Professor Sven Saaler of the Faculty of Liberal Arts focuses on historical memory in his recent research. He says historical memory serves to convey a certain historical view to the public, so when a society or a political system changes, memorials are demolished and memory is reconstructed. Learning from history is to take lessons from past events, he adds.

In my recent research, I mostly focus on historical memory as expressed in memorials, museums, and monuments, mainly those built in Japan after the late 19th century. Generally, memorial buildings are a modern phenomenon. They convey a certain historical view to the public. When viewing memorials, therefore, we need to be aware of how and why they were created, how they developed, and the role that they played in history, politics, and society.

Destruction of Historical Monuments is a Widespread Phenomenon

The American Revolutionary War began with the overthrow of the statue of King George III of Great Britain in the center of New York. American rebels toppled, destroyed, and melted the statue down because they wanted to show that they did not want to be ruled by a king any more. It stood for less than 10 years.

In the recent past we have witnessed controversial debates about the statues of kings, politicians and soldiers in the US as well as European countries, and some of them were demolished. Such demolitions are common phenomena because when a society or a political system changes, people don’t necessarily want statues that represent the previous society or its values to remain in the public space anymore.

As a historian, I prefer the preservation of such statues in museums with accompanying explanations instead of vandalizing memorials, even if they contrast with the new values of a society.

The recent toppling of controversial statues is the result of the failure of decades-long negotiations and discussions that did not bring a change to the status quo . Some groups argue in favor of the preservation of a statue, while others demand its demolition, and the process to reach a conclusion is often very difficult. If those who want to keep a statue in the public space or have it relocated fail to be persuasive enough, then the statue is often toppled or destroyed. This isn’t a new phenomenon and occurs frequently throughout history.

I think there might be other solutions than demolishing memorials, but in the end, toppling statues often is the solution to the question of how to deal with controversial effigies that are offensive to a large part of the population. Statues of slaveholders are a prime example in this context. Glorifying slaveholders by allowing their statues to remain in public space should not be seen as an option in the twenty-first century—200 years after the illegalization of slavery.

Changing study trajectory from Europe to Japan

Upon entering university, I began my studies at the Department of History. After a few years, I felt the need to look beyond European history which still stands at the center of academic history in most European universities. People recommended Japanese to me because few had knowledge about the language in the 1980s, when it was a difficult time to get a job. Later, I began to study Japanese history, focusing on the modern period. That is because today‘s world is mainly shaped by what happened in the late 19th and the early 20th century.

Basically, the study of history is the process of reading. Historians read and collect as much material as possible and analyze the content in a particular way. It’s important for us to work with evidence and look at what other historians and scientists have written, following the saying, “standing on the shoulders of giants.”

Since there are generations of historians before us, we don’t have to start from zero. We build up new ideas through discovering new evidence and taking into consideration previous research. Sometimes it’s difficult to obtain details that go beyond the written word in books; that lie below the surface. But, in rare cases, we can come into contact with the personal emotions or insights of people who failed in making major decisions by reading their diaries or letters.

There is a famous episode about the French Revolution. The revolution started with the storming of the Bastille. But the French King wrote in his diary, “Nothing special today.” He knew nothing about the developments taking place outside, or simply was not interested in rioting commoners. Learning from history is to take lessons from certain injustices in the past in order to do better in the future. Certain politicians active today could definitely learn a lot from history, but they never cease to disappoint historians in their failure to do so. It is frightening to see that this has led to the real possibility of another World War.

The book I recommend

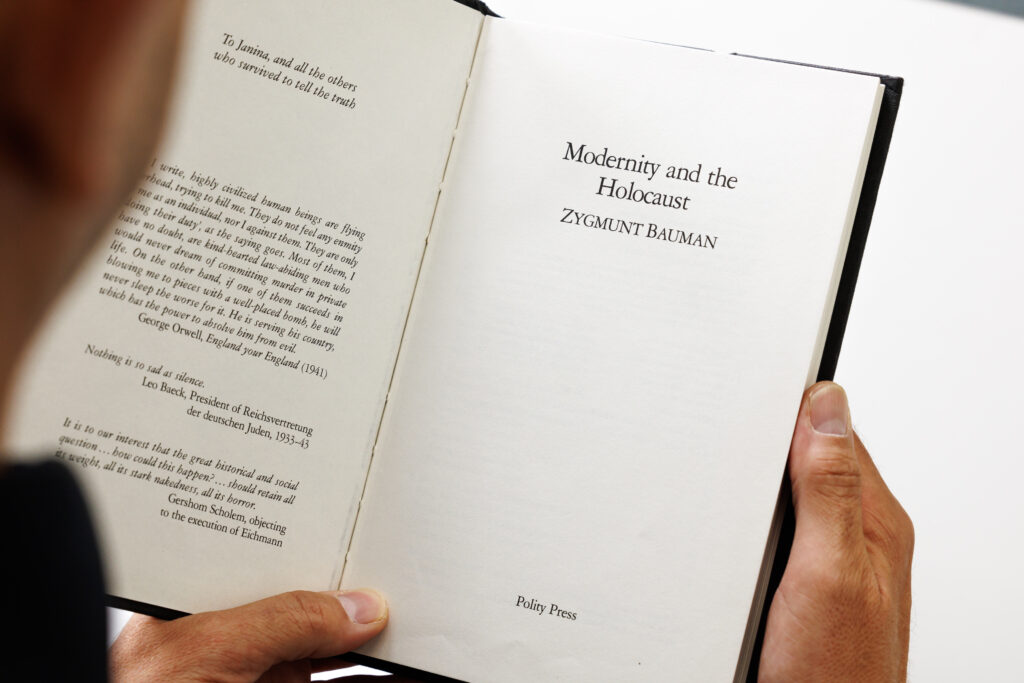

“Modernity and Holocaust”

by Zygmunt Bauman, Polity Press

The Polish author Zygmunt Bauman emphasizes that the Holocaust was a product of modernity. Such an event could be caused again if the conditions—racism, modern technology, and the idea of bureaucratic efficiency—come together. Overemphasis on the uniqueness of the Holocaust may blind us to this possibility. I think we need to nurture critical views of the ingredients that allowed the Holocaust among our students.

-

Sven Saaler

- Professor

Department of Liberal Arts

Faculty of Liberal Arts

- Professor

-

Sven Saaler earned his Ph.D. in Japanese Studies and History from Bonn University. Afterward, he was a lecturer at Marburg University (1999-2000) and Head of the Humanities Section of the German Institute for Japanese Studies (DIJ) in Tokyo (2000-2004), and he also taught at The University of Tokyo for four years. He is an editor of The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus and a member of the Advisory Board of the National Institutes for the Humanities (NIHU). He is also author/co-author of more than twenty books and almost 100 articles about modern Japanese history and politics. He joined Sophia University in 2008.

- Department of Liberal Arts

Interviewed: August 2022