Music in the West developed closely in the relation to Christian prayers. The “Ave Maria” is at the heart of this tradition, as elucidated below by Naruo Yamamoto, historian of Europe during the Middle Ages and associate professor of the Faculty of Humanities.

My research focuses mainly on the music of the European medieval period, and most of the music we hear today is generated in its musical tradition and culture. For example, modern musical notation of five-line staff and many musical symbols originated in the 9th century Europe and reached its completion by the end of the 15th century.

The “Ave Maria” prayer spread robustly on the wings of imagination

My recent interest is the “Ave Maria,” which is fundamentally a prayer addressing the Virgin Mary, but was given a melody and gained popularity as a song too. The latin word “Ave” means “to greet” or “to rejoice.” It was used in the Bible for announcing and blessing Mary who conceived a son to be called Jesus.

In the medieval period, other phrases (“pray for us”, etc.) were added, and the Ave Maria it became a prayer for seeking the communication and the intercession with Mary.

In general, prayer has a formula which one must follow. However, oddly, many variations were allowed for the lyrics and melody of the Ave Maria. Thus, people could let their imaginations take flight, change the words freely, put them to music, and recite by themselves. As a result, the Ave Maria spread from monasteries to cities and even to rural villages, and became an essential daily prayer for medieval people.

In that era it was customary to recite the Ave Maria many times daily: 150 times each in the morning and evening. The rosary, a physical string of knots or beads with a cross, was created to count how many times the user had recited the prayer.

Other songs about the Virgin Mary were also created in various areas, and passed down to us today. The people of the Western medieval world were enveloped in this “music of Mary”, and lived their daily lives in communion with this saint.

Feeling the emotions behind the medieval music

Mary was one of the most revered religious figures of medieval Europe and featured in various areas including paintings, sculpture, architecture, literature, and music. So, my viewpoint of the “music of Mary” could be full of possibilities for a new perspective of the Middle Ages.

I am also interested in the functions and roles that the music had in medieval Europe. They were very different from those of modern times. In our world, “visual” is often given the utmost importance, as we perceive words, numbers, geographical sphere, times, and even music by sight.

In contrast, the medieval period was one in which all five senses were equally valued. Music was not only a sort of entertainment, but also one of the most important tools for emotional communication. For example, important words were represented through the elongated and melismatic tones. The descending phrases describe sad events or sentiments.

Medieval melodies are somewhat monotonous for our modern ears, but they were of great significance for medieval communications.

Studying history is a way to understand the feelings of people in the past. Looking at the remaining musical scores and the some symbols attached to the words, I viscerally experience the world of the medieval music.

The book I recommend

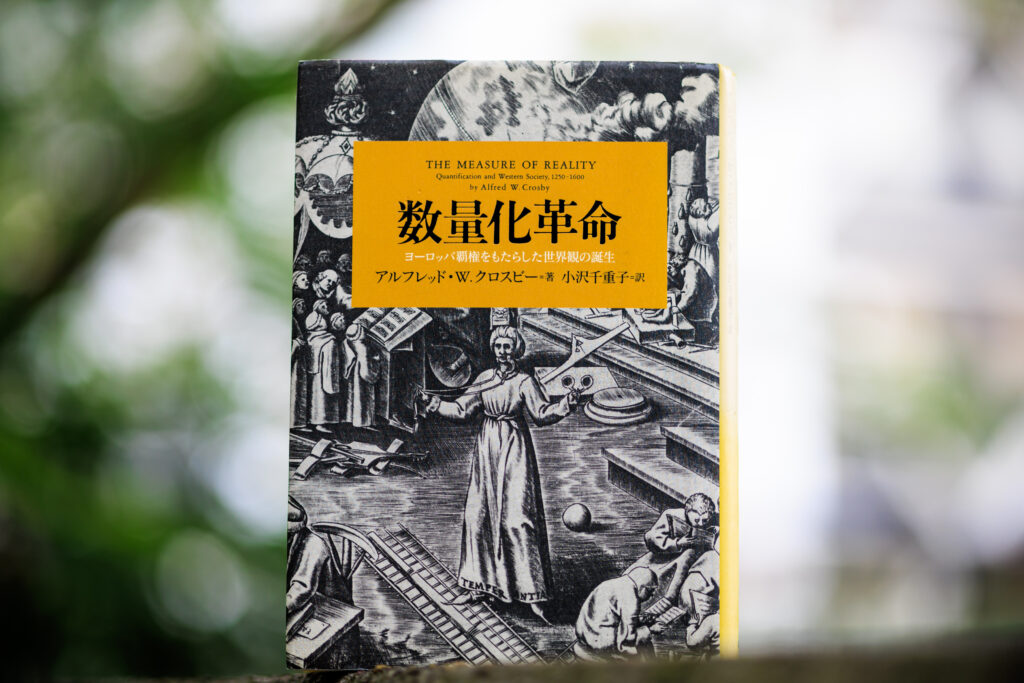

“The Measure of Reality”

by Alfred W. Crosby, Japanese translation by Chieko Ozawa, Books Kinokuniya

The author attributes the global dominance of European values from the Age of Discovery onward to the quantification revolution of the medieval period, characterized by the invention of clocks, Arabic numerals, accurate maps, and the like. It provides an intriguing perspective on world history by asking the big questions.

-

Naruo Yamamoto

- Associate Professor

Department of History

Faculty of Humanities

- Associate Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of History, Faculty of Letters at Gakushuin University, and received his M.S. at the Centre d’Études Supérieures de la Renaissance at the Université de Tours, and his Ph.D. in Letters at the Department of Occidental History, European and American Studies, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology and Faculty of Letters, The University of Tokyo. After serving as an associate professor at Showa Women’s University, was appointed to his current position in 2022.

- Department of History

Interviewed: July 2023