What is the difference between our modern concept of the state and that of 500 years ago? How did the monarchy then rule their vast states? Professor Shunta Uchimura from the Faculty of Foreign Studies talks about the charms of history research involving the latest knowledge related to early modern Spain and its sovereigns.

I specialize in the history of 16th century Spain, focusing on research related to the state system back then. Early modern Europe is said to be the era that gave birth to the sovereign state.

The small kingdoms of the Middle Ages became countries such as Spain and England through repeated wars, bringing about an era of absolute monarchy—I think there are many people who were taught this in school. However, kings back then did not rule the entire state with absolute power. Our concept of the modern state arose only within the past 200 years or so.

Ruling in an era without telephones, television, or internet

At that time, wars frequently broke out between the small states in Europe, but they did not always defeat and conquer their enemies through force. There were times when wars were ended through the signing of peace treaties and marriage between royal families.

As the family tree grew with each war, sometimes, when the royal family of State A died out, the ruler of State B would concurrently serve as its sovereign. However, the nobility and wealthy merchants of State A continued to hold onto power, resulting in a situation where several small kingdoms existed within one state. The monarch ruled by maintaining a balance between them.

This was the same for Spain. Although it was unified in the 16th century, small kingdoms remained. Furthermore, through marriage, Charles I from the House of Habsburg—who was born and raised in the Low Countries (equivalent to the three countries of the Benelux today)—came to rule Spain.

A king who did not know Spanish, Charles I toured the small kingdoms within his territory and continued to meet directly and communicate with local people of influence. The possibility of war and rebellion grew as his territory expanded, and there was a need for these people to provide soldiers when the time came. According to calculations, he was on the move for about one day out of every four days. Being a king was no easy task in those days.

In the 17th century, France’s Louis XIV ruled from the Palace of Versailles using written orders, but prior to him, in the second half of the 16th century, Charles I’s son Philip II issued written orders from his palace in Madrid. This drew strong resistance from all over the land and became the cause of rebellions in various parts of Spain in the 17th century.

In this way, the system of the state changes with the times and cannot be simply judged using modern standards.

Unexpected discoveries in the meticulous process of historical documental research

I am also studying the 16th century history of Toledo, an ancient city in Spain. There are extremely few documents about daily life back then, and I continue to work meticulously, much like looking through minutes of meetings which vary little in content.

However, there are also unexpected discoveries in this process. For example, I examined records about an episode where the relic of a saint worshipped in Toledo back then was found in Belgium and returned to Toledo through Philip II’s arrangements. The king did his best to meet the request of the provincial Toledo. As mentioned earlier and demonstrated by this episode, it was important for the sovereign to listen to requests from local people of influence.

I feel that such moments—when research on the local history of cities is linked to research related to the history of state systems—are also the charms of historical research.

The book I recommend

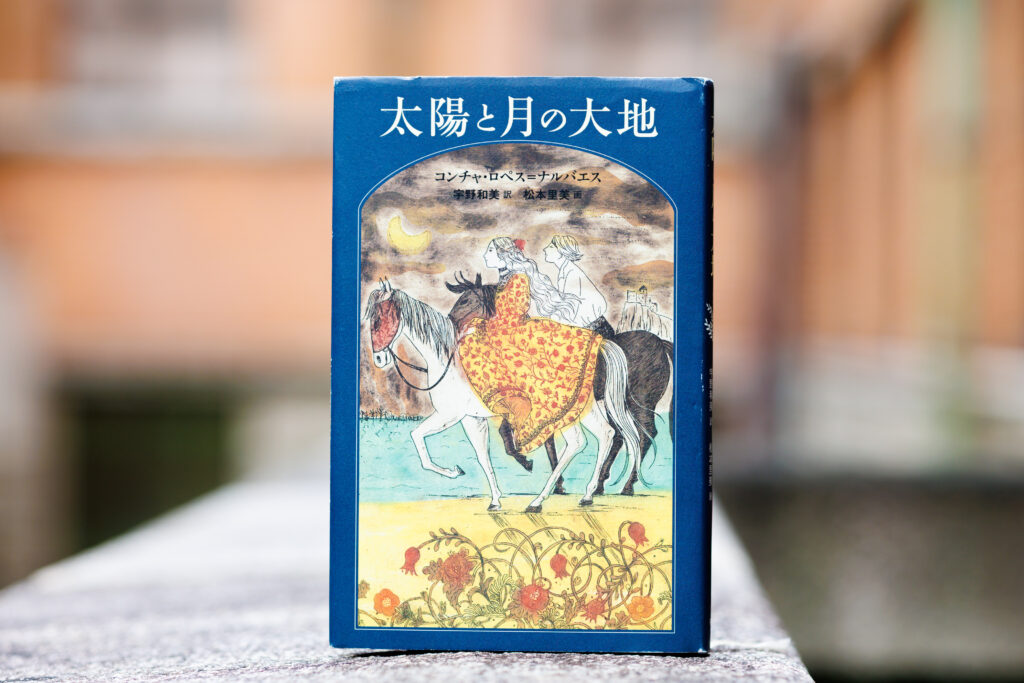

“La tierra del Sol y la Luna”(The Land of the Sun and the Moon)

by Concha López Narváez, Japanese translation by Kazumi Uno, Fukuinkan Shoten Publishers

In the 16th century, there were many Muslims in Spain who were pressured to switch religion to Christianity following the Reconquista (campaign to recapture territory). This is a children’s book that describes their tragedy. I regularly reread this book to turn my thoughts toward the unnamed people who existed in the past.

-

Shunta Uchimura

- Professor

Department of Hispanic Studies

Faculty of Foreign Studies

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Faculty of Law and Literature, Shimane University and completed the Master’s program of the university’s Graduate School of Human and Social Sciences. Received his Ph.D. after completing the Doctoral program of the Graduate School of Area and Culture Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. Assumed his current position after taking on the positions of assistant professor and associate professor at the Faculty of Foreign Studies, Sophia University.

- Department of Hispanic Studies

Interviewed: September 2023