Professor Toshiro Terada of the Faculty of Humanities specializes in practical philosophy. He studies the works of Kant and other modern practical philosophers, and also runs “philosophy cafes” and other activities related to philosophy for the civil society. He talks about the challenges and enjoyment of studying academic philosophy, as well as the influence that philosophy has over the world.

The 18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant philosophized so many things concerning human beings and the world around them, but is also known for his influential works on the actions of human beings, including morals, politics and law. This kind of philosophy is called “practical philosophy” and is the field of research that I focus on.

Kant advocated the idea of “cosmopolitanism,” in which human beings were supposed to be capable of acting, speaking and thinking beyond national boundaries, as long as they held reason or rationality. Cosmopolitanism is the topic that I have been focusing my efforts on particularly in recent years. While this way of thinking may be completely normal in today’s age of globalization, Kant had already developed concepts like these that were not yet common in the 18th century.

The world today is heavily influenced by Kant’s views of cosmopolitanism—even the concept of the United Nations is partly based on Kant’s ideas. Philosophical thinking has a significant impact on the way our world is, and will continue to do so in the future.

There is more to philosophy than its academic aspects

Research into academic philosophy generally consists of reading and interpreting literature related to philosophy. The first step to studying Kant’s works is learning how to read German—only then are you able to empathize with his thoughts, or otherwise question them while having a dialogue with his works.

Countless researchers have deciphered the works of Kant to date, and we need to understand these interpretations and coming up with new interpretations. Neither of these are an easy task, but such research becomes even more interesting when you develop your own way of interpreting Kant’s works.

Yet I think that simply taking an academic stance is not sufficient. Kant referred to academic philosophy as the “philosophy according to scholastic concept,” and in contrast, the way human beings with reason should view matters with a philosophical outlook as “philosophy according to world concept”. Kant stated that the latter is philosophy in the true sense, and I very much agree with his view.

Indeed, the world is abound with questions that people should be concerned with—problems of environment, human rights, war and peace, and poverty, to name a few. I believe that if people are able to think over these questions philosophically, it will contribute to transforming the society.

Philosophical discourse is based on freedom and equality

Recently I have been holding philosophy cafes or heading out with my students to elementary schools and high schools or even companies to think philosophically with people who are not familiar with philosophizing. We introduce them to methods of philosophical dialogue and invite them to keep the dialogue flowing, to overcome challenges and to change their views. This forms part of my academic research activities.

The philosophical dialogue I enjoy with people involve simple questions that people rarely think about—like what exactly is happiness, whether or not freedom is a good thing, or if good and evil is universal—and we discuss them together.

While everyone can have their own opinion about philosophical questions, they will never find any final answer. It’s no use if you ask a teacher, your parents, look up an encyclopedia, or search for it on Google. The only way to find out is to talk about the matter with other people who have the same question.

Philosophical discourse allows anyone to build a free and equal relationship—adults and children alike can contemplate matters independently and interactively. It is the ultimate way of active learning, so to speak.

The term “philosophical” does not mean giving the correct answer, but rather thinking about a particular matter. It is vital to understand the meaning of thinking about things philosophically, as well as learning the method for doing so.

If people can do this, it will form the basis for thinking about a wide range of social issues—and it will also be a useful skill for any type of work in the future. My primary goal is to build a bridge between academic philosophical research and philosophy that people can practice in their daily lives.

The book I recommend

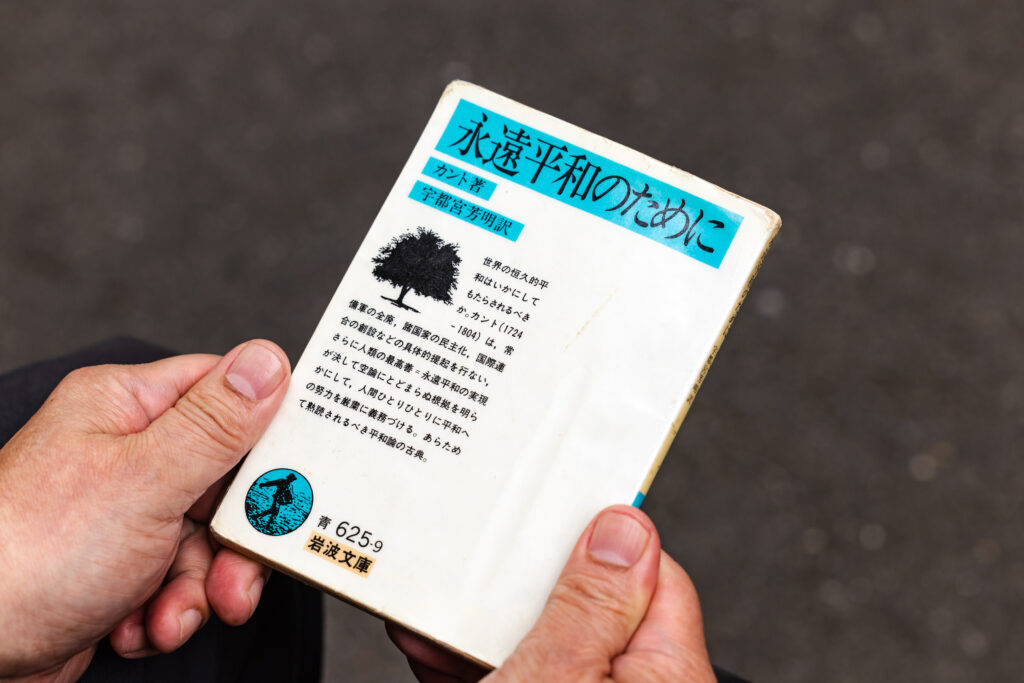

“Zum Ewigen Frieden” (Toward Perpetual Peace)

by Kant, Japanese translation by Yoshiaki Utsunomiya, Iwanami Bunko

A good guide to Kant’s practical philosophy, and recommended as the first book to read about philosophy. The book discusses war and peace, which is especially poignant today. You might not understand the content completely the first time you read it, but I would suggest reading it over again after several years—that is what books on philosophy are all about.

-

Toshiro Terada

- Professor

Department of Philosophy

Faculty of Humanities

- Professor

-

Graduated from Philosophy at the Faculty of Letters, Kyoto University, receiving his M.A. and finishing the course work for Ph.D. Later received his Ph.D. from the Graduate School of Letters, Osaka University. Taught as assistant professor in the Faculty of Liberal Arts at Meiji Gakuin University, associate professor in the Faculty of Law at the same university, and his current position from 2010.

- Department of Philosophy

Interviewed: May 2022