In a world where traditional pregnancy and birthing customs remain strong, Laotian midwives continue to explore ever better care for expectant and nursing mothers, with one foot in traditional practices and one foot in modern medicine. From her experience surveying local midwives firsthand, Department of Nursing Associate Professor Rie Sayama speaks on the role she wants Japanese midwives to play.

In the old days, birthing was accomplished with the help of people in the community. And in the midst of this approach, an array of rituals and customs praying for easy deliveries and post-birth recovery arose. My research is on how midwives support expecting and nursing mothers, with a focus on the Southeast Asian countries where traditional customs still remain, and the juxtaposition of modern medicine therein.

Laos has been a particular center of focus for me. That story started with something that happened when I was working at a local hospital upon joining the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers as a midwife in my twenties. We received a notification that a woman in charge of prenatal checkups was feeling unwell after giving birth at her own house, and wound up dying as a result. Shocked, I visited the house, but she had already been cremated. It was there that I began thinking deeply about Yu Fai and Kalam Kin, the age-old customs surrounding birth.

Research prompted by the death of a female in charge of prenatal checkups.

Yu Fai is the custom of putting the bed near or atop a charcoal flame and lying near the flame for several days to a month after giving birth. It is believed to speed the recovery of the womb, and going outside is absolutely prohibited during this period. Kalam Kin is a custom of restricting the diet for a set period.

The woman I mentioned was having a poor post-birth recovery, but she was unable to go for a checkup at the hospital during the Yu Fai period. The day she died was the day she was attempting to go to the hospital after Yu Fai had finally finished. When I heard this, I was paralyzed on the spot out of shock.

After this incident, I decided that I wanted to thoroughly research how Laotian midwives treat and care for expectant and nursing mothers. I returned to Japan, entered graduate school, and returned to Laos as a researcher. With cooperation from hospitals, I conducted interviews with midwives and expectant and nursing mothers. I used the Lao language and worked hard to blend into the local society. In this way, I went back and forth between Japan and Laos and compiled my research paper.

What became clear in my research was that, while struggling with the tension between traditional customs and modern medicine, Laotian midwives make all sorts of adjustments in an attempt to protect expectant and nursing mothers. They recognize customs, but propose methods that do not result in harm to health. For example, they may say things like, “If you are too hot from Yu Fai, reduce the heat of the fire,” or, “Kalam Kin can hamper breast milk production, so you should increase the items that you are allowed to eat.”

Simply opposing customs obstinately will not solve the problems. With this in mind, the midwives gave thoughtful care customized to each individual patient. I will never be able to forget the death of that woman after birthing, but learning about the earnest efforts of Laotian midwives has provided some measure of emotional respite.

Helping Japanese midwives take a more active role

In Japan, birthing at hospitals and other medical facilities is the main custom, and midwifery is progressing based mainly on evidence from modern medicine. Because of this, it could be said that midwives do not often intercede deeply into the cultural background of the lifestyles and birthing of expectant and nursing mothers. However, in the past giving birth at one’s home was the main custom, and midwives provided fine-tuned care for everything from discussions about the body to emotional concerns. They understood regional customs and traditional rituals, and provided holistic care.

I think it would be ideal if, in the modern day as well, midwives could provide more support in terms of the lifestyle and culture of expectant and nursing mothers. And I want to continue communicating ideas and thoughts emerging from my research in the educational environment. I believe that doing so is a way for my research to benefit society.

Additionally, while research does exist on the customs of expectant and nursing mothers from a folklore angle, studies compiled by midwives from the medical professional perspective are few in number. From this viewpoint as well, I feel compelled to continue my research, all the while contributing records of traditional and cultural aspects regarding pregnancy and birth.

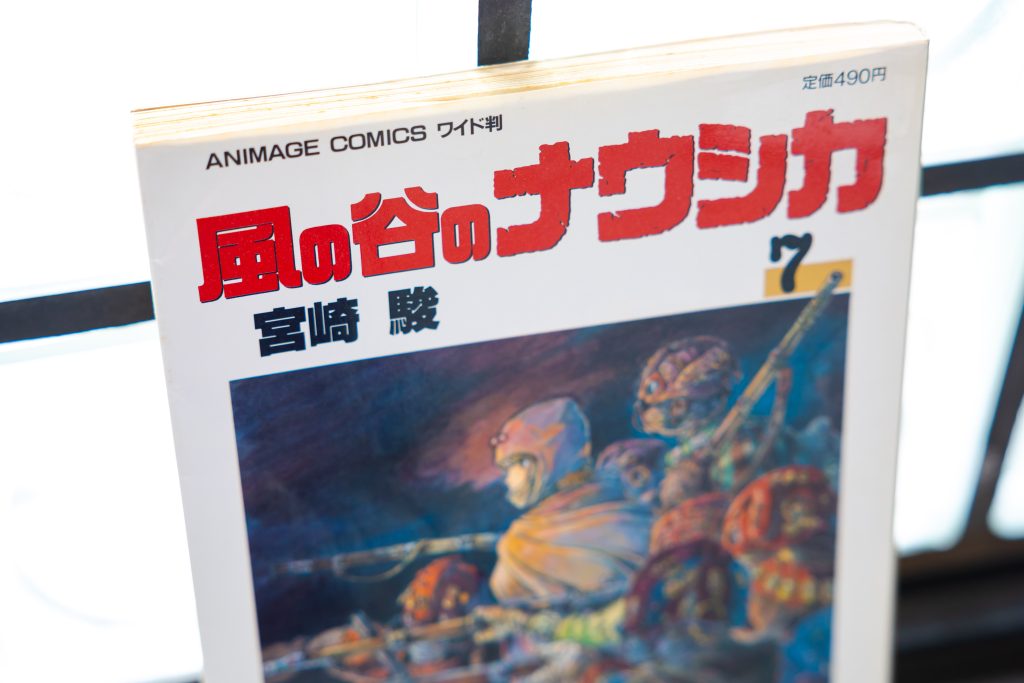

The book I recommend

“Kaze no tani no naushika” (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Vol. 7)

by Hayao Miyazaki, Tokuma Shoten

Set in a post-apocalyptic world beset with a strange ecosystem, this story tells the tale of a girl searching for the proper paths for people and nature to take. The final volume came out when I was in high school. I always carry in my heart the desire to live my life like Nausicaä.

-

Rie Sayama

- Associate Professor

Department of Nursing

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Associate Professor

-

Associate Professor Sayama received her Ph.D in Nursing from Toho University Graduate School of Nursing. She was assigned to Laos as a Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteer (midwife). After serving in the Faculty of Nursing at Toho University, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the Faculty of Health Care at Teikyo Heisei University, she attained her current position in April 2021. She is also active as a Director of the Japan Institute of Midwifery Evaluation and Vice Chairperson on the Professional Committee on Midwifery of the Japanese Nursing Association.

- Department of Nursing

Interviewed: July 2022