Professor Mitsuyo Sakamoto of the Department of English Studies is researching how Japanese immigrants and those of Japanese descent have maintained their Japanese language ability. How do people pass on their mother tongue to subsequent generations? Sakamoto discusses the social and interpersonal conditions needed to facilitate heritage language maintenance.

I am researching how Japanese language ability is passed down by those living outside Japan from the perspective of an applied linguistics scholar specializing in bilingual education. My experiences growing up in Canada as a child in a Japanese-English bilingual environment and living there for more than 30 years inspired my interest in this topic.

It is not easy to ensure Japanese language maintenance outside Japan. In fact, interviews I conducted with Japanese immigrants in Canada revealed that most Japanese language abilities are often lost by the third generation.

My current conclusion is that, in Canada and other parts of North America, regardless of whether parents proactively teach Japanese to their children, ensuring the transmission of language abilities remains a significant challenge without opportunities to interact with Japanese speakers.

With that said, similar interviews conducted in Brazil revealed that many individuals of third-generation Japanese descent and beyond can speak Japanese fluently. What is the reason behind this regional difference?

Elucidating the social factors that facilitate language maintenance

One factor differentiating Brazil from Canada is the number and size of Japanese communities. Japanese culture as a whole – including language and annual events – is very much part of the lifestyles of these communities. It is this environment, I suspect, that contributes to fruitful language acquisition.

During my fieldwork in Brazil, one individual expressed that if their official language had been English and not Portuguese, they might have lost their Japanese. This testimony suggests the possibility of a greater social incentive to learn Japanese in non-English-speaking countries than in English-speaking countries. I intend to continue my investigation and analysis to uncover findings that contribute to this theory.

In 2023 I commenced new fieldwork in Australia, through which I plan to focus on how schools teach Japanese as a foreign language. Alongside these findings, I would like to further explore the social factors that influence language maintenance.

Learning with those who have also lived abroad helped alleviate my “English inferiority complex”

As way to apply this research, I am interested in the interactions that arise when students who have grown up living abroad learn together with students who only grew up in Japan. Fortunately, many Sophia students have spent a portion of their childhoods abroad while many others have lived in Japan.

In my classes, I proactively create opportunities, such as group work and diary exchanges, for students from both backgrounds to interact with each other. Interviews conducted with these students revealed that this approach helped both types of students overcome their sense of language-related inferiority.

People need to interact with the external world in order to learn something new. This is especially true for language learning. We are able to learn new things only when we are able to connect our knowledge and experiences to people, stimuli, and information in the world around us. I believe that my current role is to create such opportunities for effective interactive learning.

The book I recommend

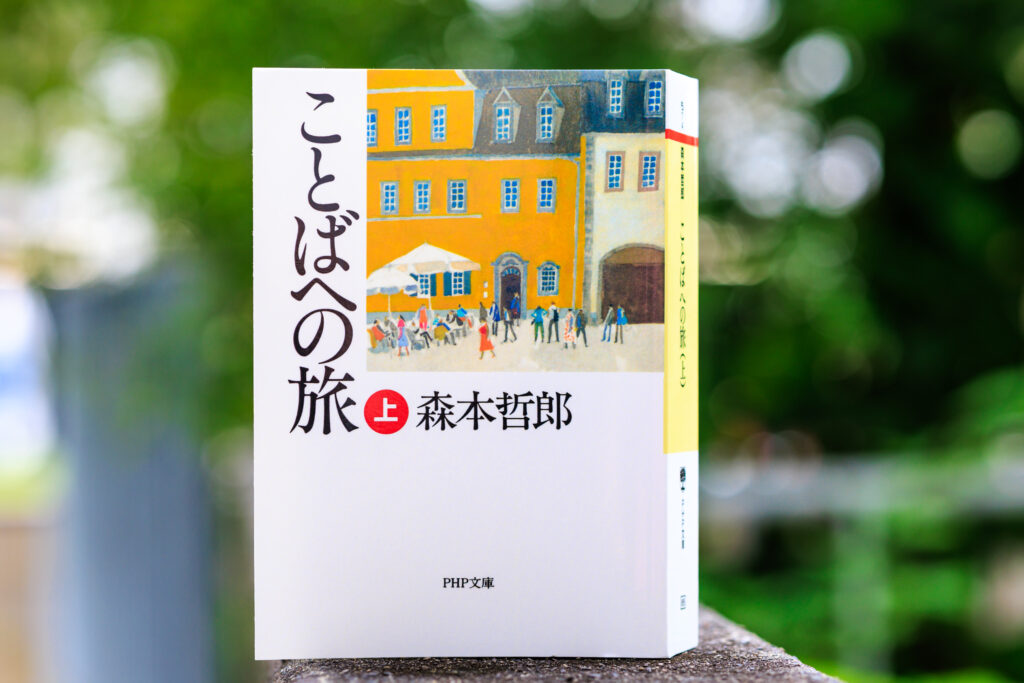

“Kotoba e no Tabi” (The Journey to Language)

by Tetsuro Morimoto, PHP Institute

This is a collection of essays that includes short commentaries on famous sayings from different eras and cultures. I read this book repeatedly as a teenager in Canada. It taught me the joy of intellectual inquiry.

-

Mitsuyo Sakamoto

- Professor

Department of English Studies

Faculty of Foreign Studies

- Professor

-

Mitsuyo Sakamoto obtained her BA in French and German language and literatures, BEd Med and Ph.D. from the University of Toronto’s Fawlty of Education respectively. Her PhD is in applied linguistics. After serving as Assistant Professor at the University of Western Ontario (now Western University), she served as Associate Professor at Sophia’s Faculty of Foreign Studies, Department of English Studies, before assuming her current position in 2012.

- Department of English Studies

Interview: June 2023