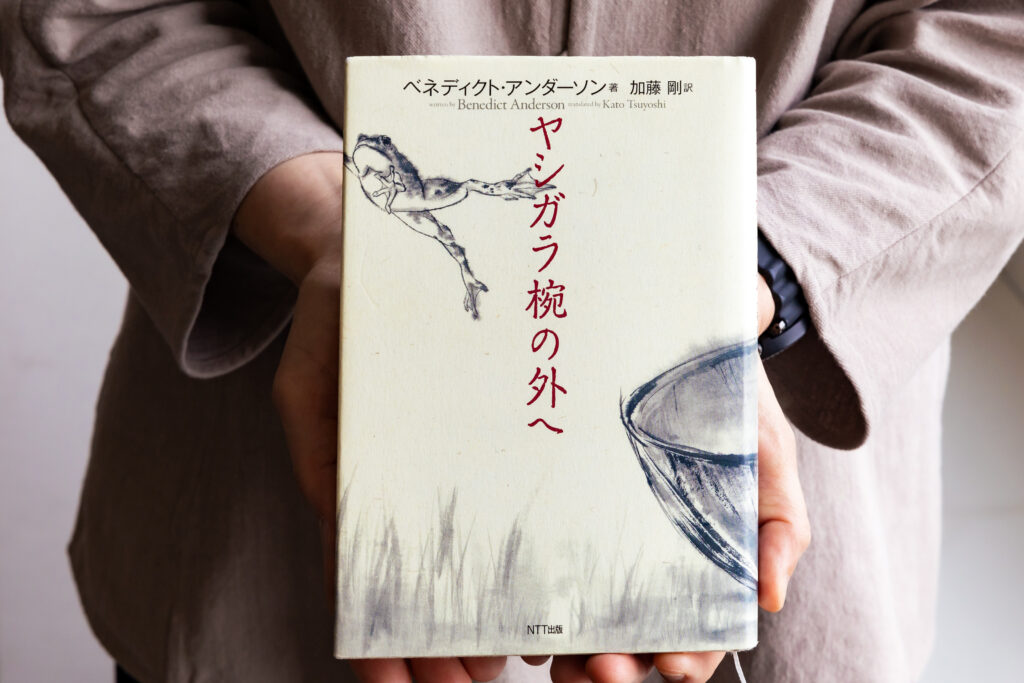

“A Life Beyond Boundaries: A Memoir”

by Benedict Anderson, translated by Tsuyoshi Kato, NTT Publishing

Written by an author known for his work in area studies for a Japanese audience, this is a memoir looking back on his own research path. Anderson passionately describes how in academia you should not be limited by university systems or your own country. You should go beyond the boundaries and not be the proverbial frog stuck under the coconut-shell bowl.

-

Masako Marui

- Professor

Department of Global Studies

Faculty of Global Studies

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of History, Faculty of Humanities at Sophia University, then withdrew from the doctoral program in Sophia’s Graduate School of Languages and Linguistics after completing the course. After a career that included working as a full-time lecturer in the Faculty of Foreign Studies at Sophia, she assumed her current post in 2014.

- Department of Global Studies

Interviewed: May 2022