In the Faculty of Human Sciences, Professor Minoru Sawada continues to study future curricula and instruction, aiming to redress educational inequality related to family background. He considers it important to visit schools in person to hear what students and teachers have to say, and then incorporate their voices in policy.

Children who attend public schools have a wide range of backgrounds in Japan. Some are socially disadvantaged. There are some who are caring for sick or elderly relatives, some whose parents are rarely at home, some who cannot help working part-time to earn a living, and some who are victims of abuse.

Focusing on the future shape of public education, my research explores what is inclusive education which will enable everyone to learn to their full potential, with no one left behind.

Exploring student-led learning

I specialize in the field called “critical education.” This discipline focuses on the various power relations and inequality issues associated with education, and has, from both theoretical and practical perspectives, produced a growing body of analysis into these issues, formal objections to socially unjust educational environments, and proposals aimed at correcting and transforming these conditions.

Many people can accept the curricula and instruction they encounter at school as a matter of course, but this is difficult for some children to. Instead of prioritizing any given curriculum, we need to reexamine the programs and spaces found in our schools, from the point of view of the children who encounter them.

This is why it is important for me to make onsite visits to schools. I often go to schools to observe classes or interview teachers. I have recently visited a couple of public high schools that are conducting their own unique initiatives. Those schools have café-like spaces on their premises where students can freely come and go during lunch breaks and enjoy free tea and snacks while having a casual and fun time. There are some students who live in disadvantaged circumstances and find it hard to come to school. A poor attendance record can force them to drop out before graduating, diminishing their chances of finding a job. The inclusive café spaces are part of the school’s effort to encourage these students to attend.

Sometimes, I volunteer at these cafés and talk with the students. Maybe it’s the relaxed environment, but the students sometimes open up about themselves. Once, a student said, “Hey, do you know where I got this scar?,” and if teachers or school employee can respond in a way that recognizes their struggle, if we were to say, “It must be tough, but it’s amazing that you’re still coming to school,” it can help the child realize that they do deserve praise, they are trying. A little confidence boost like this can awaken their desire to learn.

As schools change—and teachers change—so do the lives of the children.

There is objective data showing that a child’s future is largely determined by their place of birth and family income. It is crucial for teachers to take this fact into account. On the other hand, this is purely based on probability and should not be interpreted as fatalism. Even if changes in the structure of society are slow, as schools change—and teachers change—so do the lives of the children who study there. It is possible to for parts of the chain of inequality in school education to be broken, but that cannot be done by schools alone.

On top of their busy workload, teachers in Japan receive very little administrative and clerical support. Japan is among the bottom quarter of countries that spends the lowest level of education expenditure as a share of GDP across OECD countries. Since educational issues are closely tied to national policy, part of our roles as researchers is to connect national policy with the classroom. We also need to share information through different channels so we can re-evaluate the teacher’s working environment. I consider it my job is to both support the learning of individual children in schools, and to take action to reflect even only a little of the results of this research in national policy.

The book I recommend

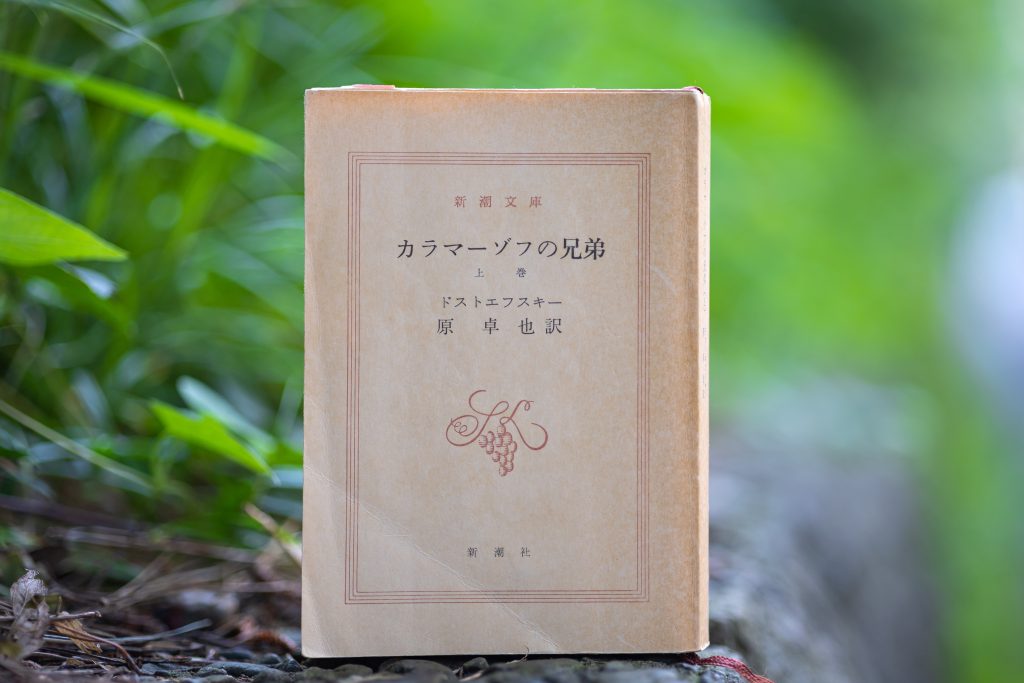

“The Brothers Karamazov”

by Fyodor Dostoyevsky; Japanese translation by Takuya Hara, Shinchosha

This book inspired me during my high school days; and I re-read it as a graduate student. A less than voracious reader, I think the reason I persevered with this novel—even writing out a genealogy of its characters— is because it portrays what it means to be truly human, or human beings full of contradictions.

-

Minoru Sawada

- Professor

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Professor

-

Graduated from Nagoya University, School of Education, Department of Education, and received his M.A. and Ph.D. in International Development from the university’s Graduate School of International Development. Worked as an associate professor at Nagoya Women’s University, Department of Childhood Education, Faculty of Literature and Sophia University, Faculty of Human Sciences, before assuming his current post in 2015.

- Faculty of Human Sciences

Interviewed: May 2022