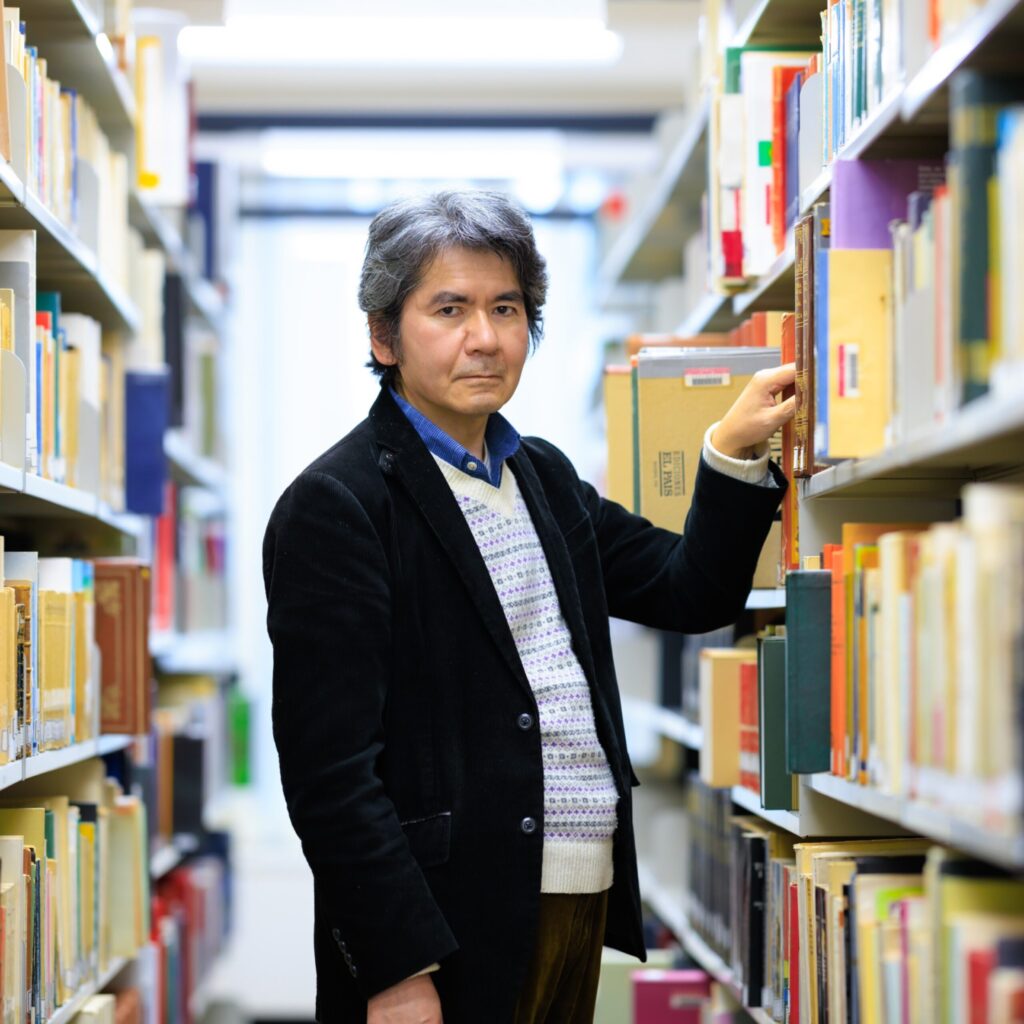

Professor Atsushi Ichinose of the Faculty of Foreign Studies specializes in the linguistic analysis of Creoles, a group of languages that develops when different peoples meet. He studies the structure of the Creoles used in African nations where Portuguese is also spoken. But what is the appeal of languages that arises out of contact between different cultures?

When people who speak different languages come into contact, new languages can be created. I find this wonderful, and so I have dedicated myself to the study of Creoles.

When people who speak different languages interact, if the circumstances are right, it can happen that a language known as “Pidgin” is formed; this is a type of language with a limited vocabulary and a simple grammatical structure.

If, again, the circumstances are right, it can then happen that Pidgin becomes the mother tongue of a group of people; when Pidgin becomes a people’s first language, it is called “Creole.”

There is an unspoken agreement between researchers to only use the term “Creole” to refer to languages that developed during or after the Age of Discovery.

Understanding Creole requires wide-ranging knowledge

I am particularly interested in the Creole spoken in Guinea-Bissau, a country situated on the west coast of Africa. Guinea-Bissau came under Portuguese rule in the 16th century, and only gained independence in the 1970s. Its official language is Portuguese, but the majority of its people speak Creole on a daily basis.

Although the development of Guinea-Bissau Creole was influenced by Portuguese, simply knowing Portuguese is not sufficient to fully understand the Creole it spawned.

Let me give you an example. In Guinea-Bissau Creole, there exists the short word “i.” The sentence “Jon i pursor” means “Jon is a teacher.” Since this word “i” links “Jon” and “pursor,” it was long thought to stem from the Portuguese word “é”—which is similar to the English word “is.”

But after careful study of the word “i,” I wrote an article suggesting that it was derived not from “é” but from “ele”—the third person singular-form of the nominative pronoun. My article succeeded in almost completely overturning established theory in the Portuguese-based Creole studies.

One of the clues to my discovery was the Chinese phrase “shiki soku ze ku,” which means “everything is nothing.”

My hypothesis was that the “i” in Guinea-Bissau Creole was grammatically equivalent to “ze” in the phrase above—and means “is equivalent to.” In this case, wide-ranging linguistic knowledge helped free me from preconceived notions.

Guinea-Bissau Creole also makes temporal distinctions that are not made in Portuguese. For example, “ora ku” means “when someone does” and “oca” means “when someone did.” Although this distinction is not made in Portuguese, I ascertained that it is made in native West African languages such as that spoken by the Mandinkas.

As it happens, “oca” is also used in Mandinka to mean “see.” But the Creole “oca” is derived from the Portuguese verb “achar” meaning “to find.” As you can see, the study of Creole requires knowledge not only of the superstrate—the language inherited from the European colonizers—but also of the substrate—the native language of the colonized.

Drawing on the knowledge of native Africans

In learning African languages, which form the substrate of the Creole I study, I am extremely grateful to have made the acquaintance of a learned historian named Mario Sissoko. He is Bissau-Guinean, and is fluent in about 10 African languages.

On-site linguistic investigations are indispensable to the study of Creole languages but, for me, simply listening to what Sissoko has to say is an equally important channel of research.

I have recently developed an interest in how the linguistic status of various African countries is changing. Previously, Creole was regarded as inferior to European languages—a negative opinion shared even by some Africans.

Over the last few years, however, Africans themselves have started to affirm the “normality” of Creoles, and advocated its use as an official language. This development is of great interest to me, and I am fascinated to see how African culture and society evolves going forward.

The book I recommend

“Pijin kureoru shogo no sekai – kotoba to kotoba ga deau toki”(The world of pidgin and creole – when languages collide)

by Masayuki Nishie, Hakusuisha

I first became interested in Creoles after attending a lecture by the author, Masayuki Nishie. This book seeks to answer the basic question: what is the nature of human language? It distils the author’s ideas, cultivated over decades of on-site investigations and research, into simple, concise language. I recommend it highly as a primer to Creole languages.

-

Atsushi Ichinose

- Professor

Department of Luso-Brazilian Studies

Faculty of Foreign Studies

- Professor

-

Professor Atsushi Ichinose received his B.A. and M.A. from the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. After working as a special researcher for the Embassy of Japan in Portugal, and as a lecturer then assistant professor at the Faculty of Foreign Studies, Sophia University, Ichinose was appointed to his current position in 2007. He has served as Director of both the Center for Luso-Brazilian Studies and the European Institute, Sophia University, and as the Chairman of the Japan Luso-Brazilian Association.

- Department of Luso-Brazilian Studies

Interviewed: December 2022