Professor Angela Yiu in the Faculty of Liberal Arts teaches and researches Japanese literature from the Meiji period to the modern day. She says that literature’s appeal lies in the fact that a work’s interpretations can vary infinitely depending on the reader. Currently, she is engaged in a Heisei “Literature in Japanese” project.

My initial encounter with Japanese literature was Yasunari Kawabata’s Snow Country when I was a high school student in Hong Kong. The weather on that day was sweltering hot, and I was waiting in a long line. I began to read Snow Country to pass the time and I was fascinated by the descriptions of Japan and the subtle communication between people in the book. Hidden within these seemingly insignificant day-to-day moments are often the seeds that can determine our future life course.

In university, I studied comparative literature and wrote my undergraduate thesis on Five Modern Noh Plays by Yukio Mishima. In graduate school, I studied under Edwin McClellan who famously translated Soseki Natsume’s Kokoro into English.

When hearing the word “literature,” one might get the impression that it’s a rigid and stuffy academic discipline, but that’s not at all the case. We can only experience so much in a single short lifetime. But through reading literature, we can come into contact with places and time periods beyond our immediate perception. We can imagine other lives with different experiences and bring the world right to our doorstep. We can think about what we would do if we were in a certain character’s position, and adding our own interpretation of the text is an exciting and creative endeavor.

A book’s possible interpretations are endless and there is no single correct answer

One of the representative works in Japanese modern literature is Kokoro by Soseki Natsume, and the book’s appeal is in how multi-layered it is. Reading it multiple times, we can appreciate it from a literary, aesthetic, historical, and psychological perspective, and in a sense, the plot develops like a detective novel, inviting us to pursue our curiosity and building up suspense.

Even reading it again after many years, we can discover new things such as life philosophy, human psychology, as well as ask profound questions about history and tradition.

Teaching literature in the Faculty of Liberal Arts is a true pleasure. In my classes, students come from more than 10 countries—sometimes as many as 20—with different backgrounds and experiences. It is a rare opportunity indeed to have such a diverse group of readers in the same place to discuss how the works of Yukio Mishima, Kenzaburo Oe, or Fumiko Enchi make an impact in our lives and thinking.

Our classroom provides an environment that transcends national and linguistic boundaries in our discussion of humanity, art, literature, as well as political and gender issues. The ways to read and interpret literature are infinite, and there is no such thing as a single “correct” reading.

I believe the most important thing is that students actively grapple with the stories, discover their own identities, and gain a sense of joy and accomplishment by reading.

Diverse and thought-provoking Heisei literature in Japanese

My current research is a long-term project that started in the final year of Heisei, and the theme is Heisei literature from 1989 to 2019. Each of the domestic and overseas scholars working on the project is responsible for writing one chapter based on a particular theme in the 30 years of Japanese modern literature in the Heisei period. It will be published as a book by the title of Multiple Voices in Heisei Literature by Sophia University Press in 2023.

One characteristic of Heisei literature is the inclusion of non-Japanese authors writing in Japanese and a lot of plurilingual literature that includes Japanese and other languages, such as English, Chinese, Korean, and German.

Authors featured in the book include Haruki Murakami, Minae Mizumura, Miri Yu, and others. There will also be a chapter on manga featuring My Brother’s Husband, or Otōto no Otto in Japanese. In recent years, manga has been one of the reasons why international students choose to study abroad in Japan, and My Brother’s Husband compels us to think about the theme of same-sex marriage in a diverse society that reflects the concerns of the current generation.

Another chapter will be on the intersection between literature and the environment and will showcase Paradise in the Sea of Sorrow by Michiko Ishimure who wrote about Minamata disease. The book project is shaping up to be a diverse and thought-provoking collection that goes beyond the traditional framework of literary scholarship and offers a completely new angle. I am aiming for a global readership of general and academic readers for this book.

The book I recommend

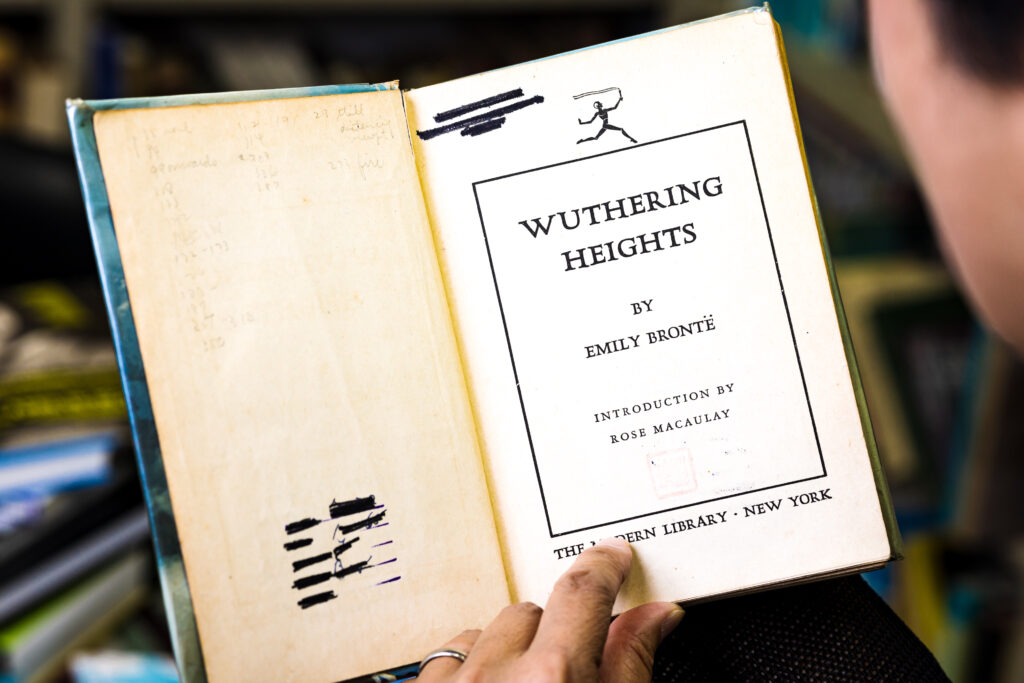

“Wuthering Heights”

by Emily Brontë, The Modern Library

When I read it for the first time at the age of 13, I didn’t quite understand everything, but Cathy’s passionate way of living left an impression on me. Ever since then, whenever I come to a big crossroads in life or even when I have to make a simple decision, I always ask myself: “Am I passionate enough about it?”

-

Angela Yiu

- Professor

Department of Liberal Arts

Faculty of Liberal Arts

- Professor

-

After receiving her BA in Comparative Literature and Asian Studies from Cornell University, Angela Yiu moved on to earn an MA in Asian Studies and a PhD in East Asian Languages and Literatures at Yale. She teaches and researches Modern Japanese Literature at Sophia University, where she has been since 1999.

- Department of Liberal Arts

Interviewed: June 2022