Professor Takeshi Kawasaki of the Faculty of Foreign Studies specializes in German politics. When Russia invaded the Ukraine, the recently-elected German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was faced with a dilemma—one colored by the historical relationship between Germany and Russia.

In February 2022, the Russian army invaded Ukraine. NATO member states were unanimous in their condemnation of Russia and immediately imposed economic sanctions. But Germany, the de facto leader of the EU, was so passive in its approach that it was criticized by the U.S. for being “out of step” with its allies. Why was this?

Many countries around the world are either outright in their support of Russia, or have officially declared neutrality but in practice are helping Russia by not participating in economic sanctions.

For Japanese, such a stance may appear inexplicable. But if we wish to understand why such a stance is rational for these countries—or, more accurately, for their incumbent governments—we must not only investigate the current state of their politics, economies, and diplomacy, but also their histories.

By taking a multifaceted and broad view of these countries’ relations with Russia, their economies, and their cultures, we can shed light on their trains of thought.

The tumultuous relationship between Germany and Russia in the 20th century

The history of German-Russian relations is a seesaw of discord and compromise: the two countries were unable to trust each other, but nor were they able to sever ties. Even today, many Germans would prefer to leave a path open for Russia to reconcile with Europe—despite its transgressions—rather than see Russia become a client state of China.

In this respect, Germany is at odds with the U.S., which has publicly stated its intention to critically weaken Russia—a country it views as an adversary.

During the Second World War, Nazi Germany unilaterally ripped up the non-aggression pact it had signed with the Soviet Union (present-day Russia), invaded its erstwhile fellow-signatory, and for a while occupied Ukraine and other Soviet territory.

But it was the Soviets who ultimately won the war: Germany was divided, and East Germany fell under the influence of the U.S.S.R. Germany reunified in 1990, and the Soviet Union was almost simultaneously dissolved—and Russia and Ukraine became independent nations.

Since then, Germany has adopted a liberal form of diplomacy toward Russia, in the belief that deepening economic cooperation would help discourage political confrontations and disputes.

Germany relies on Russia for much of its natural gas supply. Indeed, former-Chancellor Angela Merkel devoted great energy to building the Nord Stream, an undersea pipeline that enabled Germany to bypass politically unstable Ukraine when importing natural gas from Russia.

Yet Merkel also supported the Westernization of Ukraine, and actively worked to remedy the situation after Russia had annexed off Crimea. Germany has struggled to balance humanitarian needs with a desire not to antagonize Russia.

The role of area studies in building peace

The relationship of trust that Germany thought it had built with President Vladimir Putin collapsed following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Chancellor Scholz was faced with a dilemma: safeguard economic interests of the German public, or succumb to the international community’s demands for cooperation, particularly on humanitarian issues.

And this dilemma is key to understanding why Germany was so lukewarm in its condemnation of Russia, following the country’s invasion of Ukraine.

In retaliation for the sanctions imposed upon Russia, President Putin has suspended exports of natural gas, while the economic community has all but given up on Russia; for these reasons, Chancellor Scholz is gradually being compelled to side with the U.S.

Although public opinion has—perhaps inevitably—hardened against the Putin administration, German society remains divided. The Scholz administration is trying to identify the most appropriate response.

Bilateral relations do not reverse overnight; rather, they are intimately linked to the histories, cultures, economies, and the national traits of the two countries in question. To build peace, we must seek to strengthen mutual understanding by learning from each other’s experiences and sharing knowledge. And I believe that area studies has a vital role to play.

The book I recommend

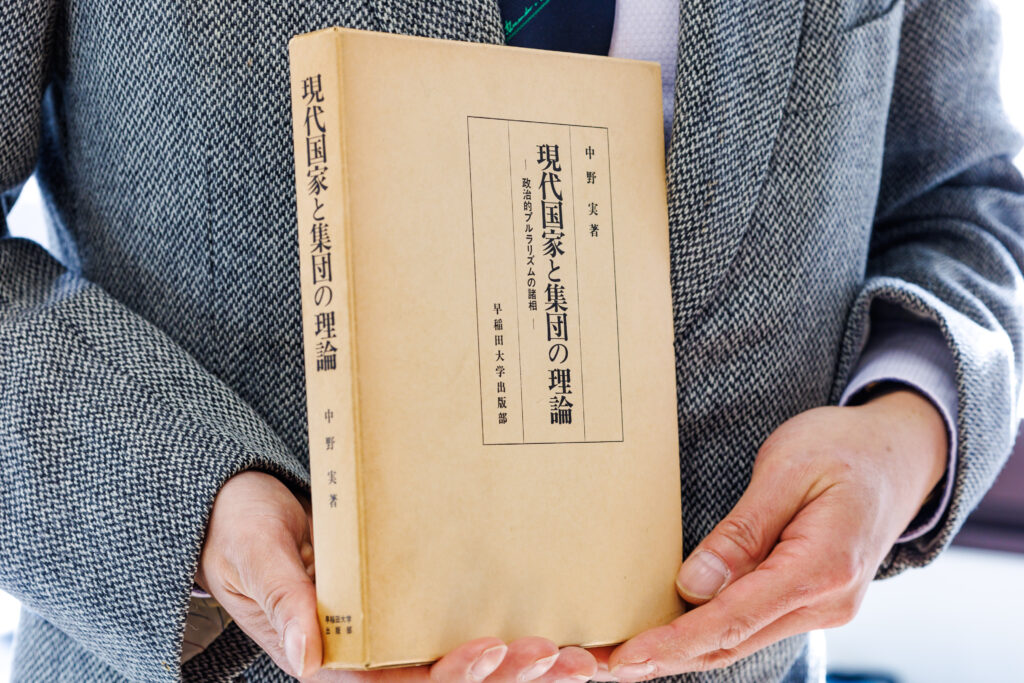

“Gendai kokka to shudan no riron“(Modern states and group theory)

by Minoru Nakano, Waseda University Press

Group theory has long been a central theme of American political science, and this book discusses it from many angles. It was often brought up at my post-grad study meetings. Initially, I found it hard to comprehend, but when I finally did, I was filled with admiration for the author. I hope you encounter such a book, too.

-

Takeshi Kawasaki

- Professor

Department of German Studies

Faculty of Foreign Studies

- Professor

-

Professor Takeshi Kawasaki graduated from the Department of German Studies, Faculty of Foreign Studies, Sophia University, and received his Ph.D. in political science from the Graduate School of Political Science, Waseda University. Kawasaki began working at Sophia University in 1996, and was appointed to his current position in 2012.

- Department of German Studies

Interviewed: January 2023