Understanding Healthy and Happy Expectancy in Former Soviet Countries

Researchers compare the health situation in Russia and Central Asian countries using a multifaceted approach to health.

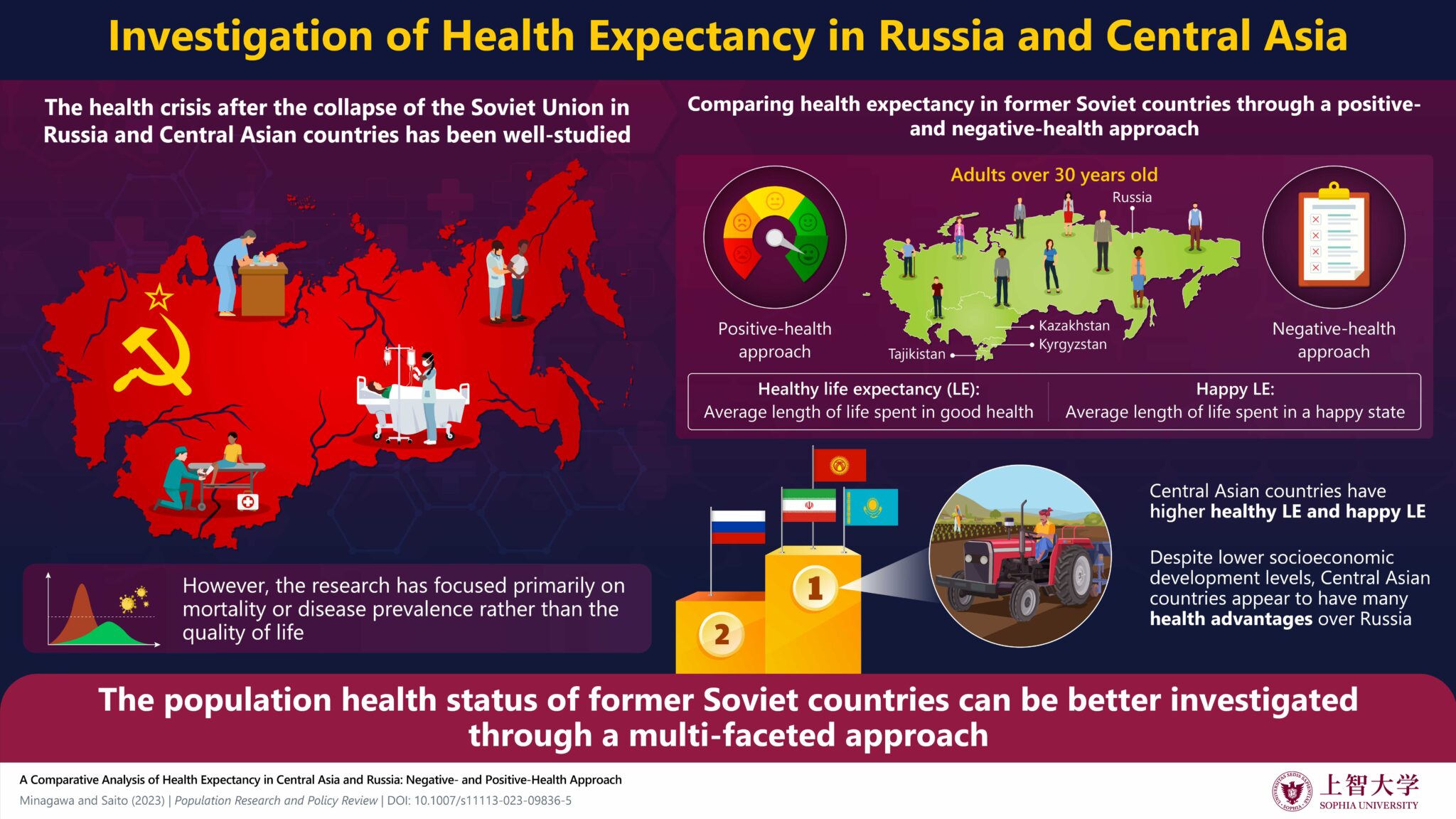

Although the mortality crisis following the collapse of the Soviet Union has been the subject of intense research, most research has only focused on negative aspects of health, such as disease prevalence. Recently, researchers from Japan compared health expectancy in Russia and Central Asian countries from negative and positive perspectives. Their findings reveal significant differences in health and happiness between these nations and highlight the importance of using a more multidimensional definition of health.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the start of a period ripe with political, economic, and societal changes. In many former Soviet countries, these abrupt and turbulent transformations posed massive challenges to healthcare systems. Together with spikes in job losses and economic hardships, this led to a steep increase in mortality rates that would later come to be known as the “post-Soviet mortality crisis.”

However, this crisis did not affect all former Soviet countries equally. In particular, former Soviet countries in Central Asia, which include Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, saw a notably smaller rise in mortality than Russia. Unfortunately, while there have been extensive studies on the mortality crisis, not much is known about the quality of life in former Soviet countries from a health-related perspective.

To address this knowledge gap, Associate Professor Yuka Minagawa of Sophia University and Professor Yasuhiko Saito of Nihon University, both in Japan, set out to gain a better understanding of health in former Soviet countries. “Past research has limitations in that most studies focus only on negative aspects of health, i.e., the prevalence of diseases, leaving it an open question to what extent a positive dimension of health, such as happiness and life satisfaction, contributes to the population’s overall health status,” explains Dr. Minagawa, “Moreover, the high prevalence of chronic illnesses has become a major public health concern in this region, making it critical to assess not just the length of life but also the quality of life lived.” This study was published online in the journal Population Research and Policy Review on November 21, 2023.

The researchers employed a theoretical framework proposed in 1996 by the Dutch sociologist Dr. Ruut Veenhoven, who dedicated much of his work to understanding happiness from a sociological perspective. Based on this framework, the researchers adopted a multifaceted approach to analyze health by estimating two types of health expectancy: healthy life expectancy (LE) and happy LE. The former refers to the average length of life spent in good health, corresponding to the “negative” dimension of health. In contrast, the latter refers to the average length of life spent in a happy state, which reflects a “positive” dimension of health.

The study primarily centered around comparing the health expectancy values between Russia and the Central Asian nations of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. The researchers gathered data from two sources: mortality data published by the World Health Organization and self-reported health and happiness data from the World Values Survey.

The findings revealed a situation that appears to be counter-intuitive. “We found that populations in Central Asian countries have significantly higher healthy and happy LE when compared to their Russian counterparts,” says Dr. Minagawa, “This suggests health advantages in Central Asian countries over Russia, despite their lower levels of socioeconomic development.” While the healthy and happy LE values among Russians have been increasing over the past decade, the gap between Central Asian countries and Russia is still significant. For example, men in Central Asia can expect to live about 38 years in a happy state and 65 years in good health, whereas for Russian men, these values drop to 33 and 45 years, respectively.

Interestingly, this work challenges our understanding of health and raises questions about what may be contributing to the healthier and overall happier lives of people in Central Asian communities compared to those of Russians. “This study has an important bearing on the definition of health,” remarks Dr. Minagawa, “Health tends to be measured by the presence of disease but, as stated in the definition proposed by the World Health Organization, a better understanding of health requires research focusing on both its positive and negative aspects.”

Moreover, the general population health in Russia could start declining due to the Russia–Ukraine conflict. Thus, this study underscores the need to strengthen welfare policies that contribute to the well-being of Russians. Hopefully, the health situation in former Soviet countries will improve, helping mend the wounds left by history.

Reference

- Title of original paper: A Comparative Analysis of Health Expectancy in Central Asia and Russia: Negative‐ and Positive‐Health Approach

- Journal: Population Research and Policy Review

- DOI: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11113-023-09836-5

- Authors: Yuka Minagawa1 and Yasuhiko Saito2

- Affiliations: 1Sophia University

2College of Economics, Nihon University

About Associate Professor Yuka Minagawa from Sophia University

Dr. Yuka Minagawa holds a B.A. degree from Sophia University, an M.A. degree from Harvard University, and a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin. She is currently an Associate Professor at Sophia University, where she researches the topics of social demography, health and aging, and the socioeconomic transition from communism in East Central Europe and the former Soviet Union. She is particularly interested in theories linking social environments and health. She has published over 17 research papers on these topics.

Funding information

This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 20K22150).

Media contact

Office of Public Relations, Sophia University