Professor Kenta Kasai from the Graduate School of Applied Religious Studies undertakes research on the relationship between people and religion throughout history. He talks about his long-time research into the relationship between religion and self-help groups for alcohol addiction as well as training of attentive listeners at the graduate school and lifelong learning program.

Religious studies is often misunderstood as being a subject for religious people in some particular churches or temples. Actually, just as how biology is the study of observing living things and thinking about how they relate to humans, religious studies is the research field of observing religions and investigating and thinking about their relationships with people. Therefore, there are many researchers of religion who are atheists or agnostics.

In my 30-odd years as a researcher, I came to see religion as a framework for people to think about worldly matters, not as a dogma or a belief in the particular reality. So far, my research had been about how people in religion view their own weaknesses, and how we should live with religion. In particular, I focus on the theme of addiction recovery and religion.

Embarking on the path of research after being deeply shaken from listening to experiences of addiction

It all started at a documentary film screening held by an alcohol addiction self-help group – Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) —at the university where I first worked as a researcher. A self-help group is a gathering of people—each with some form of disability or problem—aimed at supporting each other to overcome difficulties. After watching the film, I listened in detail to the recovery experiences of the group members. Deeply shaken, I paid further attention to their words and brought this relationship into my research.

Many self-help groups are modeled after AA, which was established in the United States in 1935. Christianity has rituals of repentance and confessing a sense of sin and pain to priests, and self-help groups such as AA base their programs on Christianity’s activities and processes of recovery through facing weaknesses.

Looking at history, there had appeared various “remedies” for alcoholic addiction in the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries, but they came and went without becoming entrenched. This is in contrast to AA’s program, which is now practiced by more than two million people globally and referred in modern psychiatry textbooks as a standard treatment for addiction. However, even self-help groups like AA have a history of both trials and errors. When I published some research works about AA history due to my hope to learn from these trials and errors, it brought me joy to hear from people in recovery and medical workers involved in addiction cases that my work can also be helpful in empowering patients.

Teaching empathy with attentive listening training

As part of my research, I have also interviewed people who recovered from alcohol addiction. Their weakness—being blamed by others or blaming oneself— leads to drinking again. On the other hand, those who have recovered from addiction have found a way to face their own weaknesses. I hope to convey the voices of these recovered people, not just to those facing addiction but also to people who are depressed due to failures, through such universal message that it is possible to start life afresh.

In parallel with my research, I am also training attentive listeners at the graduate school and Sophia University’s lifelong education program, the Institute of Grief Care. Attentive listening means to listen to life stories with respect for others. The practices of attentive listening actually include many concepts originating from religions that have accepted diverse values.

The people studying at the graduate school and Institute of Grief Care include many medical professionals and adults who have experienced the loss of a close family member. Attentive listeners are required not only at medical frontlines but also in local communities, and I have high expectations on the roles these people will play. If there are attentive listeners nearby for people with problems, our society may also become more friendly and forgiving than it is now. I hope to go about research with the goal of achieving such a society.

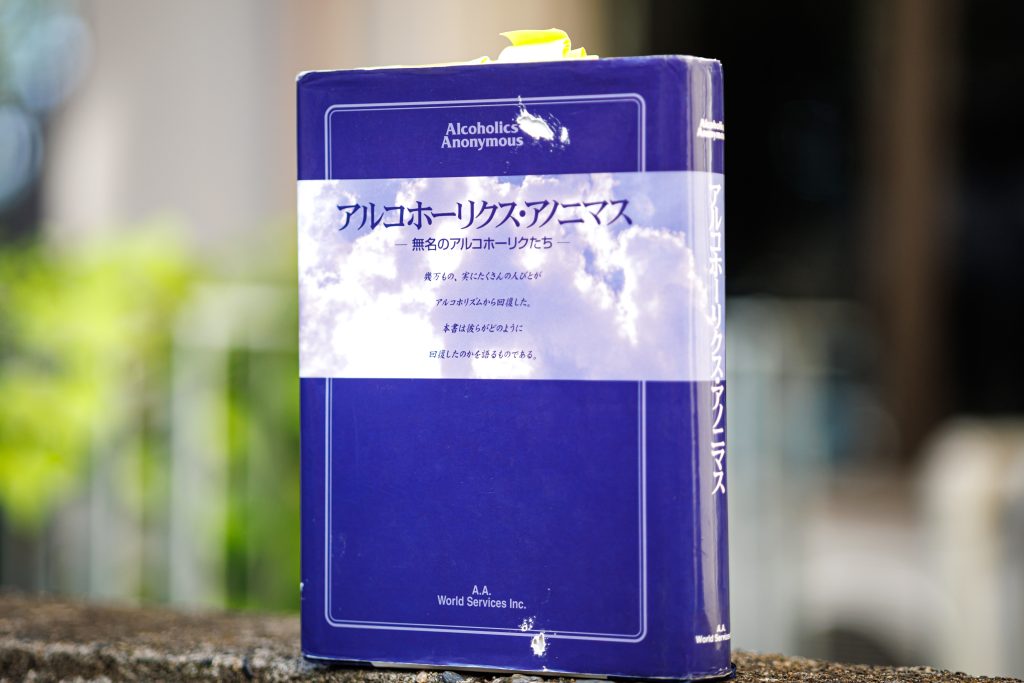

The book I recommend

“Alcoholic Anonymous”

by Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. (Japanese translation is also available by A.A. Japan General Service)

In this book, members of Alcoholics Anonymous talk about their authentic experiences regarding how to live with human weaknesses and failures that one wants to forget. I was inspired by the recovered addicts who accepted their weaknesses to live as their new selves. Original English edition of this book Alcoholics Anonymous can be obtained from online bookstore.

-

Kenta Kasai

- Professor

Graduate Program in Death and Life Studies

Graduate School of Applied Religious Studies

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Faculty of Letters, the University of Tokyo, and received his Ph.D in Religious Studies at the university’s Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences. He experienced several positions—such as a research fellow at the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, a research assistant at the Joetsu University of Education, a research fellow at the Center for Information on Religion, and project associate professor at Sophia University’s Institute of Grief Care—before assuming his current position in 2022.

- Graduate Program in Death and Life Studies

Interviewed: September 2022