When people learn new things, professor Koyama of the Faculty of Liberal Arts says that a “transfer of learning” occurs. He believes that researching this transfer process will result in more effective ways of learning and refine assessment methods in education.

Initially, I was interested in the process of people acquiring foreign languages, and I used tests that measured the effectiveness of learning to infer someone’s abilities. After that, through research and actual experience, my interests expanded beyond just languages to encapsulate learning as a whole.

My research explores instances when we leverage prior knowledge and experiences to deal with an unknown and difficult problem, especially how this may relate to more durable learning and solving complex problems. Applying what we’ve already learned when thinking about a novel and complex problem or how to understand new information is called the transfer of learning. As a matter of fact, I consider transfer of learning and critical thinking—a topic receiving much attention in recent years—to be one and the same.

However, there is still no universally accepted definition of critical thinking. I’ve researched and compared different critical thinking tests and there are essentially two different ideas; the first being that it is based on the specific demands of each academic discipline, and the second being that it is a general skill that can be used across a wide range of fields. My own definition leans more towards the latter, without rejecting the value of domain-specific knowledge in problem solving and thinking.

Surprised at the strong effects brought about through group learning

In my research comparing the effects of individual learning with group-based, collaborative learning, I was surprised at the stark difference between them. The research took place in a class that required students to interpret complicated graphs, and the collaborative learning class clearly understood the content more deeply, and exhibited a higher retention rate of not only the surface-level information, but also the deeper structures of understanding that novices tend to not notice. Furthermore, in a control group, the teacher first gave explicit instructions about the surface and deep structures, yet the learning effect for the collaborative learning group was statistically significant and higher than the control class and in the class in which students were working alone.

The reason for this is because the transfer of learning is occurring between the group members, which is called group to individual transfer. I believe that actively pointing out things you notice or verbalizing a moment of understanding to others leads to deeper comprehension and retention of concepts.

Fostering people who can solve environmental issues

My newest research interest is about decarbonization and environmental issues. To solve these difficult problems before us, critical thinking or transfer of learning is crucial.

In a paper I’m now working on with other researchers, we are writing about how to equip people with eco-literacies. For environmental issues, knowledge alone will not solve them; without action, the knowledge is meaningless. Therefore, in examining the reasons why people do not take action for the environment, we are formulating a hypothesis that a person’s disposition to take action may matter more than the amount of knowledge one has.

On the other hand, when bringing these issues up in class, the knowledge of students is quite one-sided. Their primary source of information is the news, which is either full of pessimism, or is overly optimistic about the prospects of green energy such as wind and solar. I ask students to consider that wind and solar can supply less than 1% of our energy usage, so it can’t really be a solution unless it can produce 99 times more than it currently does. I also ask them to think about the existence of other types of alternative energy sources that are being developed both in Japan and elsewhere, such as molten-salt Thorium reactors.

By facing problems head on, mustering the facts at their disposal, and knowing the world as a larger picture all help broaden students’ horizons. Critical thinking or transfer of learning is vital in their daily lives and for making good choices.

The book I recommend

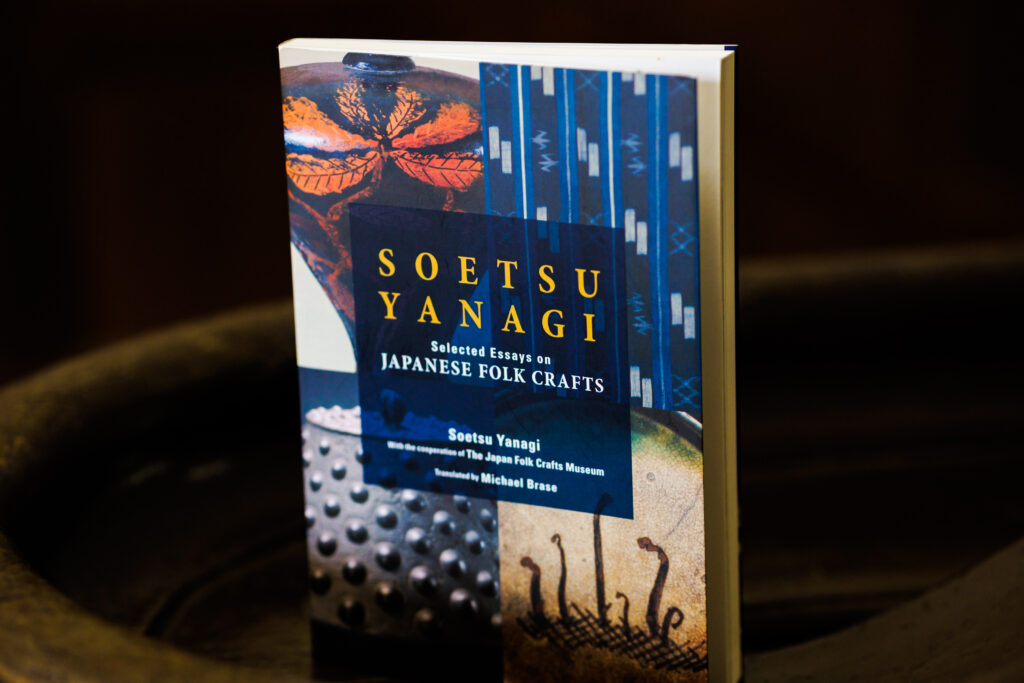

“Selected Essays on Japanese Folk Crafts”

by Soetsu Yanagi, translated by Michael Brase. Published by the Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

Why do we feel no mental satisfaction when using something that has been mass produced? The answer, “because it was made by someone who despises their job,” this passage resonated with me. Education is the same way, I think. I sense that the unique methods used to cultivate craftspeople who have a passion for their craft overlaps with the pedagogy of teaching and the principles of collaborative learning and learning transfer.

-

Dennis Koyama

- Associate Professor

Department of Liberal Arts

Faculty of Liberal Arts

- Associate Professor

-

Dennis Koyama received an MA from the University of Hawaii, Manoa and a PhD from Purdue University. He is an educational researcher and statistician and has taught and lectured in a variety of contexts in North America, Asia, and the Middle East. Dennis has published research on several subjects, including critical thinking, collaborative learning, transfer, L2 writing, language testing, and professional development. He has been at Sophia since spring 2019.

- Department of Liberal Arts

Interviewed: August 2022