A country’s criminal law defines which actions are crimes, and their corresponding punishments. Here, Professor Ryosuke Terunuma of the Faculty of Law, an expert in complicity, discusses the significance of researching criminal law in Japan.

Criminal law studies is a field concerned with those laws that relate to crimes and punishments. My own area of expertise is “complicity,” a branch of criminal law that deals with crimes committed by multiple persons.

Japanese criminal law refers to a person who commits a crime as the “principal.” When multiple persons are found to have committed a crime together, they are punished as “co-principals.” There are also distinctions between “inducers,” who induce a person to commit a crime, and “accessories,” who provide assistance to the principal perpetrator. The law has provisions for inducers and accessories to receive lighter penalties than a principal.

Group responsibility versus individual responsibility

In practice, however, legal distinctions can be hard to apply. In recent years, much discussion in Japan has focused on the complicity of individual members of crime groups committing money transfer scams – or “furikome sagi” as it is called in Japan.

These groups consist of multiple actors, each of whom fulfills a different role: an “ukeko” (lit. “the receiver”), is tasked with collecting money from victims; a “dashiko” (lit. “the withdrawer”), is tasked with using bank cards to withdraw money from cash machines.

Consider a situation where an ukeko, acting on instructions from a boss, collects money from a scammed victim. The ukeko does not know the victim’s identity, and is carrying out this crime solely as a means of earning some money. Is it right for this ukeko to be judged a principal, equal to the boss who planned the entire fraud, and who actually duped the victim?

In recent years, situations where the ukeko has not actual received payment, the boss uses personal information to trap the ukeko, or where the ukeko is used as a sacrificial pawn have further complicated the issue.

Child abuse cases present an altogether different, yet similarly difficult set of circumstances. If violence perpetrated by the father results in the death of his child, and the mother does not prevent such violence, should she always be punished to the same degree? If the mother was also a victim of domestic violence at the hands of the father, what then?

In Japan, the idea of group responsibility among criminals is deeply ingrained. Even today, Japanese society tends to deal with a group collectively rather than judging each of its members individually—if a sports team loses a match, for example, then all members of the team might have to run 10 laps of the pitch.

There are clear parallels here to the notion that, because a group was acting together, each of its members ought to be subject to the same punishment.

The importance of persuasive reasoning

Every person will respond differently to the question: “what is justice?” In criminal trials, too, it can be formidably difficult to reach a verdict that is considered reasonable by all parties.

Accordingly, it is crucial that those responsible for imparting judgments adopt lines of reasoning that have the power to persuade even those who hold different opinions. Indeed, persuasive reasoning is a critical skill for all students of law, no matter which branch they intend to specialize in.

Research into criminal law studies provides diverse choices when it comes to actual trials. In Japan, our system of “saiban-in”—or “lay judges”—requires ordinary citizens to contribute to a judgment within a limited period of time; we have a duty, therefore, to ensure our research is easy to understand. In fact, a similar care is required when teaching classes at university.

A criminal trial not only impacts the lives of defendant, but also has far-reaching effects on the victim, the victim’s family and neighbors, and society as a whole. As researchers, it is our duty to focus on points where law and society intersect and, where necessary, make proposals that lead to amendments to laws.

The book I recommend

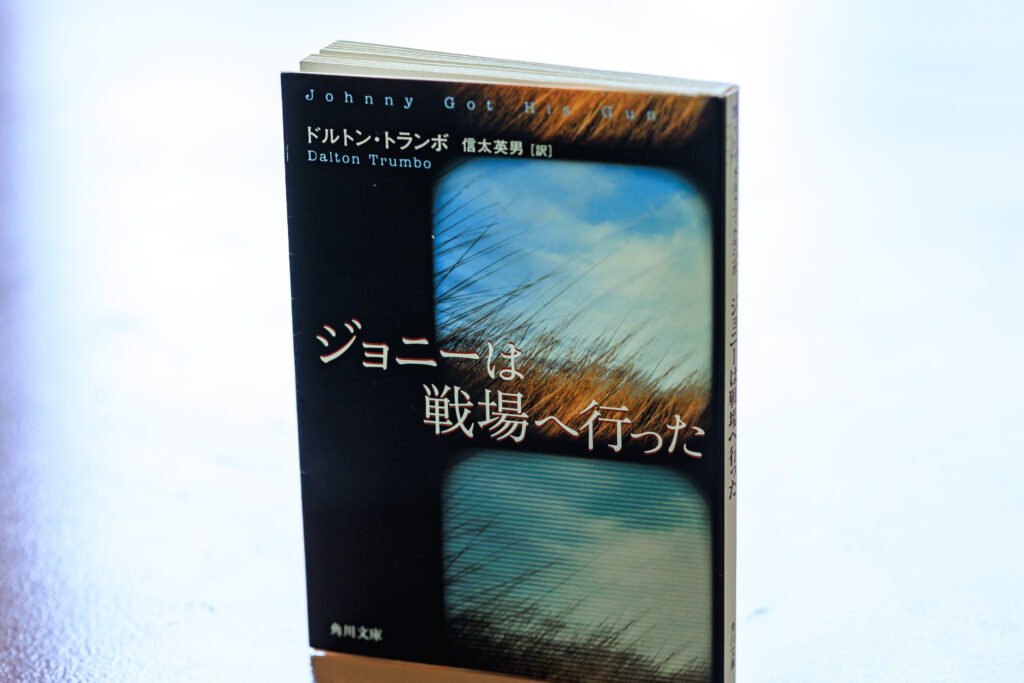

“Johnny Got His Gun”

by Dalton Trumbo, Japanese translation by Hideo Shida, Kadokawa Bunko

This book served as the basis for the film of the same name, and the heavy metal band Metallica featured a scene from the film in their music video for “One.” I remember the shock I felt when I read the book as a student. The despair experienced by Johnny, who loses his arms and legs and most of his face, forced me to see society from a new perspective.

-

Ryosuke Terunuma

- Professor

Department of Law

Faculty of Law

- Professor

-

Professor Ryosuke Terunuma graduated from the Department of Law, Faculty of Law, Keio University, and received his Ph.D. in Law from the university’s Graduate School of Law. After working as an assistant professor at the Faculty of Law, Okayama University, and as an associate professor specializing in the legal profession at the Graduate School of Business Sciences, Tsukuba University (Tsukuba University School of Law), Terunuma was appointed to his current position in September 2012.

- Department of Law

Interviewed: June 2023