Respect for fundamental human rights is one of the three pillars of the Constitution of Japan. But Associate Professor Fumihiko Azuma of the Faculty of Law questions whether “human rights” has become nothing more than a catchphrase, and discusses what Japan can learn from laws in Europe, where awareness of human rights is more prevalent.

My fields of research are European and Italian laws. I focus particularly on human rights, and investigate the relationship between EU law, Italian law, and the European Convention on Human Rights.

EU law refers to the laws of the European Union, and applies to all 27 EU member states. Italian law refers to the laws of Italy, and applies to Italy alone. The European Convention on Human Rights is designed to protect human rights, and applies to all 46 member states of the Council of Europe. Italy is a member of the EU, and of the Council of Europe. As a member of the EU, it is required to observe both EU law and its own national laws.

EU law, Italian law, and the European Convention on Human Rights represent distinct systems of laws; as such, they at times offer different verdicts. In my research, I examine judicial decisions to investigate why their verdicts may differ.

Creating better protections for human rights

To give you an example of these differences, let me discuss a judicial decision regarding freedom of religion.

An old edict provides that a crucifix should hang in every classroom of every Italian public school. One day, it was claimed that this edict violates the right to freedom of religion for non-Christians. According to the Constitution of the Italian Republic, it was ruled that the right to freedom of religion was not infringed upon.

However, an initial trial at the European Court of Human Rights found that the edict infringed upon the right to freedom of religion as outlined by the European Convention on Human Rights. Italy appealed, and a higher court subsequently ruled that it did not, in fact, violate the right to freedom of religion.

As you can see, some cases can be found one way according to Italy’s domestic laws, and another according to Europe’s international laws. When these systems of laws contradict each other, it invariably sparks debate as to which is correct; and this, in turn, encourages the establishment of even better protections for human rights.

In the 20th century, Europe was gripped by totalitarianism and was unable to prevent the human rights of minority groups from being violated. European nations implemented reforms in the wake of these bitter experiences, and they continue to explore ways to strengthen human rights today.

Japanese indifference to the constitution

As I learned more about European protections for human rights, so I came to recognize the importance of constitutions. A constitution is akin to a shield carried by individual citizens against the actions of the state, which are set in motion by the majority. Even if the state unsheathes its sword, the constitution ensures that the state cannot swing unjustly at its citizens.

If a government tries to disregard the constitution, that government forgoes its right to rule and must be forced out of office. But in Japan, few people appreciate the significance of the constitution.

It may be a blessing that most Japanese can go about their daily lives without having to think about either the constitution or human rights. Members of the majority are rarely subject to discrimination, and are unlikely to have to appeal to human rights.

But things are different in the EU, where people come and go across national borders. People who, in their own countries, were citizens and part of the majority, are foreigners and part of the minority in other EU member states.

It can also happen that rights that are recognized in France may not be recognized, say, in Italy, and vice-versa. For these reasons, EU citizens are constantly thinking about and questioning the nature of human rights.

In Japan, too, globalization is progressing. It is becoming increasingly hard to ignore the presence of foreign residents and other minorities. Many Japanese feel that minority issues do not concern them, but anyone of us can become a minority overnight, simply by becoming ill or getting injured.

It is too late to start thinking about human rights after we have become a minority, been discriminated against, and suffered violations of our human rights. It is my duty, I believe, to draw on my understanding of Europe and communicate the importance of creating a legal system in which the quiet voices of the minorities are not unfairly drowned out by the booming voices of the majority.

The book I recommend

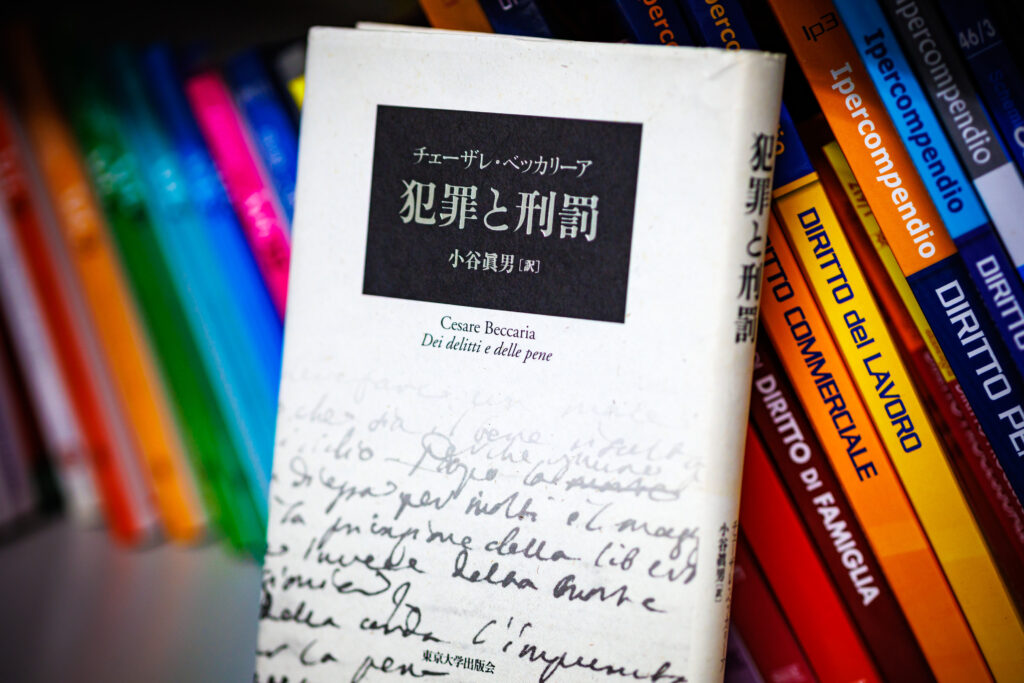

“Hanzai to Keibatsu”(On Crimes and Punishments)

by Cesare Beccaria, Japanese translation by Masao Kotani, University of Tokyo Press

Written by the Italian jurist Cesare Beccaria, this book argues for the abolition of both the death penalty and of torture. It was written in the 18th century, but the clarity of its logic and reason is astonishing. Counter to European and international trends, Japan retains the death penalty—it is for us an extremely pertinent read.

-

Fumihiko Azuma

- Associate Professor

Department of International Legal Studies

Faculty of Law

- Associate Professor

-

Associate Professor Fumihiko Azuma graduated from the Department of Italian Language, Faculty of Foreign Languages, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, and received his Ph.D. in law from the Graduate School of Law, Keio University. After working at the Japanese consulate in Milan, and as an associate professor at the School of Global Humanities and Social Sciences, Nagasaki University, he was appointed to his current position in April 2021.

- Department of International Legal Studies

Interviewed: October 2022