Professor Katsutaka Hojo of the Faculty of Humanities specializes in history and researches public history. Making use of his fieldwork, he hopes to change the history shared with society to make it more just and publicly available.

I am engaged in research into the relationships between humans and the natural environment within the wide area of eastern Eurasia. I originally focused only on ancient documents for my studies, but I have gradually begun to rely more on fieldwork.

I am recently engaged in public history, a discipline where history is compiled through joint research with the general public, rather than being monopolized by experts, with the aim to bring it closer to a truer and fairer representation of history. I want to help our shared history be more connected to the public, while also being conscious of representing minorities within that history.

The theme that I am currently researching is fur farming, which contributed to the modernization of Japan. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, the trading of fur in the northern territories of Japan involved hunting for sables, silver and black foxes, beavers, and other such animals, but having entered the 20th century, fox farming was started as an alternative to hunting. The fur of silver and black foxes fetched high prices, which resulted in the acquisition of foreign currencies.

Foxes are very nervous creatures and are not conventionally suited to farming, but breeding techniques were established in Canada and Alaska, and these were introduced to Japan. High temperatures led to the spread of parasites and pathogenic bacteria, so the areas that flourished were colder and dryer regions, such as Sakhalin, Hokkaido, Karuizawa and Nagano. Tanuki racoon dogs and weasels were also targeted for farming due to an expanded military presence in the northern regions, and ordinary households and schools were encouraged to breed rabbits. Rabbits were easily bred and easily reared, and they could also be used for food. This reflects the education of the time which expounded the importance of serving your country. Schools that raise rabbits are common even today, although the reason for this is largely forgotten.

Acquiring information from a generation of children whose parents bred fur animals

However, once the war situation worsened and it was no longer possible to export fur, fur farming began to go into decline throughout Japan and mostly disappeared in the aftermath of the war. For some reason, there are no research archives remaining, and no mention of this in the archives of local governments. I began searching for documentation, and during the process of trial and error, I experienced an encounter in Takizawa, Iwate Prefecture.

A fur farming facility was established in this area in 1937 under the direct jurisdiction of the former Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and bred high-quality tanuki racoon dogs and weasels for war supplies, and to revitalize the northeastern region of the country. Despite the fact that this was a leading organization, so to speak, there were no concrete details to be found anywhere. However, the generation of children whose parents worked for this facility remembered certain points or knew certain details from what their parents had told them. I interviewed these people and began to understand the state of this facility that supplied animal resources to the total war system.

Increasing options to produce fair and just history

A heightened awareness of animal welfare is currently spreading throughout the world, and the use of real fur is a target for criticism. In the same way, there is an increasing number of voices in Japan criticizing Russia and China, which are major production bases, but fur farming was also booming in Japan before the war. There is a lack of fairness and justice with regard to this situation, so we need to correct the level of justness and do everything within our power to consider the problems involved from the same perspective.

In the society in which we live, there is sometimes a tendency for large numbers of people to forget matters of which they were previously fully aware, giving rise to a phenomenon known as “collective amnesia”. The way in which history is viewed by the media and the government also becomes distorted, and this information can often become widespread. What we need now is to go back and look at our forgotten history to give more options and perspectives to the general public when discussing these and other issues. In addition to the history of systematically farming animals for their fur, this also applies to the history of women and sexual minorities, as well as the history of the Ainu people, Okinawa and other such matters. I personally believe that this represents the starting line for us to realize justness in history.

The book I recommend

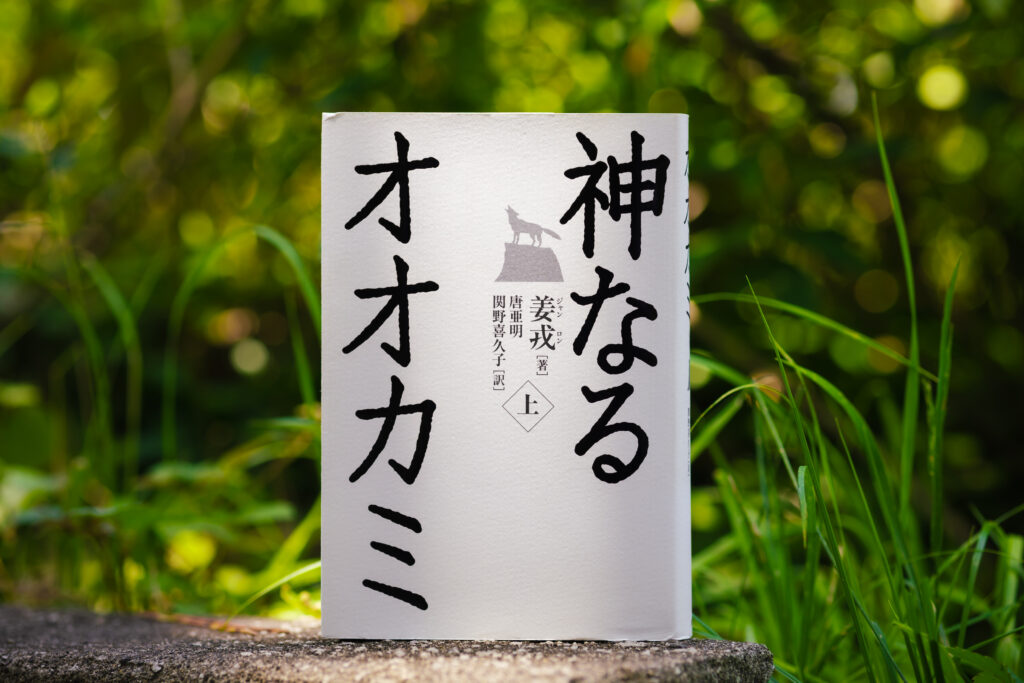

“Wolf Totem” (The Wolf Who Became a God)

by Jiang Rong, Japanese translation by Tang Yaming and Kikuko Sekino, Kodansha Ltd.

An experience-based novel about a young man dispatched to Mongol during China’s Cultural Revolution. The story portrays the protagonist who, while living among the Monglians, realizes that the Han Chinese history and culture he had been taught was all wrong, and discovers a new viewpoint of history and way to view the world.

-

Katsutaka Hojo

- Professor

Department of History

Faculty of Humanities

- Professor

-

Withdrew with full credits after completing a doctoral course in history at the Graduate School of Humanities, Sophia University, and received his MA in history. Joined Sophia University in 2006 after working as a part-time lecturer at Japan Women’s University, Saitama Gakuen University, Waseda University and other schools, and assumed his current position in 2019. Director of the Sophia Archives since 2020.

- Department of History

Interviewed: June 2022