Professor Manabu Haga of the Faculty of Human Sciences researches culture and religion and, at present, is particularly focused on Japanese festivals. Traditional Japanese festivals are organized by local communities; in contrast, modern-day festivals are linked by shared interests. But what, exactly, is the nature of these modern-day festivals, and how did they come about?

Sociology is a field of study that focuses on humans and society. Societies consist of clusters of human relationships, and we humans are influenced by these relationships in various ways. Individuals are fashioned by systems created by people of the past, and these individuals then work together with other individuals to create new societies; this cycle is continually repeated. Sociology entails researching the conditions and composition of such societies.

Sociology covers a broad range of topics, and I specialize in culture and religion. Culture and religion are extremely important to understanding what it is to be “human.” In contrast to other animals, humans live in safety and have plenty to eat—and simply being able to reproduce is not enough to satisfy us. Humans are liable to feel dissatisfied even if they possess everything they desire; on the other hand, humans can also find meaning and experience happiness even if they want for many things and appear at first glance to live in hardship. In truth, humans are strange creatures, and I believe that culture and religion are key to understanding the human condition.

Modern-day festivals are attended by people with shared interests

At present, I am chiefly focused on festivals. But, rather than traditional Japanese festivals, my primary sphere of interest is the modern-day festivals that have become popular in recent years. In ancient times, Japanese festivals were rooted in their localities, and they were organized by locals for the advantage of locals. These festivals can be thought of as “linked by geography.” On the other hand, in recent years another type of festival has become popular, particularly among younger people; people voluntarily form groups according to common interests or concerns, and these groups attend festivals around the country together. These festivals can be thought of as “linked by interest.”

A representative example of this latter type of festival is the Yosakoi Festival, which originated in Kochi Prefecture but is now held in various regions across the country. In the traditional Japanese festival dance known as “bon odori,” participants must use prescribed songs and movements; in yosakoi dance, however, so long as participants hold percussive clappers and use elements of designated songs, anything goes. Some yosakoi dance teams use rap-type songs, while others dance in the Hawaiian “hula” style. This originality is a major part of yosakoi’s appeal.

Societal changes are a key factor behind the increasing number of such festivals across Japan. In modern-day society, a higher proportion of interpersonal relations are “linked by interest” than before; social networks have made it easier for people to promote their activities, while advances in transportation have made travel easier, too. In order to revitalize their communities, local governments actively promote such festivals—another major reason why they have spread across non-urban areas.

Making careful records of present-day festivals for future generations

Fieldwork forms the greater part of my research. Taking “seriously, steadily, and repeatedly” as my modus operandi, I attend as many festivals as I can, and speak with as many people as possible.

Things tend to appear natural and correct when you are a member of cultural and religious circles, in particular; but as a researcher, it is imperative I remain dispassionate and objective. Of course, it is also important to consider the feelings of participants, and to retain a sense of empathy. For example, it is impossible to see what dancers see and to feel their joy without dancing oneself—for this reason, as far as possible, I try and participate as well.

Large numbers of festivals have been cancelled over the past few years due to COVID-19. Festivals attended by groups who are “linked by interest” can find it difficult to reestablish themselves if they are cancelled even once—this process of reestablishment is something I research as well. I believe it is also one of my responsibilities to preserve careful records of present-day festivals for future generations.

The book I recommend

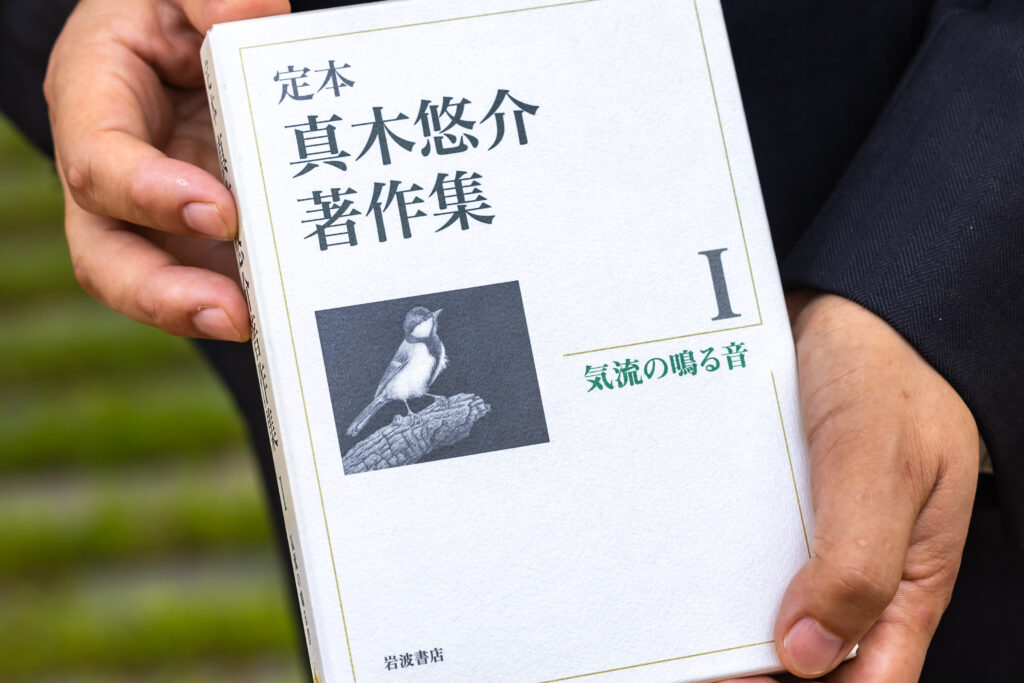

“Teihon Maki Yusuke Chosakushu I – Kiryu no naru oto”(Collected writings of Yusuke Maki, standard edition, I – The sounds produced by currents of air)

by Yusuke Maki, Iwanami Shoten

I read this book when I was about 20, and trying to choose which subject to study next at university. This was the book that inspired me to take up sociology. It taught me that events can be understood in more than just one way—that the way you see something changes according to your culture, religion, and other social factors.

-

Manabu Haga

- Professor

Department of Sociology

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Letters, The University of Tokyo. He completed his doctoral coursework at the Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo, and he received his M.S. in Sociology. After working as a teaching assistant at the Tokyo Gakugei University Faculty of Education, and as a lecturer and then as an assistant professor at the Sophia University Faculty of Humanities, was appointed to his current position in 2006.

- Department of Sociology

Interviewed: June 2022