Professor Kensuke Ueda of the Faculty of Law specializes in constitutional law, and its administrative aspects in particular. Here, he discusses the importance of considering how laws can be improved to make Japanese politics better; he also talks about his methods for identifying present-day problems and about the satisfaction he derives from his work.

When you hear the phrase “constitutional law,” for some of you it might bring to mind the articles of the Constitution of Japan; for others, it might evoke the three basic principles of the Constitution—sovereignty of the people, pacifism, and respect for fundamental human rights.

Less well known is that many laws and rules exist to ensure the implementation of these articles and principles, such as the Cabinet Law and the Diet Law. My research involves thinking about how to make the rules concerning the government better—this includes not only the Constitution of Japan itself but the laws and rules that relate to them as well.

I was moved to start researching this topic in the 1990s. Around this time, there was growing criticism of the bureaucrat-led rather than politician-led politics that prevailed in Japan, accompanied by increasing calls for political and administrative reforms.

I came to a realization: if it was true that bureaucrats had a significant influence on governmental policy-making, then perhaps the rules that governed our country made it easy for bureaucrats and hard for politicians to control Japanese law-making.

When I compared Japan’s Cabinet Law to that of the U.K., there was a stark contrast: politicians in the U.K. wielded great power. This motivated me to propose a form of law-making that would make it easier for the Prime Minister and his or her Cabinet to take control.

Is a “twisted parliament” in the interest of the Japanese people?

Today, control over governmental policy-making has shifted from bureaucrats to politicians; and this has cast a light on the composition of the Diet, which controls the Cabinet. One of the key roles of the Diet—and in particular the opposition factions—is to keep the Cabinet in check, and to ensure the Cabinet clearly explains its policy-making to the Japanese people.

In the past, however, we have had what we in Japan call a “twisted parliament”—when the ruling party holds a majority in the Lower House and the opposition a majority in the Upper House; legislation passed by the Lower House was rejected by the Upper House, bringing the Government to a standstill. In the course of my research, I question this state of affairs: does it benefit the Japanese people? If not, what aspects of which laws should we amend?

Ultimately, a referendum is required to amend the articles of the Constitution. However, when it comes to laws and rules that relate to but do not form part of the Constitution, they can be changed via normal low-making procedures—so long, of course, as these changes are permitted under existing Constitutional Law.

If we can gradually change these laws, and if we can ensure that these changes result in a more accurate reflection of the vox populi, then we should be able to improve the lives of the Japanese people. This is the end-goal of my research, and this is what inspires me to continue my research.

Identifying issues by comparing Japanese laws with those of other countries

If we wish to change our laws and rules, we must draw on the power of politicians, who are the representatives of the people—and, to begin with, we must make these politicians aware of the need for such change. To this end, I publish as many research papers as I can, and have them read by as many politicians as possible.

As I mentioned earlier, my method of research is to compare Japanese laws with laws in the U.K. and in Germany, which offer plenty points of reference in terms of the administrative frameworks of their laws. By comparing Japanese laws with the laws of these countries, we can identify differences and potential issues. When opportunities arise, I try and talk with politicians directly about the content of my research and my proposals.

Put simply, the reason I continue my research is because I like humans and society. The Diet and the Cabinet are organizations that we humans have created; and the activity we call politics takes place in these organizations.

Politics has the power to make our lives better or worse; however, our lives and our human rights are protected by laws. And it is for this reason—to protect our lives and, if at all possible, to make our lives better—that I hope to continue making a difference from my third-party perspective as a researcher of laws, and to continue speaking up and speaking out.

The book I recommend

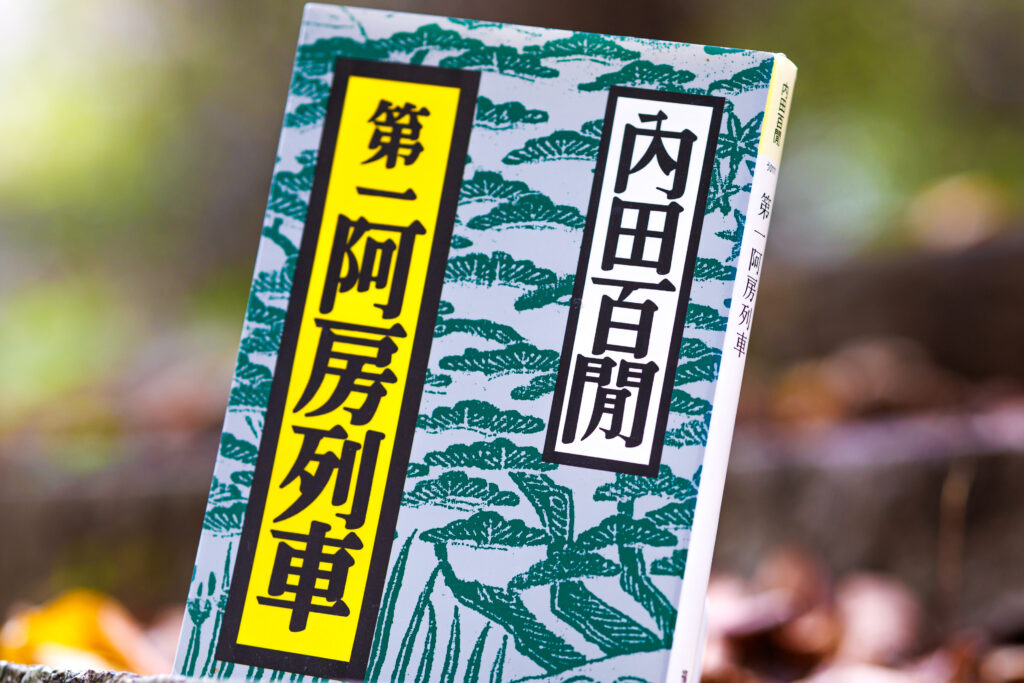

“Daiichi Aho Ressha”(The Aho Train, part one)

by Hyakken Uchida, Fukutake Shoten

Graduated from the Faculty of Law, Kyoto University. Withdrew from the Graduate School of Law, Kyoto University; received a Ph.D. in Law. Worked as a full-time lecturer at Nara Sangyo University (now Nara Gakuen University), as an associate professor at the Kindai University Faculty of Law, and as a professor at the Kindai University Graduate School of Law, before being appointed to his current position in April 2022.

-

Kensuke Ueda

- Professor

Department of Law

Faculty of Law

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Faculty of Law, Kyoto University. Withdrew from the Graduate School of Law, Kyoto University; received a Ph.D. in Law. Worked as a full-time lecturer at Nara Sangyo University (now Nara Gakuen University), as an associate professor at the Kindai University Faculty of Law, and as a professor at the Kindai University Graduate School of Law, before being appointed to his current position in April 2022.

- Department of Law

Interviewed: November 2022