Professor Chie Kasahara of the Faculty of Human Sciences studies welfare for the disabled with a focus on “participation” and “cooperation.” Here, she talks about persons with intellectual disabilities not as the subjects of researchers and their investigations, but as partners in “inclusive research.”

“Inclusive research” is an approach that seeks to transform the power dynamic between researcher and researchee: typically, the researcher carries out research on the researchee; but in inclusive research, persons with intellectual disabilities actively participate in the research process—from initial plans to execution—such that the researcher carries out research with co-researchers.

Of course the results of the research remain important. However, inclusive research is characterized by its emphasis on feeding back both the research findings as well as the realizations gained by the researcher and co-researchers through the research process, with the goal of realizing an inclusive society.

While there is a great deal of investigative research into persons with intellectual disabilities, the majority of this research positions the persons with intellectual disabilities as the object of observation or experimentation—answers are supplied by their guardians or care-givers.

As a postgrad student, I felt a sense of unease about such methods, and so I was deeply impressed when I encountered inclusive research. Due to the influence of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the results of research in the field of disability studies, overseas inclusive research is now being used in various areas.

However, it is not just a matter of making inclusive research more widespread—we must question who the research is being carried out for, and ask whether the co-researchers are actually participating, or participating in name only.

From the perspective of persons with disability

In my current research, I am evaluating the quality of life in local communities from the perspective of persons with intellectual disabilities, and encouraging local governments to incorporate my findings into the formulation process of their welfare plans.

By examining the extent to which persons with intellectual disabilities are included in or excluded from society, I hope to identify issues with local communities and welfare services that prevent such persons from fully participating in community life; and I hope to develop methods for these communities and services to work directly with persons with intellectual disabilities.

Social exclusion is a concept that seeks to explain the diverse forms of poverty that exist today—forms of poverty that cannot be quantified through economic yardsticks alone.

Social exclusion seeks to dynamically understand the relationships of all persons, their methods for participating in society, their capacity for such participation, and how communities can best empower them to participate.

Governmental policies for social inclusion tend to be geared toward helping all persons achieve independence, and specify employment as the ultimate goal—but such “inclusion” policies can, in fact, result in new forms of exclusion.

In our meritocratic societies, persons with intellectual disabilities are easily excluded—how do they experience life in local communities? how do they interact with society? There are many questions we do not yet have answers for.

Community welfare, which is becoming a mainstream form of social welfare in Japan, encourages the participation and cooperation of all citizens, regardless of whether they use social services or not. But such an approach only attends to the voices of persons who are capable of participating—it does not incorporate the voices of those incapable of participating, and so it does not reflect the full diversity of the local population.

Research carried out with and by persons with intellectual disabilities

If we can break free from conventional approaches, then there are many ways in which the thoughts and opinions of persons with intellectual disabilities can be expressed.

For example, “photovoice” uses photos taken by persons with intellectual disabilities as the basis for conversation; in “mobile interviews,” persons with intellectual disabilities participate in interviews while showing researchers around their local communities.

Such methods reveal how persons with intellectual disabilities interact with their communities, and what factors influence them and their relationships with the community.

In addition, discussions based around “dot-voting” surveys have shown us that existing plans for disability welfare are lacking in some respects when it comes to providing support for persons with intellectual disabilities.

Through such research, I have come to realize that persons with intellectual disabilities are not prevented from expressing their opinions because of their disabilities—rather, they have been deprived of the opportunity to learn, to converse with other people, and to say what they feel.

If we wish to become fully inclusive as a society, simply improving our social welfare systems is not enough—we ourselves must change. Going forward, I hope to engage in research with persons with intellectual disabilities—using topics they have selected—to identify the factors that make their lives hard to live.

The book I recommend

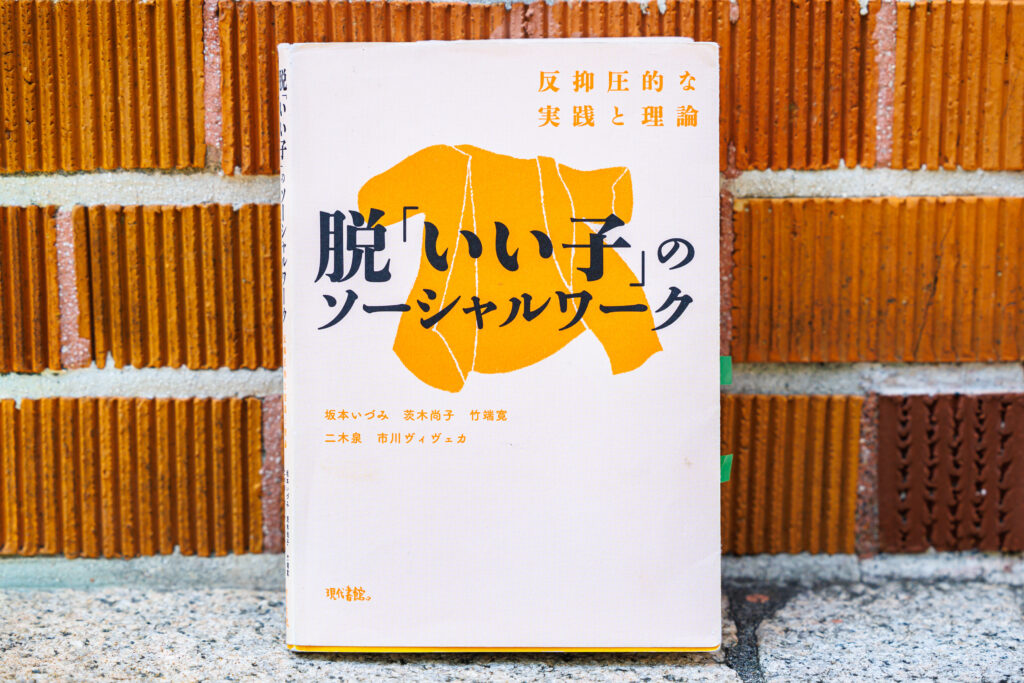

“Datsu ‘iiko’ no sosharu waku”(Beyond being a ‘good’ social worker)

by Izumi Sakamoto, Naoko Ibaraki, Hiroshi Takebata, Izumi Niki, and Viveka Ichikawa, Gendai Shokan

This book is about “anti-oppressive practice,” an approach premised on the idea that power imbalances in organizational structure are the root cause of exclusion. It explains why studying and practicing social welfare has tended to be considered an act of kindness; it shows how readers can work together with persons with intellectual disabilities to devise and put into practice ways to structure society.

-

Chie Kasahara

- Professor

Department of Social Services

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Professor

-

Professor Chie Kasahara graduated from the Department of Social Services, Faculty of Humanities, Sophia University; she worked as a social worker at a rehabilitation facility for persons with intellectual disabilities, before receiving her Ph.D. in Social Welfare from the Graduate School of Humanities, Sophia University. Kasahara worked as a lecturer at the School of Human Studies, Kansai University of International Studies, then as an associate professor at the university’s School of Education, before being appointed to her current position in 2018.

- Department of Social Services

Interviewed: August 2022