Professor Akihiro Yamamoto of the Faculty of Humanities specializes in classical Japanese literature. He specializes in “shakkyoka,” a form of waka (Japanese poetry) that includes Buddhist elements, which was popular from the late Heian period (794–1185) to the beginning of the Kamakura period (1185–1333). But what impact did shakkyoka have on Japanese poetry?

I am a researcher of classical Japanese literature; in particular, I specialize in waka from the end of the Heian period to the beginning of the Kamakura period. Waka is an extremely ancient form of verse; the first waka is said to have been composed by the mythic god Susanoo-no-Mikoto, and over the centuries it has played a central role in Japanese literature.

Common subject matter for waka include the four seasons, love, journeys, and grief; in my research, however, I concentrate on a form of waka called shakkyoka, which incorporates Buddhist elements.

From the end of the Heian period to the beginning of the Kamakura period, reclusive monks such as Saigyo Hoshi, Kamo no Chomei, and Yoshida Kenko composed various waka and essays. Renouncing secular life, they observed the world at one remove. I believe their writings show us how we can live freer lives.

Saigyo, Jakusen, and Jien: The appeal of the waka by three ordained monks

I have a special interest in three monks: Saigyo, Jakusen, and Jien. Saigyo was an accomplished samurai who worked as an imperial guard for the retired Emperor Toba, but he chose to become a monk at the age of 23. His verse is characterized by its wide-ranging subject matter—not only love and the four seasons, but also the lives of ordinary people—and his writings had an immense influence on society.

Jakusen was a friend of Saigyo’s, but few of his waka remain. He is perhaps best known for his Homon hyakushu, a collection of waka inspired by Buddhist scriptures. In this work, he imbues Buddhist teachings with Japanese artistic sensibilities, all within the traditional waka frameworks of the four seasons and love. Homon hyakushu had a significant impact on the acceptance of Buddhism in Japan.

Jien was born into one of the Five Regent Houses of powerful Japanese aristocrats. He was an eminent monk who rose through the ranks; he became head of the Tendai school of Buddhism, as well as a “gojiso”—a monk who prayed for the protection of the emperor. He yearned to become a recluse and lead a free life in the same way as Saigyo, but he was unable to resist the path ordained for him due to his regent lineage.

His most famous waka are prayers for the country and the emperor; however, his poems also reveal his inner conflicts, and teem with emotions that modern-day readers can sympathize with.

Inter-disciplinary research on Shakkyoka, including Buddhist studies, philosophy and history

There are few researchers who specialize in shakkyoka. However, it is my belief that shakkyoka played a vital role in enabling waka to endure unchanged over the course of many centuries. Waka were composed in different structural forms, they were used for proselytizing and for praying, and they spread to every corner of society.

Waka are a form of song and, for this reason, they are extremely approachable. Precisely because they are songs, waka intuitively evoke visions of paradise, provide consolation, and inspire courage. In the same way as the songs of today, waka have persisted and adapted over time. I believe this is why waka have continued to be one of Japan’s most important forms of culture.

A great deal of waka has yet to be translated. It is the role of researchers of classical literature such as myself to enable them to be read. I approach each poem individually, and analyze it objectively: I take care to ensure my emotional response does not affect my interpretation, and I consider the feelings of the composer and the circumstances in which the waka was composed.

Eliminating prejudice is important not only for researching literature, but also for our personal relationships. Shakkyoka are a form of waka, but they are also part of Buddhism—and they therefore pertain both to philosophy and to history as well. My goal is to take an inter-disciplinary approach to researching shakkyoka—an approach that incorporates philosophy and history.

The book I recommend

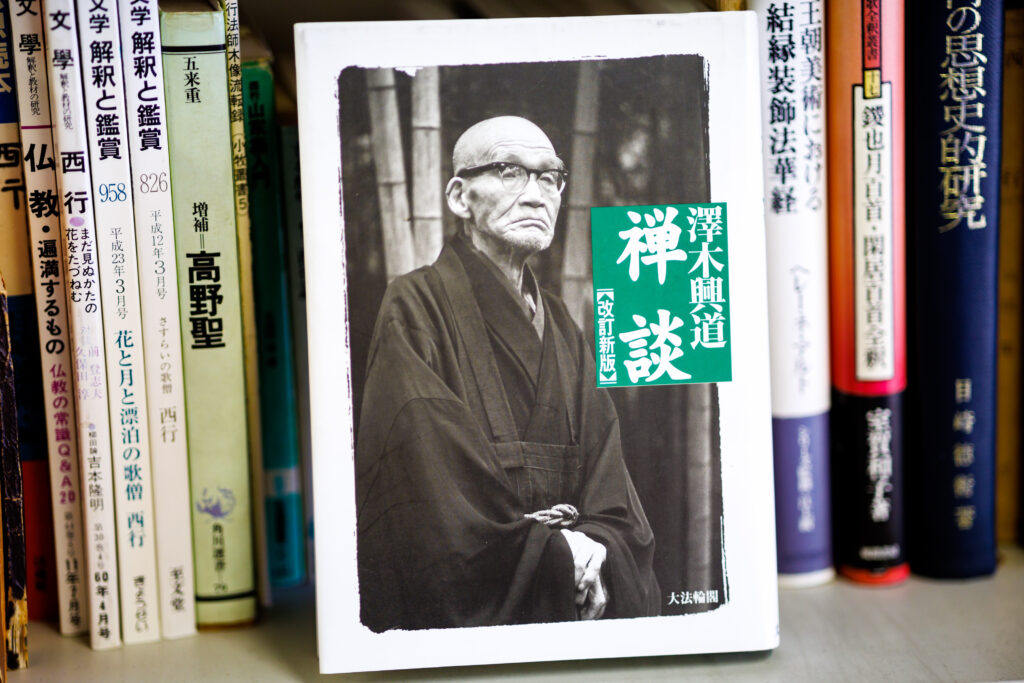

“Zendan”(Discussions of Zen Buddhism)

by Kodo Sawaki, Daihorin-kaku

I read this book about Zen Buddhism immediately after entering university. It contains a variety of Zen teachings, such as “if you can be satisfied with few desires, you will find peace.” It fundamentally changed my way of thinking, and sparked my interest in the relationship between literature and Buddhism.

-

Akihiro Yamamoto

- Professor

Department of Japanese Literature

Faculty of Humanities

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of Japanese Literature, Faculty of Humanities, Sophia University; received his Ph.D. in literature from the university’s Graduate School of Humanities. After working as a teacher at Gakushuin Boys’ Senior High School, as an associate professor at the Faculty of Literature, Taisho University, and as an associate professor at the Faculty of Humanities, Sophia University, he was appointed to his current position in 2022.

- Department of Japanese Literature

Interviewed: December 2022