Professor Toshihiro Okuyama of the Faculty of Humanities draws on his experience as a newspaper reporter in his research into various issues facing Japanese journalism today, such as ongoing evolution of the Whistleblower Protection Act of Japan, should-be freedom of access to public information, and the possibility of non-profit news organizations in Japan.

I worked at The Asahi Shimbun newspaper for 33 years. During my time there, I was lucky to have many opportunities to consider what our journalism should be, and this has motivated my research both into the legal frameworks that protect whistleblowers, and into the actual application of them.

In investigative journalism where reporters find something newsworthy, carry out their own investigations and publish what they have learned with their own responsibility, whistleblowers are often very important sources of information. Because whistleblowers benefit society and the public, it is vital that we protect them and ensure that any harm they incur is minimized.

This idea has now become established in Japan at least in public posture: the Whistleblower Protection Act came into force in 2006, and drastic amendments were issued in 2020. But it is far from enough. The structure of the Act is complex, and its scope is narrow. Some whistleblowers are not protected by this law. Evidently, huge issues remain.

The importance of maintaining the quality and volume of the flow of public information

One of my greatest concerns is that public distrust in the Japanese press has increased in recent years. An abundance of information is available, both good and bad. However, it requires both hard work and financial investment to uncover crucial information that ought to be known by the public, and the risks are high for reporters and news organizations to do this kind of investigative reporting. But it is not easy to let the public be aware of these facts.

Let us take the Fukushima nuclear disaster as an example.

Overseas media outlets including leading U.S. newspapers published misleading reports about the terrifying situation of spent fuel pools based on the United States government’s erroneous announcement. The New York Times quoted some dire comments of the U.S. official who said that there was no water in one of the pools and that workers were going to be unable to be at the plant due to too high radiation levels.

These reports were read through the internet by some Japanese, who then condemned the domestic press for not reporting these comments enough. As a result, a large section of the Japanese public lost trust in the domestic press.

The fact was that there was enough water in spent fuel pools in Fukushima. What the U.S. official said at that time was not true. Of course, it takes much more effort to investigate, to verify and to refute unjustified criticism than to come up with such criticisms.

As distrust in the press has grown, so the social and legal environment surrounding news gathering and reporting activities has deteriorated, possibly leading to a situation in which reporters and news media could no longer communicate enough information that is necessary to the public. This is incredibly alarming. As a democratic society, it is imperative we maintain the quality and volume of the flow of information that is necessary to the public.

The future of the press

Going forward, I believe the press must as plainly as possible show the public what it does, and what concerns it has. News media should reveal what reporters are discussing, worrying and dodging.

I also keep a close eye on non-profit news organizations. Since my time at The Asahi Shimbun, I have been a member of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a non-profit news organization headquartered in the U.S., and I have collaborated with reporters and news organizations from various countries on various projects including the Panama Papers, the Paradise Papers, and Offshore Leaks. If such collaborations become the norm, then we should be able to enjoy a freer and more diverse form of reporting.

I hope to contribute to introducing some kinds of systems that make it easier for non-profit news organizations to make their ends meet with donations, and to creating strategies to ensure the continued survival of investigative journalism.

Whatever happens, it is vital that the truth prevails—this holds both for journalists and for scholars. We must, as far as possible, rid ourselves of preconceptions and bias; we must shine a light on the truth from multiple angles, from various viewpoints, and with as much objectivity and as much courage as possible.

In my research, I hope to think things through in such my own manner, in the same way I did when I was a newspaper reporter.

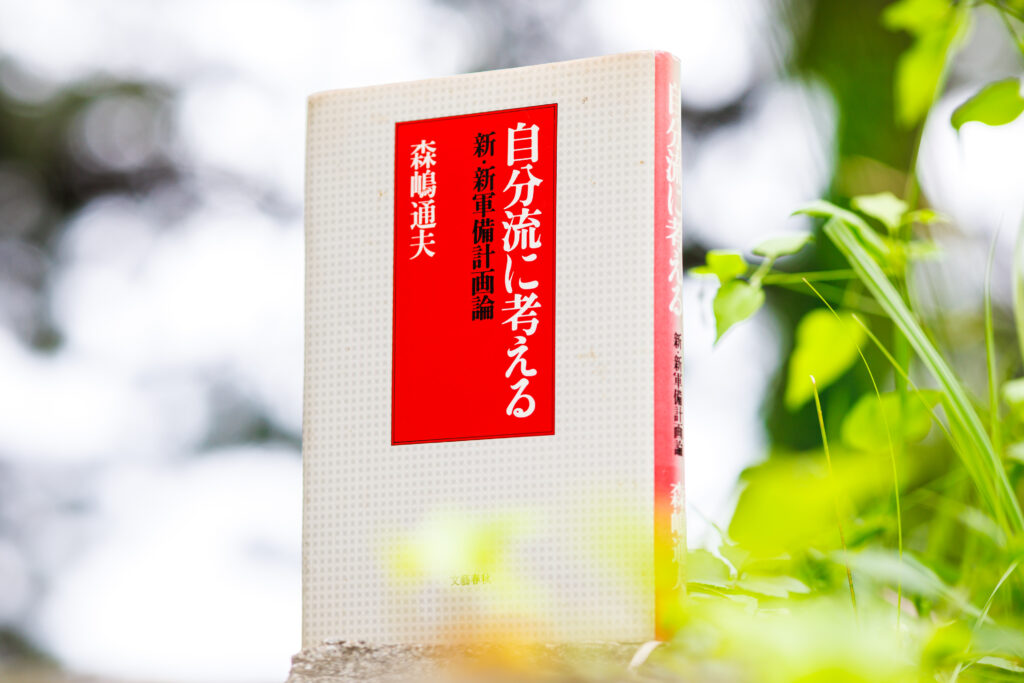

The book I recommend

“Jibunryu ni kangaeru shin-shin-gunbi keikakuron” (Thinking in one’s own unique way: a new, new national security planning)

by Michio Morishima, Bungeishunju

I read this book on the recommendation of a graduate student who was helping me at a seminar of the college. It explains how we can free ourselves from conventional notions and give shape to new ideas. Since reading this book, I have taken care to think things in my own unique way.

-

Toshihiro Okuyama

- Professor

Department of Journalism

Faculty of Humanities

- Professor

-

Professor Toshihiro Okuyama graduated from the Department of Nuclear Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, the University of Tokyo and also completed the prescribed course of Undergraduate Research Student at the university’s Institute of Journalism and Communication Studies in 1989. After joining The Asahi Shimbun, Okuyama reported from the organization’s Mito bureau, Fukushima bureau, Shakai-bu, and Investigative Reporting Team, and became a Senior Staff Writer in 2013. Okuyama won the Shiba Ryotaro Prize and the Japan National Press Club Prize in 2018 for his book, Himitsu kaijo Lockheed jiken (Declassification of the Lockheed Scandal). He was appointed to his current position in 2022.

- Department of Journalism

Interviewed: August 2022