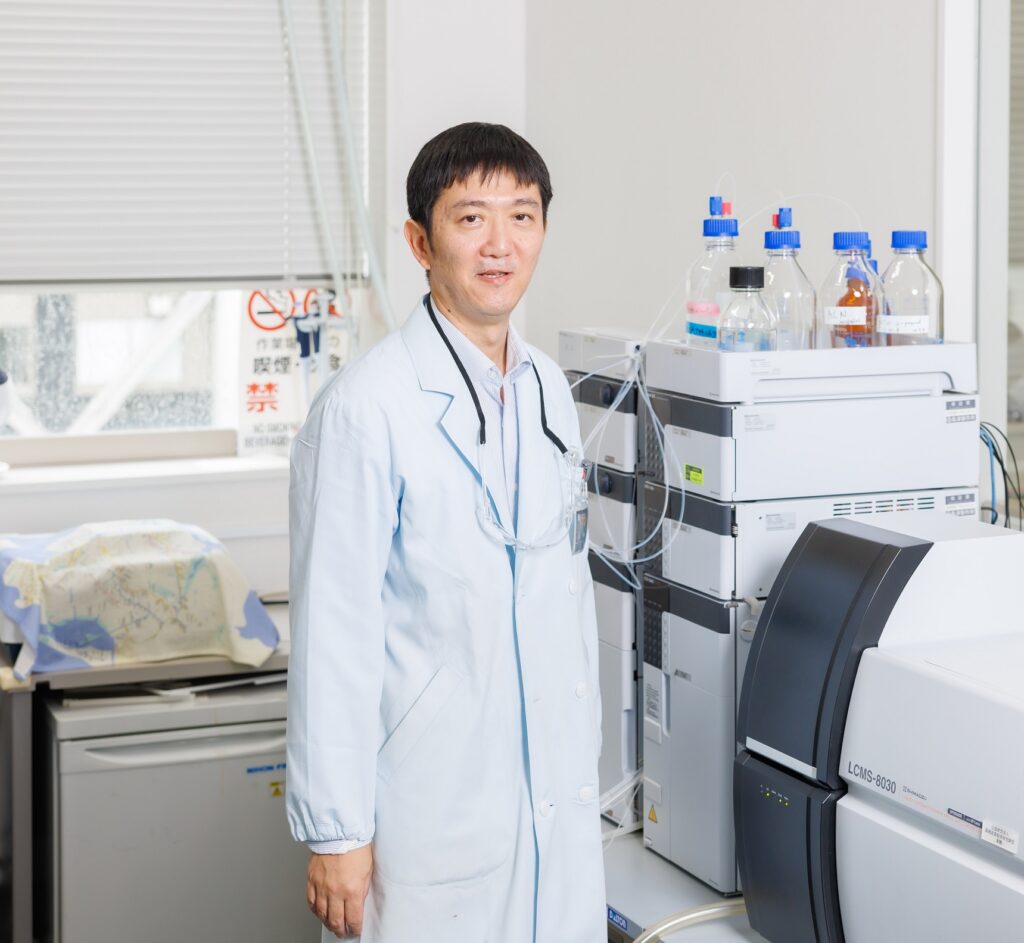

Professor Toyonobu Usuki of the Faculty of Science and Technology conducts research on amino acids synthesis and analysis for diagnosing chronic lung disease. Meanwhile, he has techniques for extracting active ingredients from plant waste. Here, he discusses the potential of naturally occurring substances, and the rewarding aspects of engaging in research that benefits society.

My research area covers natural products chemistry, a subfield of organic chemistry that encompasses all substances created by organisms, including humans, animals, plants, fish, and microorganisms.

One of the molecules I am particularly focused on is “desmosine”, a beautiful amino acid found abundantly in human skin, blood vessels, ligaments, and lungs.

Chemical synthesis of desmosine to diagnose lung disease

I determined to research desmosine after meeting Professor Gerard M. Turino MD, a key figure in chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) research, when I was researching at Columbia University in the US.

COPD is characterized by shortness of breath and reduced lung functionality due to permanent lung damage, often as a result of long-term smoking. While the number of COPD sufferers is increasing globally, early detection of the disease remains problematic.

Professor Turino told me that levels of desmosine, an amino acid found in elastin protein, increase in COPD patients with permanent lung damage—and that this increase could possibly be used for diagnosing COPD.

Since the body only generates a minute amount of desmosine, precise measurement requires the use of a synthetic form called an isotopically labelled compound The synthetic compound has the same chemical structure as naturally occurring desmosine, but a different mass. When it is added to urine or blood, it accurately indicates the desmosine content.

Professor Turino encouraged me to try creating this isotopically compound, which had yet to be created by anyone anywhere in the world. When I returned to Japan, I commenced with the research at once. After four years, I succeeded in creating the world’s first synthetic desmosine compound; since then, I have also managed to chemically synthesize many related chemical compounds including isotopic desmosine.

At present, I am preparing to carry out new research with clinicians and private enterprises aimed at using this synthetic desmosine to diagnose COPD and other diseases characterized by elastin degradation.

If you fail, try and try again

Another area of my research centers on extracting polyphenols from plants. Polyphenols exert antioxidants and anti-aging properties, which are used in cosmetics and health foods. If we can extract them more efficiently, we should be able to broaden their scope of applications.

Using deep eutectic solvents and other special solvents, we have developed methods for extracting polyphenols contained in the leaves of sweet potatoes, and polyphenols contained in “kabuchii”—a type of citrus fruit native to Okinawa.

The sweet potato polyphenols have been productized in the form of sweet potato leaf tea; for the kabuchii polyphenols, we have commenced joint research with cosmetics manufacturers with the aim of using them in cosmetics.

I begin my research by drawing up a plan of the process from start to goal—perhaps a better way of putting it is that I use existing information to “predict” what will happen as a scientist. Based on this plan, I experiment by mixing different ingredients and reagents in flasks and beakers.

However, these experiments never follow the path I predicted—80 percent of my experiments end in failure. It is painstaking, time-consuming work. Yet this is the standard way of carrying out experimental chemistry research—persisting with your experiments, and trying again and again.

In my research, I am motivated by a desire to benefit society. I hope that my research into desmosine will contribute to medicine, and that the techniques I have developed for extracting polyphenols from plant waste will contribute to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

I am also concurrently working on several other multi-year research projects. Going forward, I will continue devoting myself to research so that I can produce as many beneficial results as possible.

The book I recommend

“Kokoro”

by Soseki Natsume, Kadokawa Bunko

I first read Kokoro when I was a high school student. The final part of the story, which comprises a long confessional letter written by “Sensei,” was astonishing. I wish to astound the world with a similarly jaw-dropping narrative arc in my research, too—this is something I think about all the time.

-

Toyonobu Usuki

- Professor

Department of Materials and Life Sciences

Faculty of Science and Technology

- Professor

-

Professor Toyonobu Usuki obtained BS, MS, and PhD from the Department of Chemistry, Tohoku University. After working as a postdoctoral scientist at the Department of Chemistry, Columbia University, he was joined at the Department of Materials and Life Sciences, Sophia University as an assistant professor. He was appointed as a full professor in 2021.

- Department of Materials and Life Sciences

Interviewed: June 2023