What are the systems necessary to balance conservation with the use of Natural World Heritage sites? Through efforts such as combating rats in the Ogasawara Islands, Professor Akemi Ori from the Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies undertakes research into methods for risk communication involving the participation of local residents and cooperation with local communities.

For about the past 10 years, I have been involved in natural conservation measures of the Ogasawara Islands as a member of the Ogasawara Islands Natural World Heritage Scientific Council under the Ministry of the Environment.

The animals and plants on the Ogasawara Islands—recognized as a Natural World Heritage site in 2011—evolve in their own unique ways to adapt to the environment of these isolated islands. A typical example are snails, but they are facing the threat of extinction due to predation by rats brought in by humans.

To eliminate rats on uninhabited islands, the Ministry of the Environment started aerial application of rodenticide in fiscal 2009. However, the residents were given incorrect information regarding the rodenticide and, due to growing distrust, the project was terminated in fiscal 2014.

Risk communication refers to stakeholders exchanging opinions and sharing information about risks. In particular, it is important to provide information and share opinions with local residents, but this was not carried out sufficiently. I came to work on this issue as an expert on risk communication.

Thinking about the balance between risks and benefits as a community

Risk communication evolved from conflicts with local communities caused by chemical substances. As ecosystems are formed on a delicate balance of mutual relationships between various species, the perspective of adaptive management—which responds flexibly to changes—becomes necessary in the conservation of ecosystems. Opinion exchange with the local community was carried out in a variety of ways, including workshops, while incorporating such a perspective.

I paid particular attention to finding out what issues local residents were facing and what information they wanted to know. In order for the workshop to be truly substantive, it was important to make everyone who participated feel that their opinions were properly heard and they obtained the information they wanted, so that workshops did not end as a mere formality. Therefore, I made thorough preparations, such as interviewing people, to understand their individual concerns and interests.

The residents’ doubts included “Why use aerial application?” and “Are you sure you have fully studied the methods for reducing risks from the spraying of rodenticide?” As a result of thoroughly answering these questions, we were able to deepen the residents’ understanding about the reasons for using rodenticide, and this led to the recommencement of this project.

In the conservation of Natural World Heritage sites, the local residents living there play the most important role. The value of the World Heritage site to the local community, the necessity of conservation, and the corresponding risks and benefits—a full understanding of these aspects and ensuring trust in policies are necessary.

Making Natural World Heritage sites the pride and treasure of local residents

I pay attention to a balance between fieldwork and the development of theories in my research. In September 2023, I brought some graduate students to visit Uken Village on Amami-Oshima Island.

Every year, the village holds a traditional festival called Hachigatsu Odori (August Dance) during the eighth month of the lunar calendar. Residents, students, and companies came together to think about how to use this festival as a tourism resource. The next issue is to develop theories about how the knowledge gained from such fieldwork can be applied to the communities of other Natural World Heritage sites.

The scope of my fieldwork has expanded from Ogasawara to Amami and Shiretoko. What should be done to make Natural World Heritage sites into treasures that local residents—especially children—want to protect? A major theme going forward is cooperation with people from the local communities while also incorporating the perspective of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and this is also my lifework.

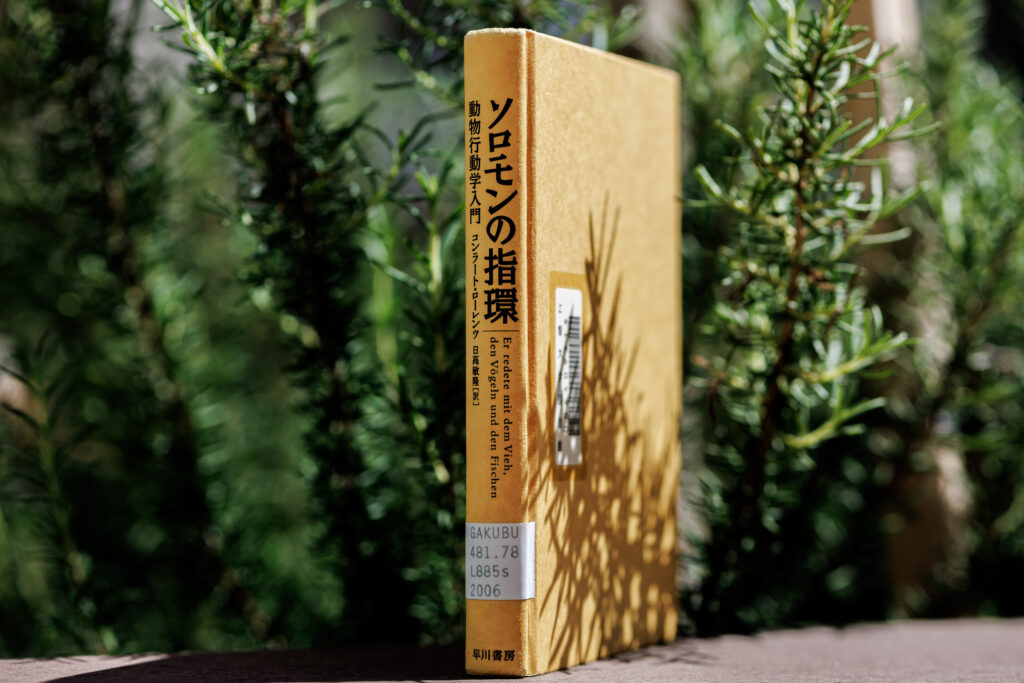

The book I recommend

“Er redete mit dem Vieh, den Vögeln und den Fischen”(King Solomon’s Ring: New Light on Animal Ways)

by Konrad Lorenz, Japanese translation by Toshitaka Hidaka, Hayakawa Publishing Corporation

I learned the basic stance of a researcher from this book. We tend to interpret animal behavior using human values, and this book made me realize that adopting perspectives that are close and in line with animals can lead to new discoveries.

-

Akemi Ori

- Professor

Master’s (Doctoral) Program in Global Environmental Studies

Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies

- Professor

-

Joined Tokio Marine & Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. after graduating from the School of Law, Waseda University. After leaving the company, completed the doctoral program of Hitotsubashi University’s Graduate School of Law. Took on the appointment of professor at the College of Law, Kanto Gakuin University before assuming her current position in 2015. Invited professor at Shanghai University since 2006, outside director of Mitsui Chemicals, Inc. from 2006 to 2010, and auditor-secretary of the National Institute of Technology and Evaluation since 2010.

- Master’s (Doctoral) Program in Global Environmental Studies

Interviewed: September 2023