Associate Professor Tomoki Kunieda of the Faculty of Humanities researches the history of governmental and corporate public relations. According to Kunieda, “the history of public relations is the history of communication.” Here, he talks about the joy and significance to be found in researching what is, in Japan, a relatively new field of study.

Public relations (PR) can be defined as communication—and approaches to communication—carried out by governments and companies to achieve their objectives. All types of organizations engage in PR on a daily basis, to achieve a wide range of goals: companies, for example, might carry out PR to encourage customers to buy their products; governments may use PR to encourage citizens to carry out infection prevention measures. The methods used vary greatly, from getting coverage on news programs to tweeting on social media sites. In my research, I trace the history of such activities.

Companies equivalent to present-day PR firms first appeared in the U.S. at the start of the 20th century. However, PR itself has existed since ancient times. In Ancient Rome, stones inscribed with the proceedings of the senate were regularly put on display for citizens; in medieval Germany, the emperor gave land to poets who wrote poems and songs extolling his virtues.

The reasons behind the prominent PR strategy of the British Royal Family

When investigating the history of PR, it becomes clear that the intensification of PR activities in a certain industry or organization is occasioned by some sort of trigger. Let us take the British Royal Family as an example. Today, the British Royal Family is well known for its active media exposure and use of social media; this stance can be traced back to 1997, when the British people criticized the Royal Family for its silence following the death of Princess Diana in a car accident. In Japan, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe adopted a policy of “diplomacy of panoramic views,” visiting 80 countries and regions around the world during his tenure while receiving various local media coverage; the impetus for strengthening global PR came from intensifying international competition.

In my research, I primarily deal with two types of documents: first, the PR materials of the organizations under study; and second, third-party literature related to these PR materials or their content. It frequently happens that organizations only include convenient information or explanations in their PR materials. It is therefore essential to consider other viewpoints to uncover the truth of the matter. By comparing these two types of materials, the essence of PR—which lies somewhere between the truth of the matter and the organization’s official stance—gradually becomes clear. Through such research, government PR could reveal the realities of democracy while corporate PR could reveal unexpected realities behind environmental issues. I personally find this fascinating.

The challenge of an unexplored field

Actually, I did not start out intending to study the history of public relations. As a graduate student, I was looking into why certain social movements attracted media attention. Before long, I was learning about things not discussed in books and research papers on media and journalism theory in Japan—about the methods governments and companies use to attract media attention, or about the PR industry that helps organizations increase their media exposure. Despite being an important practice or an industry that influences society, it was hardly researched in Japan and its history was largely unknown even overseas. And so I thought: let me take up the challenge of researching an unexplored field.

The history of PR is not a field that has immediate practical use. However, when you investigate when, why, and how governments, companies, and citizens’ groups communicated from ancient times to today, we can understand current issues and predict the future from a historical perspective. Going forward, I hope to further my research and to discuss with students and the wider society the past and the present of PR, its possibilities and its problems. It is often said that Japan is bad at PR. For the sake of the future of both Japan and the world, I would like to contribute to the development of PR specialists.

The book I recommend

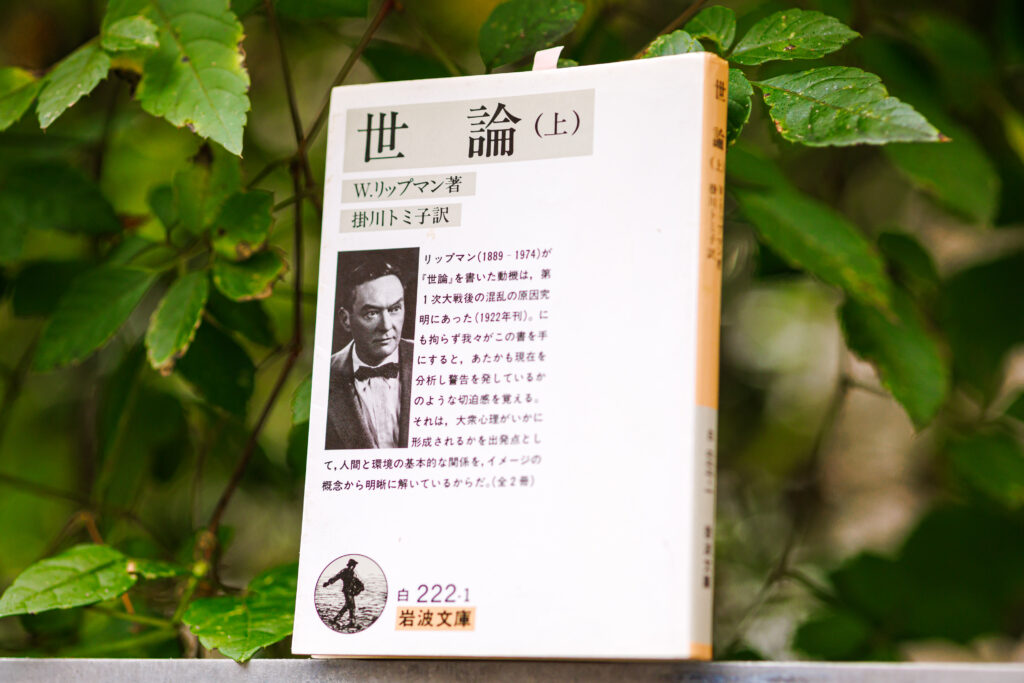

“Yoron”(Public Opinion)

by Walter Lippmann, translated by Tomiko Kakegawa, Iwanami Shoten

Published 100 years ago in 1922, Public Opinion is a classic in journalism, in which Lippmann analyzes the influence that mass media has on society. I read this book when I was in my fourth year at university—it encouraged me to think deeply about the relationship between media and society, and about how the media should be.

-

Tomoki Kunieda

- Associate Professor

Department of Journalism

Faculty of Humanities

- Associate Professor

-

Associate Professor Tomoki Kunieda graduated from the Department of International Legal Studies, Faculty of Law, Sophia University; he received his Ph.D. in Journalism at the Sophia University Graduate School of Humanities. After working as an assistant professor at the Department of Communication and Culture, Faculty of Communication and Culture, Taisho University, and as an assistant professor at the Department of Journalism, Faculty of Humanities, Sophia University, Kunieda was appointed to his current post in 2019.

- Department of Journalism

Interviewed: September 2022