Professor Tadashi Anno of the Faculty of Liberal Arts studies national identity—people’s beliefs about the characteristics and roles of their country—in relation to foreign policy and changes in the international order. How do national identities shape international politics?

In international relations, we often hear individuals talk about their country as having distinctive characteristics, attributes, roles, or place in the world. Such a belief held by individuals about their country’s characteristics and roles is known as “national identity.” The desire for self-esteem is deeply ingrained in human nature, so we tend to seek as positive an image of our country as possible. This can influence policy and may sometimes cause international conflicts. My research examines the relationship between national identity and foreign policy in the context of changes in the international order. In particular, my work has focused on the cases of Russia and Japan.

My interest in this subject goes back to my undergraduate years, when I was studying about the Russian Revolution. The Russian Revolution is generally thought to have resulted from popular discontent with Russian autocracy, intensified by the food shortages during World War One. However, I came across a book which advanced an entirely different interpretation: Essentially, Russia, which had failed to catch up with the West despite its policy of Westernization since the 18th century, sought to cast aside its sense of inferiority and satisfy its national pride by denouncing the West through the espousal of “socialism.” For me the book was an eye-opener. It also made me realize that Japan’s experience since the Meiji era bore similarity to that of Russia.

Japan’s national identity and its relationship with China

This discovery led me to conduct a comparative study of Japanese and Russian national identities. The results showed that although the two countries exhibited certain similarities in seeking to protect national pride in the face of Western influence, the ways in which they dealt with their situations differed. Strongly influenced by China, Japan compared itself to both the West and Asia, forming a new identity along the lines of, “We may not be a match for the West, but we’re number one in the non-Western world.” By contrast, Russia was primarily influenced by the Byzantine Empire, which had fallen in 1453. As a result, modern Russians sought to assert Russia’s superiority within a dyadic context that pitted Russia against the West, choosing the path of socialism in the 20th century. The conflict between Russia and the West continues to this day.

National identity is also closely related to the shape of the international order. Great powers seek to establish the rules and norms of the international society by projecting outward their own national identities. Weaker states define their identities in ways that conform with, or oppose, the existing international order. International order is shaped by competition among states to define its rules and norms, and to occupy leading positions in it. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the US-China confrontation also emerged out of this global tug-of-war, and, I believe, cannot be understood without understanding national identity.

Putting together a jigsaw puzzle from random pieces

Some have argued that as technology developed and global mobility increased, national identity would disappear, and countries and borders would lose their meaning. But as things stand, this is not the case. Is this simply because people are trapped in a narrow mindset? There is a lack of understanding regarding the meaning behind the existence of states and interstate borders. This is also something I would like to study in the future.

My research entails examining countless sources in search of relevant information, following my instincts as I repeatedly check and connect the pieces, like attempting a jigsaw puzzle which may not be solvable. It does not always go well, but when the pieces connect and you see the bigger picture, the feeling is exhilarating. Although my research is not immediately applicable to the real world of politics, I am encouraged when my work is recognized by researchers in the same field. I would be happier still if, in the longer run, my work proves useful to others as well.

The book I recommend

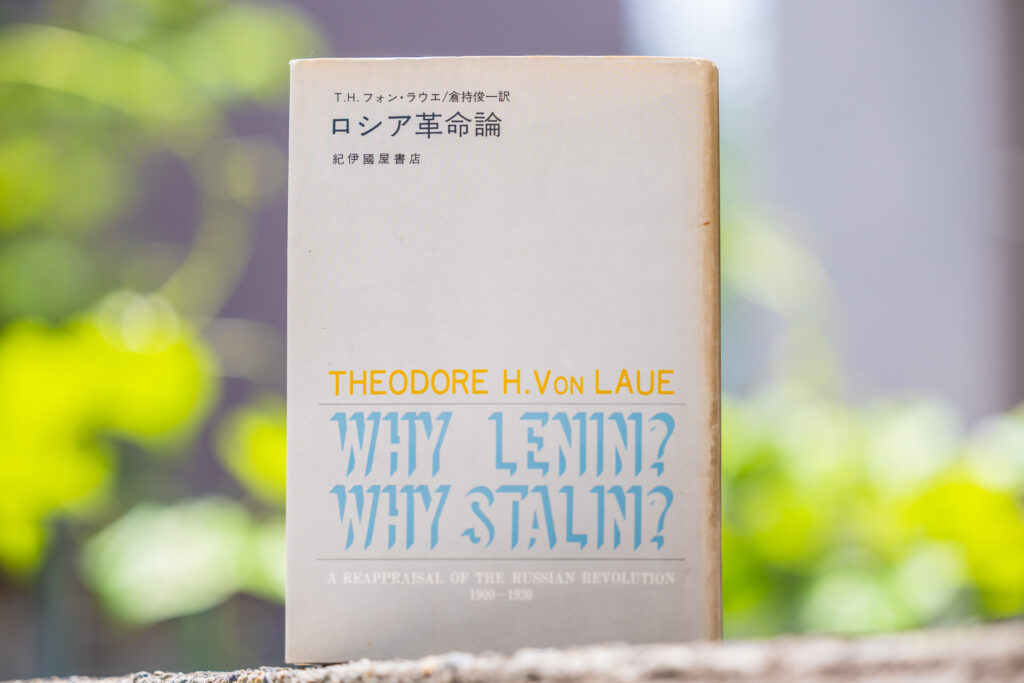

“Why Lenin? Why Stalin? A Reappraisal of the Russian Revolution”

by Theodore H. Von Laue; Japanese translation by Shun’ichi Kuramochi, Books Kinokuniya

An eye-opening work on the Russian Revolution. The book was recommended to me by a professor of Soviet economy during my senior year of college, when I was looking for a broader historical perspective. Visiting the author in a small town in Massachusetts as a graduate student is one of my fondest memories.

-

Tadashi Anno

- Professor

Department of Liberal Arts

Faculty of Liberal Arts

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Division of International Relations, College of Arts and Sciences, the University of Tokyo. Withdrew from the master’s program of the same department. Completed a doctorate in the Department of Political Science, University of California, Berkeley. Worked as a full-time lecturer and assistant professor in the Department of Comparative Culture, Faculty of Comparative Culture, Sophia University and as an assistant professor in the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Sophia University, before assuming current post in 2019.

- Department of Liberal Arts

Interviewed: June 2022