In Latin America, rural-urban migration has brought about accelerated urbanization. At the same time, aggressive economic development projects in the countryside have caused environmental destruction which generate different kinds of social conflict. Professor Noriko Hataya from the Faculty of Foreign Studies has been carrying on her fieldwork and transmitting findings in search of local-based solution.

I have been engaged in Latin American Studies with a special focus on the Republic of Colombia, South America. Before moving to Sophia University, I worked as a researcher at the Institute of Developing Economies of Japan External Trade Organization (IDE-JETRO).

At that time, there was no precedent for conducting research about Colombia, and I embarked on research feeling my way around. Since then, I have been visiting Colombia almost on a yearly basis, except during the period when overseas travel was not possible due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

When I was an undergraduate student, I had an opportunity to study abroad in Mexico, through the Japan-Mexico Government Exchange Program. In the early 1980s, most of the countries in Latin America experienced the period of rapid urbanization brought about by rural-urban labor migration. Low-income settlements, so-called slums, were created in the outskirts of major cities.

Coming across such a situation in Mexico City, I came to be interested in learning more about the social issues in Latin America and later this motivation led me to undertake local-based research.

Approach to Colombia from the perspective of local people, suffering from armed conflict

How the issues of poverty and disparity should be tackled in search of solution? How far the current thought on development could work for it?

In a study conducted in Colombia in the 1990s, it was found that the establishment of basic infrastructure such as water supply by the government could not keep up with rapid urbanization, resulting in residents buying land from illegal developers and building their own settlements in the outskirts of cities.

In these areas, workers who came to cities from the countryside subsequently brought in their families to establish their homes there, causing the population in the outskirts to increase. In other words, cities expanded even though they had poor infrastructure.

Furthermore, Colombia is a country plagued by armed conflict for decades. Many internally displaced persons (IDPs) from rural areas due to the armed conflict arrive at cities. They could rely on temporary humanitarian aid but alternative job generation for them has been short. As a consequence, they have come to live in low-income settlements.

In the course of learning about the processes of these urban migrants’ fight for their life, upgrading of housing and related infrastructure, I felt the necessity of conveying their voices to policymakers.

Fortunately, I was given the opportunity for a joint research project with Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular (CINEP), a Jesuit research organization that works on social issues in Colombia.

The Jesuit priest who served as the director of CINEP at that time later established a consortium of nongovernment organizations in one of the remote rural areas facing severe armed conflict, with the aim to fight together with local people, against the risk of being displaced.

Based on community participation and placing importance on their initiatives, the consortium sought ways to improve living conditions, economic independence and autonomy of local people.

The priest gave me a piece of advice. “To learn about the real situation of poverty and impact from conflict, it is necessary to visit the local communities and listen to the people living there.” There were many things to learn from the activities of local communities, which helped them to maintain their livelihoods without abandoning their own land or neighborhoods.

A university’s raison d’être lies in its commitment to society

Through my encounter with this priest, I came to ponder on the purpose of universities and the mission of academics. I arrived at the conclusion that, besides studying the dilemmas and injustice of society, universities and academics must also commit to them. Otherwise, there is no raison d’être.

In countries gifted with natural resources, such as Colombia, a development model that relies on market mechanisms could serve to generate various dilemmas and conflicts. Going forward, I hope to continue giving back the results of research to people of the local communities. To do so, it is necessary to communicate—including using our own voices—in ways that influence public opinion and the minds of policymakers.

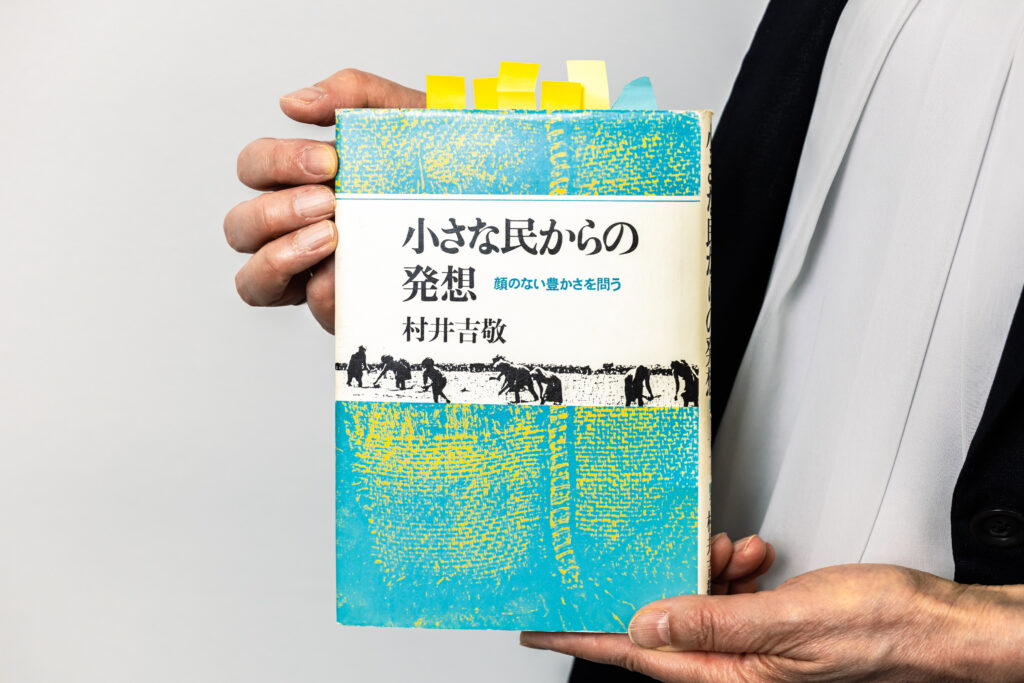

The book I recommend

“Chiisana Tami Kara no Hassō: Kao no Nai Yutakasa wo Tou” (Ideas from the Little People—Questioning Wealth Without Faces)

by Yoshinori Murai, Jiji Press

A book by the late emeritus Professor Murai, specialized in Southeast Asia’s economy, discussing development from the perspective of local-based area studies. His critical view revealed that, in the development of Indonesia, the Japanese government’s aid did not help to improve the local people’s lives. This book has been the milestone for my fieldwork and critical thinking toward mainstream discourse on development.

-

Noriko Hataya

- Professor

Department of Hispanic Studies

Faculty of Foreign Studies

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of Hispanic Studies, Faculty of Foreign Studies, Sophia University, and received an M.A. from the University of Tsukuba Graduate School’s Division of Area Studies and another M.A. in Regional Development at the Interdisciplinary Centre of Development Studies (CIDER), Universidad de los Andes. Received her Ph.D. in Geography at University College London. Starting her academic carrier as researcher at the IDE (subsequently merged with JETRO), she moved to Sophia University as assistant professor at the Department of Hispanic Studies, Faculty of Foreign Studies, Sophia University in 2001 and in 2008, assumed current position.

- Department of Hispanic Studies

Interviewed: June 2022