Professor Hiroyuki Tani at the Faculty of Foreign Studies researches the Latin American economy with a focus on Mexican agriculture. Here, he speaks on the light and shadow cast on Mexican agriculture by the sharp rise in fresh vegetable exports to the U.S. under trade liberalization.

My research field is the Latin American economy, and my main focus is on the relationship between Mexican agriculture and its economic development process. We now see more and more fresh produce from Mexico, like avocados, asparagus, and pumpkins, among others, in our nearby supermarkets. One of the key factors that spurred large-scale vegetable export from Mexico was the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which came into force in 1994. In trade statistics, fresh vegetable exports from Mexico to the U.S. have rocketed eight times in the thirty years since 1990. This brought large transformations to Mexican agriculture.

Fresh vegetables to the U.S. market: opportunities seized by Mexican producers

Trade liberalization casts both light and shadow. When Japan, for example, joined the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) in 2015, it was said that “Inexpensive produce from foreign sources is going to put Japanese farmers out of business.” Mexico has also experienced massive imports of inexpensive corn from the U.S., and in fact, it resulted in a large hit to small farmers. When I visited Mexico, many locals expressed concern about the situation, saying that it was almost impossible to continue farming with the falling prices of their products and the soaring costs of the inputs.

On the other side of the coin, there are producers who have seized upon trade liberalization as an opportunity. Vegetable and fruit production is typically labor-intensive, and in the U.S., the labor costs are extremely high: the hourly wage there is even higher than a full day of pay in Mexico. This means that, even with shipping fees, it often costs less to import produce from neighboring Mexico than to produce vegetables within the U.S.

As I have just said before, NAFTA has been one of the key elements of the exponential increase in fresh vegetable exports, but I also have to point out that it is important as well that Mexican producers have equipped themselves with fully refrigerated warehouses, packing plants, and trailers. The fact that the government constructed highways and other infrastructure necessary to deliver the produce to U.S. consumers has also been a significant factor. Recent years have also seen a dramatic increase in the shipping of easily perishable leafy vegetables like spinach and lettuce, which previously were considered unsuitable for export.

As part of my field research, I visited a greenhouse tomato production company. They harvested tomatoes at a pace of two and a half times per year, regardless of the season. It was also interesting to see that they had realized low agrochemical cultivation because, in the greenhouses, they can control pests and diseases more easily. The company planned its production cycles based on orders they got directly from supermarket chains in the U.S. and Canada, where the reputation of “safe vegetables” is crucial in marketing their products. Though trade liberalization created an adverse climate for many smallholders, many producers could take this change as an opportunity for their new business. It is necessary to look at both the light and the shadow cast by free trade.

Understanding more deeply communicating with Mexican people in their language

There are many researchers attempting to shed light on the changes in Mexican agriculture from an economic perspective. Of course, that endeavor is also important. However, I want to understand the Mexican economy as a part that comprises Mexican people’s life. What characteristics does Mexico have as a region? Which logic urges Mexican people to act when they confront a certain situation? These are the basic questions that lie under my research projects. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I used to visit twice a year, mainly to interview agricultural producers. Reading academic papers and interpreting statistical data is definitely essential, but I believe that it is important as well to grasp first-handed data on-site to know more about the current state of Mexican agriculture.

To do this kind of research, the ability to communicate in the language spoken in the field is indispensable. Listening to what the people are speaking in their own language allows me to understand on a deeper level the situations they have experienced and are experiencing, as well as their complaints and hopes. One of my mission is to transmit what I learned in this manner from Mexican people to Japanese society as far and deep as possible. Japan and Mexico share a commonality: these two countries have deep ties with the United States, and we cannot think of our political and economic lives disregarding it. By looking at how Mexican farmers and agricultural producers reacted to the change in trade policy and how they acted to confront the new situations, we would be able to draw some lessons from their experiences. I hope that, in some small way, my writings on Mexican agriculture can benefit Japanese farmers.

The book I recommend

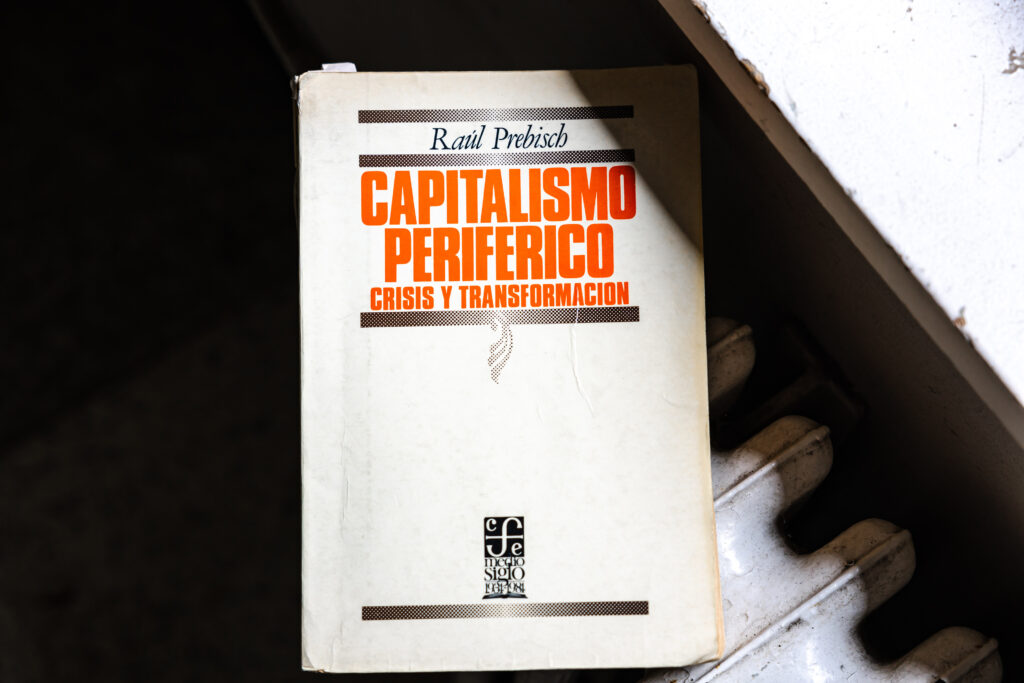

“Capitalismo periférico: Crisis y transformación”

by Raúl Prebisch, Fondo de Cultura Económica

I first learned about this book by Argentinian economist Raúl Prebisch in the first session of a Development Economics seminar when I was in my third year at university. It has captured my attention since then. I encountered a copy in a bookshop in Mexico a few years later when I was a graduate student, and after struggling with it for four more years, I got finally able to write an academic paper about his economic thoughts developed in this book. It always reminds me of the importance of persevering in working on it, even if you do not understand it immediately.

-

Hiroyuki Tani

- Professor

Department of Hispanic Studies

Faculty of Foreign Studies

- Professor

-

Professor Hiroyuki Tani graduated in 1988 from the same Department where he now teaches, and completed the Doctoral Program in International Relations at Sophia University in 1994. He has been teaching Spanish and Latin American economics at the Department of Hispanic Studies at Sophia University since 1998.

- Department of Hispanic Studies

Interviewed: July 2022