Associate Professor Naoko Morita of the Faculty of Humanities is a historian of western history. She is also an expert in the history of emotions, which looks at historical evidence through the prism of emotion. Here, Morita talks about her passion for this approach to history, and its potential for interdisciplinary research.

Historiography relies on historical documents to analyze past events, and provide a clearer understanding of the events and the times they reflect. I specialize in the history of emotions, a relatively new field that analyzes and researches history from a perspective of emotions.

The history of emotions is a new branch of history, which in Japan has only started to gain traction in the last ten years. Many people consider the historical studies to be an impersonal enumeration of facts concerning who did what and when.

But some form of emotion invariably lurks behind these facts—the history of emotions seeks to shine a light on these emotions, and offer new interpretations that differ to conventional historiography.

Emotions have been traditionally treated as a nuisance in historiography. This is because historiography, which objectively analyzes mainly written historical documents, cannot include subjective feelings that are not written in the documents.

But according to a historian of emotions, this all changed on September 11, 2001. The terrorist attack in the US led to an outpouring of disbelief, anger, and sadness that could not be expressed in words—and historians therefore had to focus their attention on these very emotions more than ever.

In fact, there have long been many events or trends that cannot be explained without recourse to emotions, such as the witch-hunts and nationalism. Peer pressure and unconscious cooperation have also on occasion conspired to create history.

Historiography seeks to gain insight into the past through the vestiges that peoples have left behind. Looking at history from a perspective of emotions adds new color to these insights—and it is in this that the appeal of the history of emotions lies.

Duels and honorary citizenship in 19th-century Germany

My area of expertise is 19th-century German history, and I am particularly interested in the duels that contemporary male students participated in. These were not real duels—they did not seek to kill each other—but they did fight with real swords. Naturally, these duels resulted in much bleeding and widespread wounds.

Why, then, did these German students participate in such savagery on a daily basis? Was it a display of masculinity? Did they fear being ostracized by their peers? Did the prevailing social conditions make it inevitable? Because of honour? My goal is to interrogate the meaning of these duels by focusing on the emotions that underlie them.

I am also engaged in research into honorary citizenship. By the start of the 19th century, German states had established a system whereby citizens who had made significant contributions to their cities were bestowed with honorary citizenship. But who was chosen, and what were the criteria?

Public history records merely highlight the people honored—yet a closer look at the minutes of the city council reveals the existence of dissenting voices. Drawing attention to this discord imparts an emotional color to the acts carried out by the city and its peoples.

The potential for interdisciplinary research

In principle, researching the history of emotions entails close reading of as many historical documents as possible—this includes contemporary publications, minutes, and newspapers, but also ego documents such as love letters. On occasion, I compare these materials with literary works.

To consider human emotion more, I also apply learnings from the results of psychology and neurosciences, and literature and philosophy. This potential for interdisciplinary collaborations sets the history of emotions apart.

What are emotions? How do emotions function within history, and how do they shape society? Today, the intensity of our emotions is sharpened by social media; learning from past events that were induced by human emotions, and cultivating the ability to understand these events in relative terms can benefit people alive today.

Going forward, I intend to continue interacting with my colleagues in adjacent fields of study of emotions and with researchers abroad, and I hope to show people just how fascinating the history of emotions is.

The book I recommend

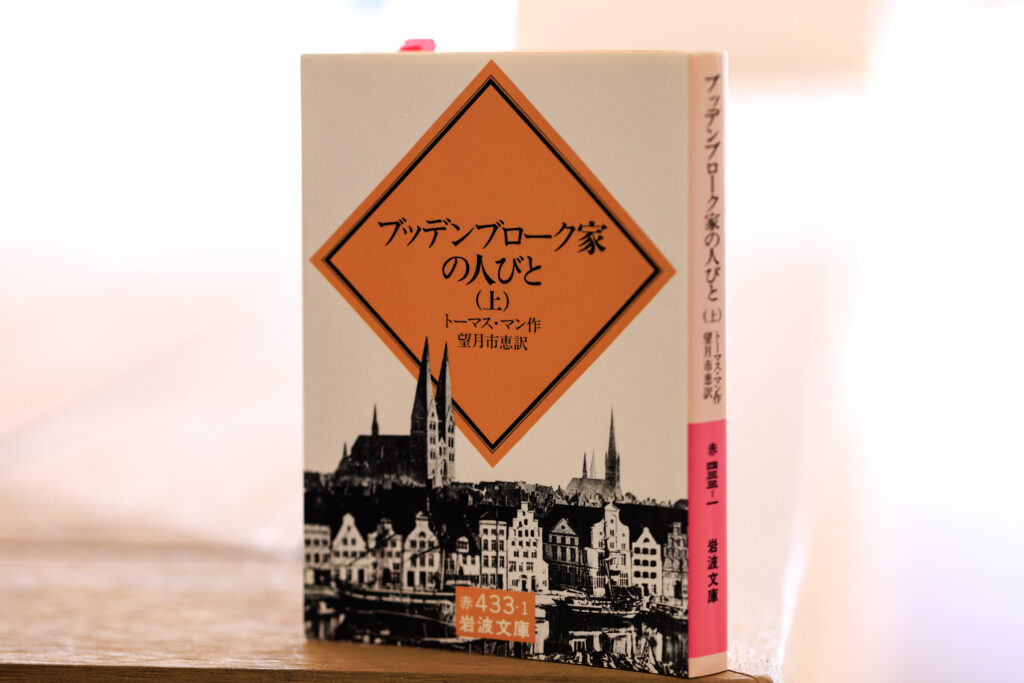

“Buddenbrooks”

by Thomas Mann, Japanese translation by Ichie Mochizuki, Iwanami Bunko

Set in 19th-century Germany, Buddenbrooks traces the decline of a prominent family over the course of four generations. The female protagonist of the story is very much in the shadows of patriarchy, but she is portrayed in an absolutely fascinating manner. Although Buddenbrooks is a work of fiction, it touches upon various historical events. I would recommend the novel to anyone with an interest in German history.

-

Naoko Morita

- Associate Professor

Department of History

Faculty of Humanities

- Associate Professor

-

Associate Professor Naoko Morita graduated from the Faculty of Letters, The University of Tokyo, and completed her Master’s degree in European and American Studies at the university’s Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology; she received her Ph.D. from the Faculty of History, Philosophy and Theology, Bielefeld University. After working as an associate professor at the Faculty of Letters, Rissho University, Morita was appointed to her current position in 2023.

- Department of History

Interviewed: May 2023