Specializing in modern Chinese history, Associate Professor Christian Hess of the Faculty of Liberal Arts studies the northeastern region of China from the 1920s to 1950s. His research focuses on the history of the port city of Dalian, which was influenced by Russian and Japanese colonialism. He explains that understanding modern Chinese history is important to better China-Japan relations.

My specialty in Chinese history is the northeastern region of China during the 1920s to 1950s. This region is known as “Manchuria” in Japan. The ’20s to ’50s in that region is a fascinating period in Chinese history, as many significant changes happened in a short span of time. Interestingly, not much research has been done yet in this area. Although Chinese history and China-Japan relations in earlier times have been studied extensively, a large gap exists in the literature on modern Chinese history in the first half of the 20th century. The reason for this is entirely political. Since the parties involved – Russia, Japan, and China – have different perspectives on the period, a lot of connections and narratives have unfortunately been lost. My mission is to fill this gap in Chinese history.

I am particularly interested in the port city of Dalian located in the northeast. It is a unique city influenced by both Russian and Japanese colonialism, and it is now a part of China. After World War II, the area known as “Manchuria” was returned to China. However, Dalian remained influenced by the Soviet Union, which used some of the area as a military base.

I first visited Dalian while I was a student. I was fascinated by a place which went through amazing geo-political changes – as a Russian colony, then as a Japanese port, back to the Soviet Union as a militarized zone, and then finally to communist China. My research focuses on the process of its transition – similarities between the periods as well as the changes that took place. Numerous evidence of Japanese occupations – both good and bad influences – can be detected in the city.

The Chinese government tries to paint a negative image of Japan, but the local sentiment there towards Japan is complex and doesn’t match the standard narratives pushed by the Chinese government. The local population shares very warm and friendly feelings toward Japan with, for example, the most popular foreign language to learn in Dalian being Japanese. Political feelings and personal feelings are very different in the area. Politics skews the real image of China-Japan relations.

New research: exploring stories of Chinese population in Japan

Some of my current research focuses on the Chinese population in Japan, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s. Since it was hard to enter China with its zero-Covid policy and to conduct research within the current political climate, I adjusted the focus of my near-term research to Chinese people in Japan. Although there has been a lot of research on Korean immigrants, less work has been done on the Chinese population here during the early to mid-20th century.

Chinese immigrants were fewer in number than Korean immigrants during this period. Their stories haven’t been explored – where they came from, where they went, what they were doing, and where they are now. I have discovered that among the graduates of Sophia University in the 1950s, there were some Chinese from Taiwan. There was also a Chinese political association formed during the American occupation after the war. There is a lot to discover about Chinese immigrants in Japan.

Filling the gap of political narratives and personal stories

Given the current political climate in China, doing research on the ground or working with our counterparts in China is very difficult. Because researchers in the field can’t access many materials, Chinese studies scholars outside of China face great challenges. This could be a threatening factor for the global order as the Chinese relationships with other countries including Japan could spin out of control. The future of the region depends upon good China-Japan relations.

As an educator residing in Tokyo, I believe my role is to teach a version of China-Japan relations which aren’t politically influenced. I want to fill the gaps between the political narratives and people-led stories. It is impossible to disconnect history and the current international landscape. Teaching modern Chinese history is critical for the future of the region.

The book I recommend

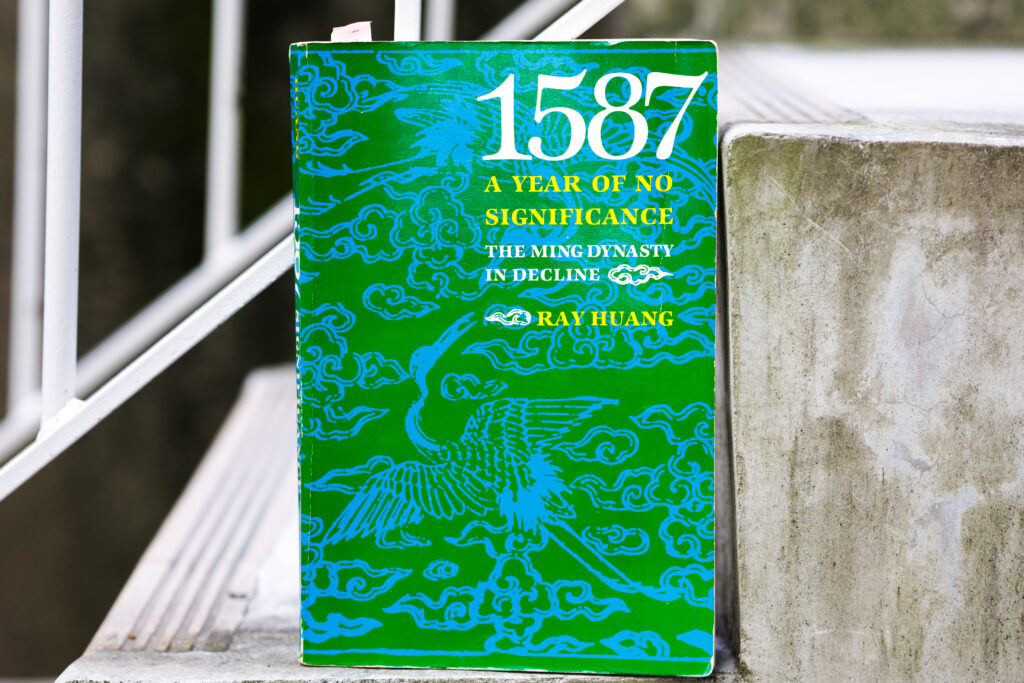

“1587, A Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline”

by Ray Huang, Yale University Press

This was a textbook from one of the first Chinese history classes I took. No significant event happened in 1587 in Chinese history. But the author provides a deeper look into the ordinary year and analyzes it to be “the beginning of the end.” It made me aware of a creative approach to the study of history.

-

Christian Hess

- Associate Professor

Department of Liberal Arts

Faculty of Liberal Arts

- Associate Professor

-

Christian Hess received a BA in History from the University of California, Davis and MA and PhD in Modern Chinese History from the University of California, San Diego. Afterward, he served as an assistant professor at the University of Warwick in the UK, and later joined Sophia University in 2012.

- Department of Liberal Arts

Interviewed: October 2022