Are the rights of foreign residents living in Japan truly protected? Masako Tanaka, Professor at the Faculty of Global Studies, and an expert in immigrant issues from the perspectives of gender, health, and education, discusses the issues on immigrant women’s reproductive health and rights.

My research focuses on immigrant women’s reproductive health. While research in this field has mainly been conducted by health professionals, my aim is to analyze this topic from a human-rights perspective and discuss structural barriers in Japan.

Technical intern trainees also have the right to give birth in Japan

Many immigrant women who come to Japan to work or study are women of reproductive ages between 15 and 49. They should not receive unfair treatment for becoming pregnant. Furthermore, if they are workers, they should be entitled to maternity leave.

There has been a considerable number of cases of trainees in the Technical Intern Training Program being forced to sign pledges that require them to return to their home country if they become pregnant, based on the rationale that, as interns, they are not permitted to bring family with them to Japan. The notion that their contract will be terminated or that they will be forced to return to their home country if they become pregnant is more than just a presumption; it is reality. These dire circumstances extend to international students as well. International students are not subject to labor protections, which means that absence due to pregnancy or childbirth can lead to dismissal from their school and termination of their residential status.

Many of these women have gone into debt to cover the cost for coming to Japan. The prospect of employment termination or school expulsion is terrifying. They have no one to go to if they get pregnant, and as a result, many have given birth on their own without medical supervision or checkups. In the worst case, women have even been arrested on charges of abandoning stillborn babies.

The inability for immigrant women to exercise the rights they are entitled to is a major issue from both domestic and international perspectives.

Behind unintended pregnancies is a lack of contraceptive options

I conducted an online survey of more than 500 foreign residents in Japan. Participants were men and women from five countries: Vietnam, Nepal, Myanmar, Indonesia, and China. The survey revealed a shared disappointment among the participants: they assumed there would be more contraceptive options and health care services in Japan than in their home countries; but reality paints a different picture.

The main form of contraception in Japan is condoms. Other contraceptive options have barely gained traction. Oral contraceptives are prescription drugs and not covered by the national health insurance for contraceptive purposes. In Nepal, all contraceptives and contraceptive devices are generally free of charge at government health facilities and those purchased at pharmacies range from a few tens to a few hundred yen.

Until recently, the only abortion option in Japan was surgery, which costs several hundred thousand yen. The oral abortion pill was approved in April 2023, but the cost is essentially the same as surgery because the woman must remain in the hospital; and spousal agreement is still required. There is even a charge in the criminal code for illegal abortions.

Poor access to contraception and abortion is not a problem limited to immigrant women. Incidents of babies dying due to medically unsupervised births is also prevalent among Japanese youth. It is an issue close to home for everyone and needs to be reassessed systemically. I have shared my research findings with legislators and have been quoted at Diet committee hearings. There are also more newspaper articles covering the issue, which has prompted the Immigration Services Agency to launch its own investigation into the subject.

The issues affecting immigrants will never be resolved if Japan’s politics do not change. However, immigrants do not have the right to vote. Only Japanese voters can change politics. This is an important truth we must not forget.

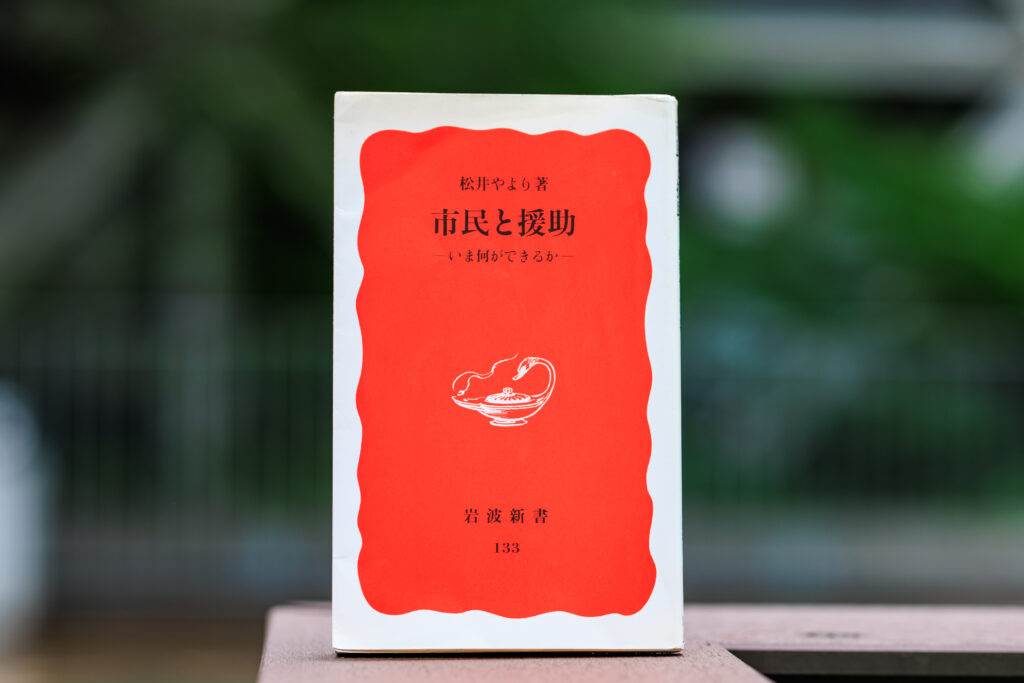

The book I recommend

“Shimin to Enjo – Ima Nani ga Dekiru ka”(Citizens and Aid – What Can Be Done?)

by Yayori Matsui, Iwanami Shoten

Published in 1990 at the end of the bubble economy, this book details what actions should be taken by the citizens of Japan, an economic superpower. I was in my second year in the workforce when it was published. Inspiring me to work in the field of international cooperation, the book left such a strong impression on me that I quit my job and left for the UK to pursue my studies.

-

Masako Tanaka

- Professor

Department of Global Studies

Faculty of Global Studies

- Professor

-

Masako Tanaka obtained her BA from Kobe University. She obtained her MA in Gender Analysis in Development from the University of East Anglia, before obtaining her PhD in Development Studies at Nihon Fukushi University. As a development practitioner, she has worked in Japan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Ghana with JICA, the Japanese Red Cross Society, the Netherlands Organization for Development (SNV), and other NGOs. She returned to Japan in 2009. Following work with Bunkyo Gakuin University from 2010, she assumed her current post at Sophia in 2014.

- Department of Global Studies

Interviewed: June 2023