Japan’s birthrate continues to decline. One factor driving this trend is the heavy burden placed on mothers. To address these circumstances, Associate Professor Atsuko Saito of the Faculty of Human Sciences is exploring how society can collectively rear children.

The expression “parent lottery” implies that a child’s life rests solely on the shoulders of their parents. However, when we consider the various facets of child-rearing, there are many aspects that cannot be handled by parents alone.

Although “it takes a village to raise a child,” this ideal is far from the reality in Japan. This is why my research focus on how to enhance society’s involvement in parenting.

Is the mother really the sole nurturer in a baby’s life?

In Japan there is an entrenched notion that the parenting of a young child is the responsibility of the mother. This is frequently discussed in relation to “attachment theory” in developmental psychology, whereby an infant first forms a close attachment with the mother before forming bonds with others. However, recent research has shown us that this attachment can be formed with others, including the father.

In fact, the idea that the father goes off to work while the mother looks after the home is a contemporary concept. In the Edo period, farmers and townspeople worked regardless of their gender, and wet nurses raised the children of samurai and nobles. The belief that the mother is the best for the child is a relatively recent notion.

I have also looked at this from a biological perspective. In addition to developmental psychology, I also specialize in evolutionary psychology, a field which observes humans as animals. Comparing humans and other primates through this lens reveals our unique attributes.

Human infants are born in a relatively immature states compared to those of other primates, taking more time and effort to raise. It is also more physically taxing to give birth as a human, which means the mother must start caring for her baby in an exhausted state.

Furthermore, the breastfeeding period is short at around two to three years — sometimes even less than one year — with short intervals between subsequent births. It is a tremendous burden to raise a young child while caring for an infant; outside assistance is essential.

Parenting as a community

For other primates, males play almost no part in the rearing of infants. This is true even for gorillas and chimpanzees, which are considered close relatives of humans; only the mother cares for the young. With that said, there are some primates that behave similarly to humans, with those other than the mother assisting in child-rearing immediately after birth.

The common marmoset, a small monkey, will give birth to two sets of twins in a year. This means the mother will be breastfeeding while pregnant with her next set of twins. At birth, the combined weight of twins is 20% of an adult and will reach 100% by the end of their breastfeeding period. Child-rearing takes a lot of work, so the father and the older siblings actively take part, sharing food and carrying the babies on their backs. This is an example of a species in which others will step in to support when the mother needs parental support.

As such, it is natural that human mothers also receive support from others when raising children. However, no such system exists in the modern Japanese society, which is why I want to create one.

We interview a wide range of people, including parents currently raising children; children; childcare workers; parents who have raised children; and those who have no experience raising children; in search of a method to realize the ideal of “a village raising a child.” A system in which many people, including non-family members, dynamically take part in child-rearing will ease the burden placed on parents and benefit the children and everyone involved. This, I believe, is the path to improving Japan’s birthrate.

The book I recommend

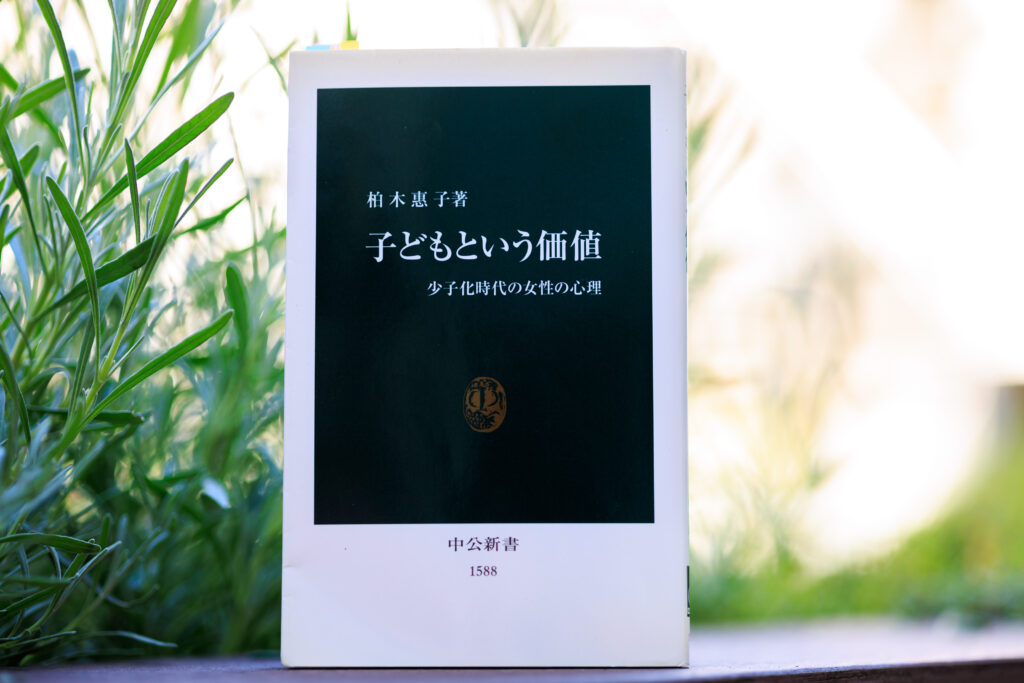

“Kodomo to Iu Kachi”(The Value of Children)

by Keiko Kashiwagi, Chuo Koron Shinsha

Drawing from a wide array of data, this book taught me that the entrenched notion that a mother should naturally find happiness in raising a child is not necessarily true. It helped me realize that it is okay to work while raising children and that it is okay to depend on others.

-

Atsuko Saito

- Associate Professor

Department of Psychology

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Associate Professor

-

Atsuko Saito graduated from The University of Tokyo’s Department of Life and Cognitive Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, and earned her PhD at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. She served as an Assistant Professor and lecturer at The University of Tokyo and subsequently as a lecturer at Musashino University’s Faculty of Education before assuming her current position in 2018.

- Department of Psychology

Interviewed: July 2023