Faculty of Foreign Studies Associate Professor Lucila Etsuko Gibo researches the language of immigrants to Brazil and their descendants. Here, she speaks about the characteristics of her main focus, the language of immigrants from Okinawa Prefecture, as well as the significance of that research and the importance of language.

From before WWII to 1978, approximately 240,000 Japanese citizens migrated to Brazil and became immigrants. Currently, if you also count the descendants of immigrants, the number of Japanese-Brazilians living in Brazil is approximately two million. My research is on the language spoken by these immigrants and their descendants. And within this topic, my main focus is surveying the language used by Brazilian immigrants from Okinawa Prefecture.

Immigrants who crossed the ocean without any opportunity to learn Portuguese started gradually using the local language through interactions with Brazilians there while still using Japanese. When two or more languages impact each other in this way, it is called “language contact.” This version of Japanese with Portuguese infusions that came to be used by Japanese people, and which was developed through language contact, came to be called the Colonia-go.

A unique language blending Japanese, Okinawan, and Portuguese

People from Okinawa were the most present among the Japanese immigrants coming into Brazil. As they spoke the Okinawan language, which is one of the Ryukyu languages, Japanese, Okinawan, and Portuguese blended together to create a unique language that was itself different from the Colonia-go. I have dubbed this language the “Brazilian-Okinawa Colonia-go,” and am surveying what kind of characteristics it has.

I became interested in this research because of my own heritage as a child of an immigrant in Brazil from Okinawa Prefecture. I was born a second generation Brazilian, and I grew up hearing the Okinawan and Japanese my parents spoke at home. When I first started formally learning Japanese at a Brazilian university, I became aware that the Japanese I had thought natural up to then was actually very different.

For example, I would sometimes be corrected by the teacher when I said things that Okinawan people often say such as, “kasa wo kaburu (wear an umbrella)” instead of “kasa wo sasu (use an umbrella),” “shatsu wo tsukeru (attach a shirt)” instead of “shatsu wo kiru (wear a shirt),” and “kuruma kara iku (go from car) instead of “kuruma de iku (go by car).” Through these sorts of experiences, I began to become interested in language.

Another reason for my research is, immigrants who speak Okinawan are gradually decreasing, so I felt I must record their speech for posterity. Words are cultural assets in and of themselves, so hearing immigrants speak connects to knowing about their history. I decided that I wanted Japanese youth who do not know about the immigrant experience to learn why immigrants made up their minds to move from Japan to Brazil, how they learned to speak and fit in the unfamiliar environment of a new country, and what kind of struggles they faced. This is also a large motivation in continuing my research.

My research method starts by meeting directly with immigrants in Brazil and recording casual conversation with an IC recorder. I convert the recorded voice to text, and then use that to set about discovering how words are being used and what the grammatical characteristics are.

In a globalized society, language change is an inevitable phenomenon

Language contact is a daily phenomenon in countries with many immigrants and areas where countries are connected to each other. Things like “having differences in pronunciation or grammar” should not be thought of as a negative. Language by its very nature is a thing that changes amidst interaction among people from different countries due to globalization. In Japan as well, laborers from foreign countries are said to be on the rise, and I believe this will most likely mean the Japanese language will change little by little.

On the other hand, local dialects in Japan are being lost, and I want these to be cherished as cultural elements. Currently in Okinawa Prefecture, there is a language revival movement to record old words and dialects in an attempt to pass them along to the young generation. It is my hope that my research could also benefit this movement in some way.

The book I recommend

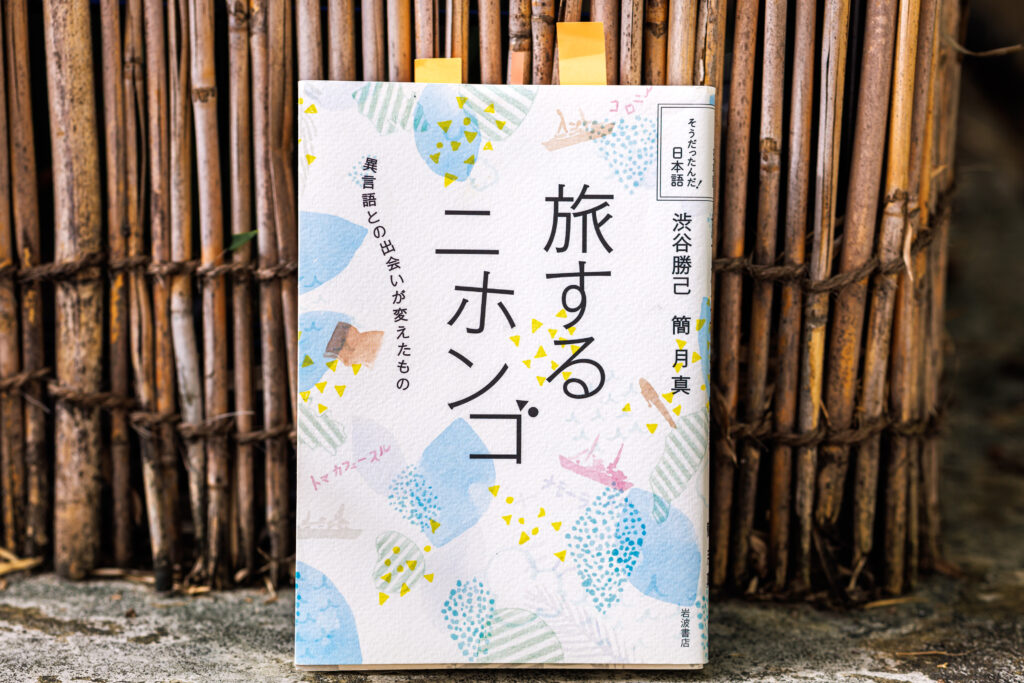

“Tabi Suru Nihongo” (The Traveling Japanese Language)

by Katsumi Shibuya and Yuehchen Chien, Iwanami Shoten

The subtitle for this book is “What encounters with other languages has changed,” and it presents an easy-to-understand explanation of the changes in the Japanese language through interactions with people from different countries, from Japanese language passed on by Japanese immigrants abroad to Japanese language that came to be used by people living in countries Japan colonized before WWII.

-

Lucila Etsuko Gibo

- Associate Professor

Department of Luso-Brazilian Studies

Faculty of Foreign Studies

- Associate Professor

-

After graduating from the Faculty of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (with majors in Portuguese Language and Japanese Language) at the University of São Paulo, received her M.A. in Languages and Cultures (Ryukyuan Language Studies) at the University of the Ryukyus Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences and her Ph.D. in Linguistics from the same program (Ryukyuan Language Studies). Served in her current post since 2014.

- Department of Luso-Brazilian Studies

Interviewed: November 2022