Spanish is used in many countries around the world, and is also recognized as an official language of the United Nations. Captivated by the protean world of languages—which changes according to region, speaker, and age—Professor Kimiyo Nishimura of the Faculty of Foreign Studies approaches Spanish from a linguistics perspective.

I teach Spanish to my students as a tool, but my research considers Spanish from a linguistics perspective to answer the question: what sort of language is Spanish?

When I started learning Spanish, I enjoyed the puzzle of deciphering the rules and constructing sentences. As my understanding improved, I realized there were many aspects that were not explained in our classes, or that I could not fully comprehend even after consulting reference books.

Around this time, my overseas study began in León, a small town in north-western Spain. Being exposed to living and breathing Spanish crystallized my resolve to continue researching Spanish forever.

“Diminutives” reflect the emotions of the speaker

There are many Spanish-speaking countries around the world, and there are regional differences in the Spanish spoken in each. In Latin America, for example, they continue to use older forms of Spanish that are considered archaic in Spain; Latin American Spanish has also evolved in its own, unique manner due to contact with indigenous languages.

This astounding diversity is one of the most interesting things about Spanish—and while these differences are sometimes thought of as something negative for being “nonstandard”, in linguistics we seek to observe and analyze this diversity from an objective point of view.

For my first research theme, I focused on a type of suffix known as a “diminutive.” Let me give you an example. The word “libro” means “book” in Spanish, but by adding the diminutive “-ito” we can create the word “librito,” which literally means “small book.”

But the use of this diminutive can also reflect the attitude and emotion of the speaker toward the book. In one context, it might mean something along the lines of “despite being small, it’s a book I have read numerous times and am fond of”; or, in another context, it might mean “an unimportant and boring book.”

During my time in León, I noticed that diminutives were frequently used by native speakers—and this is why I decided to incorporate them into my research. I carried out questionnaires for a variety of situations, categorizing respondents according to age, gender, etc., and I came to see a wide range of trends.

As an example, let me take the sentence: “A piece of thread is stuck to your clothing.” I investigated how people used diminutives with the Spanish word for “thread,” and it turned out that female speakers used diminutives more frequently than male speakers—although it was situation dependent.

Diminutives are fascinating: they are used differently depending on region and the gender of the speaker; they tend to be used when adults talk to children. There are various sociolinguistic differences.

Machine translation and learning Spanish

At present, my research is focused on two areas: the first is a field called morphology, which seeks to understand how new words are created; the second is describing grammatical phenomena.

Recently, I have developed an interest in the changes influenced by a heightened gender awareness. Noun endings in Spanish differ depending on whether the noun is masculine or feminine. However, some speakers are uncomfortable using these gendered nouns to refer either to themselves or to other people; other speakers are dissatisfied with grammatical rules that allow masculine forms to be used when including female persons.

In Japanese, too, we are seeing an increased awareness of the interplay between language and gender, such as in the use of the words “actor” and “actress.”

Going forward, no matter how much the accuracy of AI or machine translation improves, we will need humans who can recognize when a translation is inappropriate. I strive to be someone who can spot such instances, and I also want to nurture students who can point out with confidence when something is problematic.

When talking to someone, it is important to try and speak in their language even if you are not proficient. This might sound like hyperbole, but I believe that conversing directly in each other’s languages also contributes to world peace.

The book I recommend

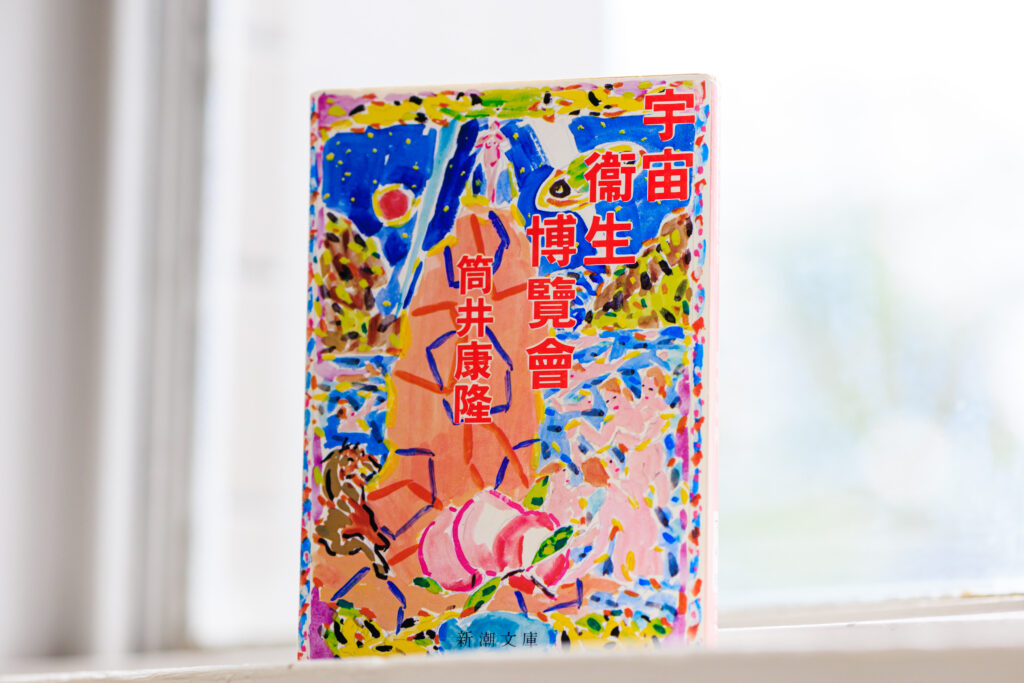

“Uchu Eisei Hakurankai”(Universal Hygiene Expo)

by Yasutaka Tsutsui, Shinchobunko

A collection of comic short stories by Yasutaka Tsutsui. I especially recommend “Kansetsu waho”—the title is a play on words that means both “indirect speech” and “speech using the joints,” and tells of aliens who communicate by cracking knuckles and other joints. The idea of using “cracks” instead of vocalisations made me terribly excited: this is linguistics!

-

Kimiyo Nishimura

- Professor

Department of Hispanic Studies

Faculty of Foreign Studies

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of Hispanic Studies, Faculty of Foreign Studies, Osaka University of Foreign Studies, and received her Ph.D. in Languages and Society from the university’s Graduate School of Faculty of Language and Society Studies. After working as a full-time lecturer then associate professor in the Department of Hispanic Studies, Faculty of Foreign Studies, Sophia University, Nishimura was appointed to her current position in 2016.

- Department of Hispanic Studies

Interviewed: June 2022