Faculty of Global Studies Professor Namie Tsujigami is a researcher of gender issues pertaining to women in the Middle East, conducting fieldwork centered on Saudi Arabia. She brings a unique approach to gender theory, a field that tends to be dominated by Western perspectives.

Gender does not refer to biological sex, but rather to sex-based roles formed by society and culture. Centered on Saudi Arabia, my surveys and research employ a multi-faceted approach to examine the power dynamic between men and women.

Saudi Arabia is considered by many to be a country where women are oppressed. Polygyny persists and patriarchal elements are strong. It was not until several years ago that women were granted permission to drive automobiles. As of 2022, The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap ranking places the country at 127 among 146 nations.

These circumstances raise the question: Are women in Saudi Arabia merely oppressed “victims?”

Examining the reality via women networks, removed from Western bias

Japan does not have a long history of research on gender in the Middle East. When I began my research some 20 years ago, there was only a handful of gender researchers focused on the Arab region. Inaccurate information can lead to misunderstandings; I myself had thought that Arab women were poor people with limited freedom. However, the women I met there weren’t the victims I had imagined.

The first thing that surprised me when I lived in Saudi Arabia twenty years ago as senior researcher at the Embassy of Japan was the robustness of the women’s network. Arabs value socializing, and so do women. Women routinely interact with family, relatives and friends to build and maintain networks. Their socializing generally begins when the sun has set and the weather is cooler. These gatherings can go late into the night, with women oftentimes not returning home until the following day. While this is not permitted for unmarried women, I felt these married women were afforded greater freedom than their Japanese counterparts.

When women go outside, they wear a veil and abaya – a long black outer garment – but at women’s gatherings, they enjoy their fashionable attire worn underneath. From a Western perspective, veils and abayas are seen as symbols of suppression; however, some local women view them positively. For example, they may say that “having an abaya lets me work outside of the house while honoring my faith,” or that “abaya allows me to easily fit in at any formal or public occasion, making it convenient.”

In recent years, the number of business women has increased, and women’s networks seem to have played a major role in this. As women earn more income and contribute to the household economy, there will be changes in power relations between men and women.

Realizing that a lack of understanding of other cultures exists within yourself

It is of course true that there is inequality between men and women in the Middle East, such as inequality pertaining to marriage, divorce and inheritance. But can we judge what is right or wrong solely through the lens of Western gender theory?

I emphasize the importance of listening to locals as much as possible in my research. The topics covered in my current research range from labor, consumption, entrepreneurship to driving and fashion. This research has been published as academic papers as well as in magazines and books. By shedding light on misunderstandings of gender in the Middle East, I hope to bring awareness to the sense of superiority that exists within us. Unilaterally viewing a group of people as “victims” leads to discrimination.

As for Japan, even though it is a developed nation, it is only 116 on the aforementioned Global Gender Gap ranking. The solutions to improve this situation will not necessarily come from Western gender theory alone. I believe my research will be one resource in this pursuit.

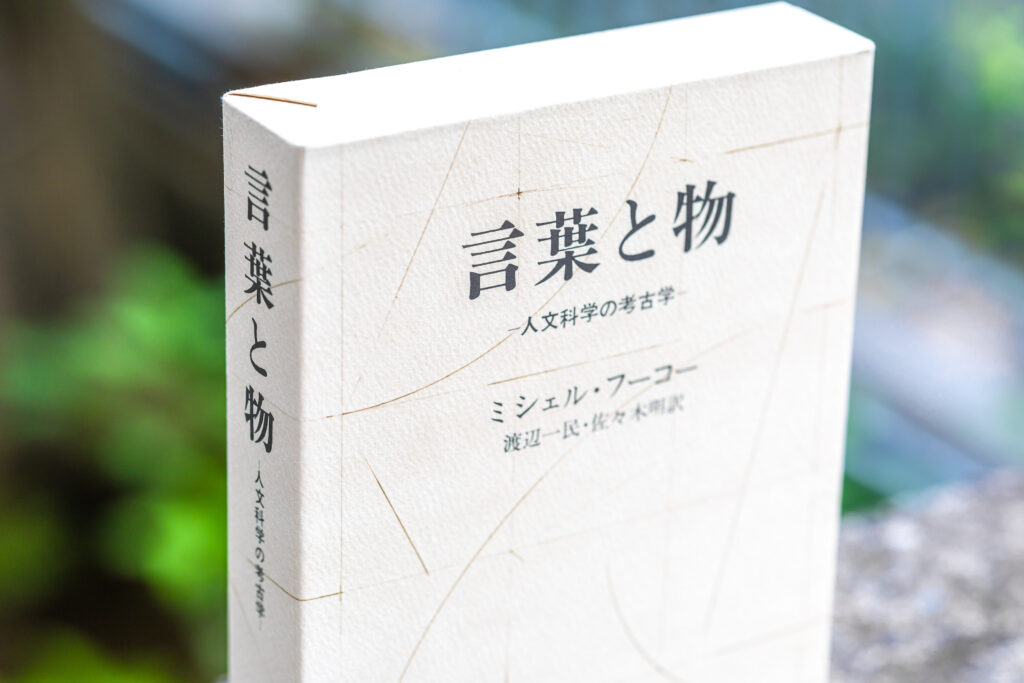

The book I recommend

“The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences”

by Michel Foucault; Japanese translation by Kazutami Watanabe and Akira Sasaki, Published by Shinchosha.

This book taught me the fact that many of our values originated in modern Western society and are not immutable truths. The same can be said of gender roles of men and women. This book taught me to be skeptical of the very foundations of anything created by humans.

-

Namie Tsujigami

- Professor

Department of Global Studies

Faculty of Global Studies

- Professor

-

After graduating from the Foreign Studies Faculty of the former Osaka University of Foreign Studies and completing a graduate program at the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies in the UK University of Exeter, Professor Tsujigami received her Ph.D in Philosophy from the Graduate School of International Cooperation Studies at Kobe University. She served as a full-time lecturer at the Faculty of Cultural Studies in the University of Kochi, a Specially Appointed Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in the University of Tokyo, and an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Global Studies in Sophia University before assuming current position.

- Department of Global Studies

Interviewed: June 2022