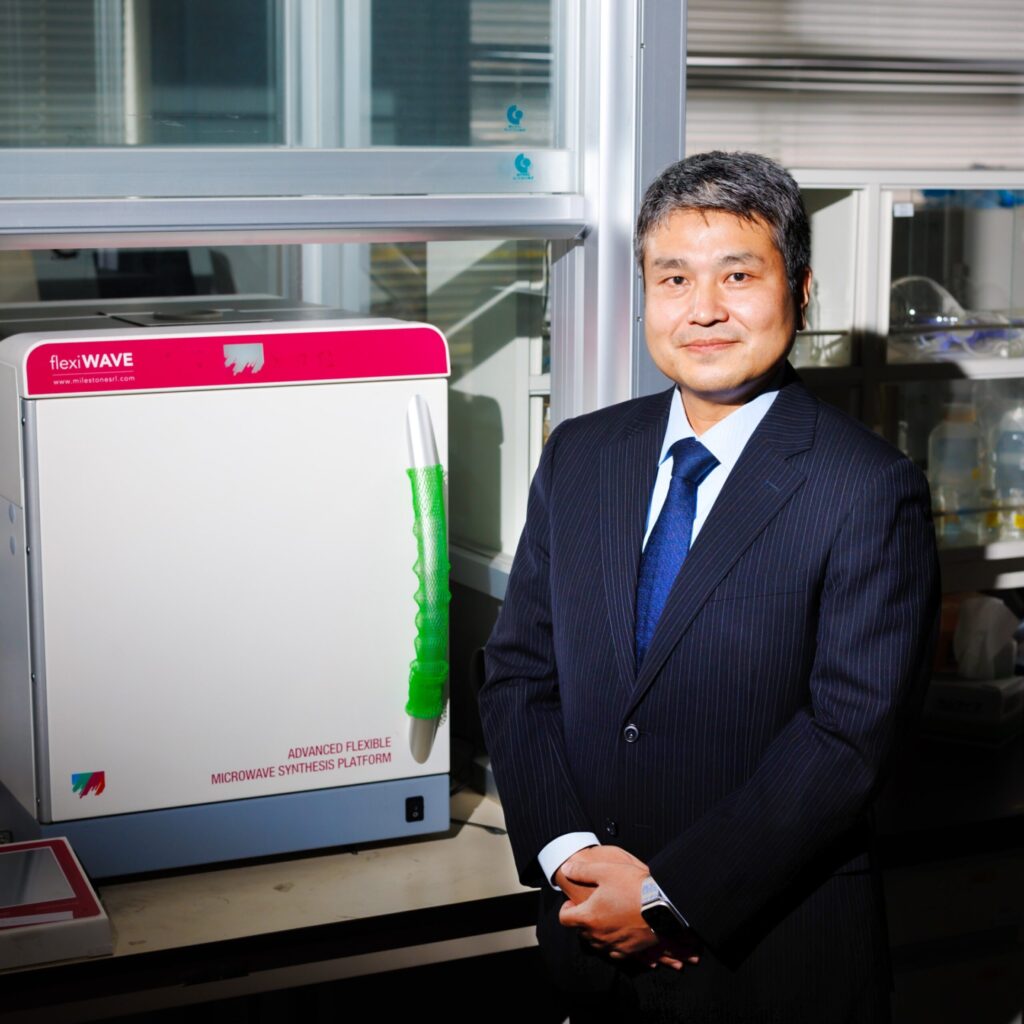

Professor Satoshi Horikoshi of the Faculty of Science and Technology studies the potential of microwave energy, and research ways to broaden its range of applications. Believing that microwaves have the ability to the power to innovate science, Horikoshi is driven by a desire to contribute both to the advance of learning and the growth of society.

Microwaves, as I’m sure you all know, heat foods with incredible speed. This is remarkable, don’t you think?

As a university student, I worked on developing new methods for purifying wastewater using light and chemical reactions. During my research, quite by accident I discovered that we could purify wastewater significantly more quickly by exposing it to both light and microwaves at the same time.

Initially, I thought this was because applying microwaves raised the temperature of the wastewater, but as I continued my research, I realized it had nothing to do with temperature. This remarkable phenomenon showed me that microwaves had applications other than just heating, and inspired me to begin researching them in earnest.

Today, I use microwaves in wide-ranging fields—the environment, chemistry, biology, energy, and food sciences—and research ways of improving both the global environment and our own lives.

Using student curiosity to guide microwave research topics

The general focus of my research lab is using microwaves as energy; however, I choose more specific research topics based on the interests and concerns of my students. In other words, my research combines microwave energy and student interests. In fact, the free-thinking of my students has led to many innovations.

One such innovation is the chemical recycling of plastics. Plastics are indispensable to our lives, but in recent years light has been cast on the various problems they bring about: they are a cause of marine pollution; they are not sustainable; and they contribute to global warming.

Thinking that, perhaps, microwaves could help, I began researching how microwaves might resolve plastic-related issues. My approach was simple. I mixed activated carbon—which is commonly used in air purifiers—with plastic waste, and heated it for a few seconds in a microwave oven; and I succeeded in transforming the plastic back into monomers—which are the raw ingredient of plastic.

Simply by exposing them to microwaves, we can transform plastics back into their basic building blocks over and over again—so eliminating the need to use petroleum, cutting down on waste, and resulting in zero pollution and zero CO2. Using this method, we can continue to use plastic in our lives.

Leveraging each other’s strengths with industry-academia collaborations

I am rather unusual in how frequently I engage in joint research with the private sector. An extremely large number of companies are interested in microwaves, and I have been involved in more than 30 joint research projects every year.

Recently, joint research into frozen foods has become more widespread. The coronavirus pandemic has resulted in increasing numbers of people staying in and eating at home—and consequently demand for frozen foods has risen manifold. Around the world, sales of frozen foods have also been rising as a strategy to prevent food loss, since frozen foods have lengthy “best-before” dates.

But it is not easy to defrost frozen foods. We use microwaves to defrost and heat frozen foods, but we can rarely defrost and heat them satisfactorily in one go.

We have created a new field of “microwave science,” and we are applying our learnings to research into defrosting and heating frozen foods. Working together with the private sector, our goal is to develop methods for “delicious defrosting and heating”—something which has long been considered impossible.

Applying microwave science to frozen foods will benefit everyone. By combining the respective strengths of academia and industry, we intend to make the impossible possible.

The book I recommend

“What on Earth Happened?: The Complete Story of the Planet, Life and People from the Big Bang to the Present Day”

by Christopher Lloyd, Japanese translation by Kyoko Nonaka, Bungeishunju

The author paints a linear history of the universe from its inception, enabling readers to acquire a holistic appreciation of its past. By discussing human civilization from multiple vantage points—including European, Asian, American, and ethnic minorities—he provides a bird’s-eye view of the history of humankind. A rewarding book, it offers a scientific explanation of the history of the universe.

-

Satoshi Horikoshi

- Professor

Department of Materials and Life Sciences

Faculty of Science and Technology

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of Chemistry, School of Science and Engineering, Meisei University, and received his Ph.D. in Science from the university’s Graduate School of Science and Engineering. Took on various positions—such as associate professor at the Tokyo University of Science —before assuming his current position in 2020. In addition to his role at Sophia, Horikoshi is President of the Japan Society of Electromagnetic Wave Energy Applications, part-time lecturer at Tokyo Gakugei University, a member of the R024 Committee at the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, a member of the research committee at the Japan Science and Technology Agency, and an editor of four international journals.

- Department of Materials and Life Science

Interviewed: November 2022