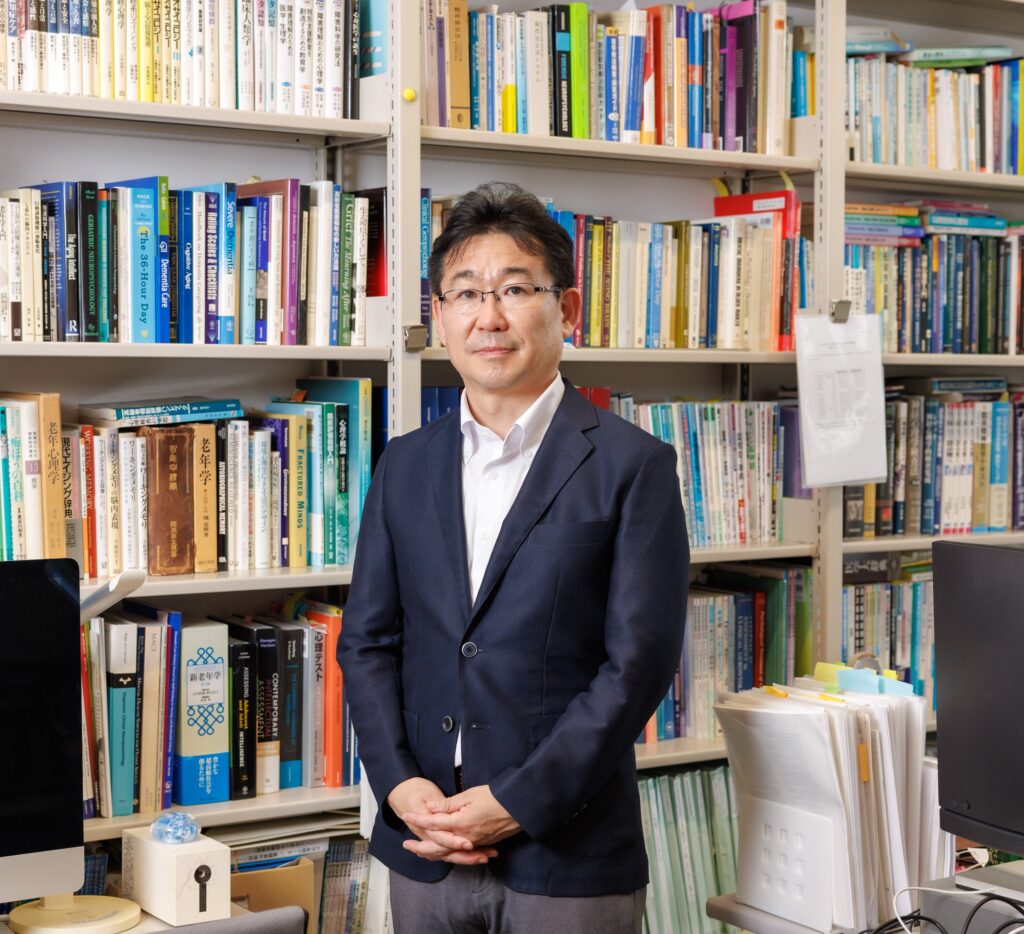

As Japan’s population ages, so the number of patients with dementia is increasing. Here, Professor Osamu Matsuda of the Faculty of Human Sciences discusses the role psychology can play in preventing memory and judgment declines, and in enabling patients to live well with dementia.

People tend to associate dementia with an inability to do anything, and with a loss of self-awareness. However, many patients in the early stages of dementia can continue to work or do household tasks, despite experiencing forgetfulness.

It is also possible to delay the progress of dementia through medical treatments and through the provision of care. Nevertheless, many people continue to associate early detection of dementia with early despair.

The capabilities of patients with dementia

I am a certified public psychologist, and it is from this perspective that I research dementia, with a particular focus on neuropsychological tests and psychological support. In Japan, Alzheimer’s disease causes dementia in close to 70% of patients; depending on how far the disease has progressed, some cognitive functions are prone to decline, but others are preserved.

For a given patient, we assess their cognitive functions through neuropsychological tests. We determine what they can continue to do in the same way as before, and what they can no longer do, and ascertain what solutions are required. Our goal is to encourage patients to change the way they do various everyday tasks, and to encourage family members and specialized caregivers to revise the way they provide support.

In the 21st century, an increasing number of patients are undergoing diagnostic examinations in the very earliest stages of dementia onset. It is important for patients to undergo neuropsychological tests and assessments in addition to medical tests; but with conventional tests, it can be difficult to diagnose early-stage dementia.

For this reason, we are developing new testing methods that take modern understandings of dementia into account, and creating Japanese-language versions of new testing methods from overseas.

Dementia is not a life-ending disease

In my research, I am also particularly focused on finding ways to reduce the anxiety and distress patients feel due to a decline in their cognitive functions.

I am working together with physicians who specialize in dementia to develop psychological exercises that help maintain cognitive functions, and programs that enable patients with dementia to interact with others and experience the joy of accomplishment.

Of course, I am involved in verifying the effects and effectiveness of these exercises and programs, too.

Patients with dementia are frequently reminded by those around them that “they have forgotten again” and, gradually, there is an increase in the number of things they can no longer do. They are therefore apt to lose confidence, and many of them seek to avoid interacting with other people.

Nevertheless, by setting themselves goals and working with other people, patients with dementia can experience first-hand that they still possess the capacity to accomplish things.

My students regularly participate in a “dementia-prevention cafe,” where elderly citizens who do not have dementia gather to exercise, play mahjong, and even sing karaoke. I myself also participate, if I have no lectures or conferences.

This cafe seeks to encourage the elderly to exercise their brains and express their emotions while having fun, and thereby prevent a decline in their cognitive faculties.

My goal is to eradicate the notion that dementia spells the end of normal life. Patients, often the most distressed when there is a diagnosis of dementia due to their own daunting associations of the diseases, should understand that it is nothing to be embarrassed about; nor is it the result of their habits.

As we age, dementia can affect anyone, and as a society we must find a way to live hand-in-hand with the disease—this entails both treating and supporting those who have dementia, and working to prevent cognitive decline in those who do not.

Certified public psychologists are not capable of “curing” dementia. However, we are able to stand together with patients and face up to the distress and anguish they suffer.

Reducing obstacles in their daily lives, ensuring they interact with other people, and increasing feelings of joy and accomplishment can help impede the progress of dementia. And this, I believe, is the role that psychology has to play.

The book I recommend

“Kyo no ronenki chiho chiryo”(Modern methods of treating old age dementia)

by Masaaki Matsushita, Kongo-shuppan

This book taught me that psychological factors contribute to differences in patients with dementia—such as why some have a tendency to wander about, but others do not. There was a time when I doubted whether psychology could be of use in treating illnesses that result in physical changes to the brain. This was the book that showed me the way forward.

-

Osamu Matsuda

- Professor

Department of Psychology

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Professor

-

Professor Osamu Matsuda received his Ph.D. in health science from The University of Tokyo Graduate School of Medicine in March 1996. After working as an assistant, lecturer, assistant professor, and then associate professor at the Department of Educational Psychology, Tokyo Gakugei University, he was appointed to his current post in April 2017. Matsuda has been Dean of the Graduate School of Human Sciences since April 2021.

- Department of Psychology

Interviewed: July 2023