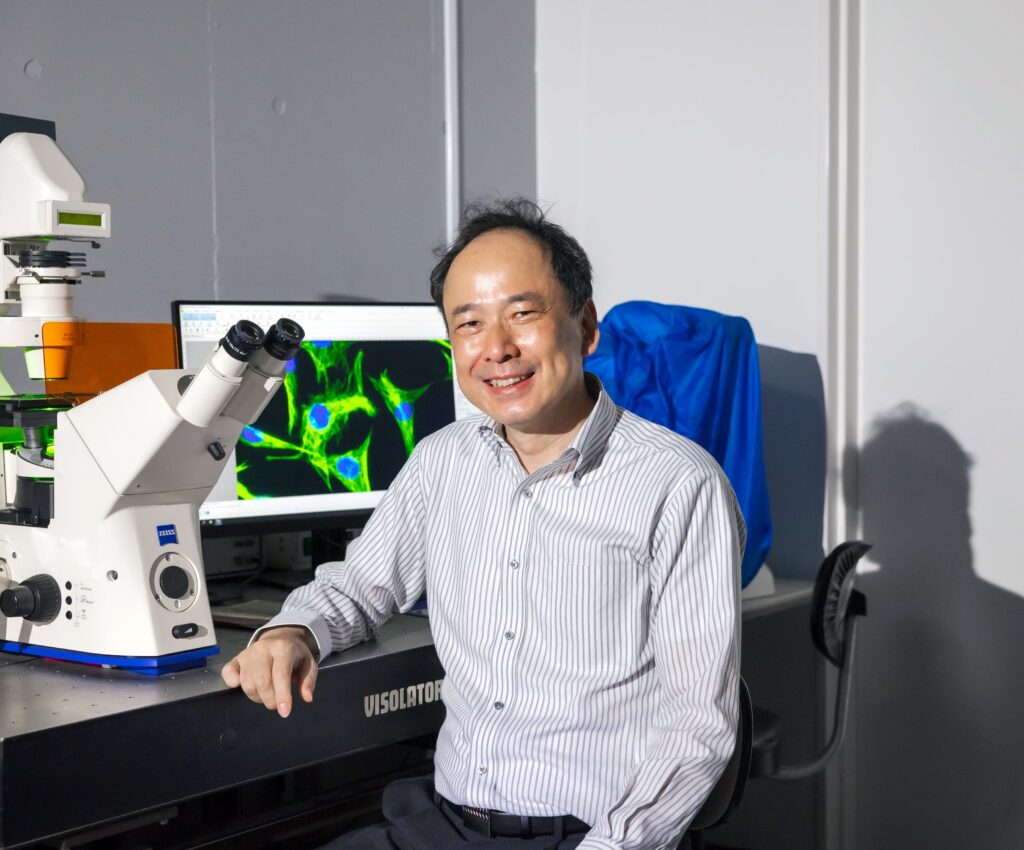

Professor Hayashi of the Faculty of Science and Technology researches the mechanism by which dendrites grow. Dendrites are one of the projections extending out from neurons in the brain and serve as antennae. He talks about how he learned about the generation of the microtubules that form the framework for these dendrites, and the possibilities of his research for health and medical treatment.

All animal activity, from senses to memory, from thoughts to movement, are governed by the brain. These functions are carried out by the roughly 100 billion neurons in the brain, which receive and transmit information to and from each other. My research explains the mechanisms behind the generation of these neurons. Currently, I am focusing on dendrites, which serve as antennae that receive information, and am looking into the microtubules that serve as the framework for these dendrites.

Dendrites send out projections, rather like the branches of a tree, to make contact points with multiple neurons around them. This point of connection between two neurons is called a synapse. Several thousand to several tens of thousand synapses form on the surface of a dendrite, passing on information between neurons. In other words, the surface area of a dendrite affects the number of synapses, and thus the functions of the brain. To maintain the health of the brain, it is important that dendrites remain properly extended, so they can send information all over the brain.

However, dendrites shrink with age, reducing the number of synapses. This is one of the causes of the brain aging. Several diseases can also cause dendrites to atrophy. During brain development, a large number of fibers called microtubules, which serve as the framework supporting dendrites from the inside, need to be created, and created continuously, to ensure that the dendrites are able to grow long and maintain their shape indefinitely. By learning the workings of the mechanism by which these microtubules are created, we might be able to prevent the brain aging or treat illnesses.

The special mechanism of dendrites, antennae of the neurons.

We use mouse embryos in our experiments to learn how dendrites grow. We culture neurons obtained from embryo brains, and inject genes to encourage or control microtubule growth, and observe the dendrite microtubules through laser microscopes.

Recently, we have learned that the mechanisms by which microtubules form are different between neurons and other organ cells. Cells in other organs have microtubules that extend radially from the center of the cell. However, neurons have microtubules that extend from all over the cell, in random directions. We think this is a unique mechanism of neurons to allow dendrite branches to extend freely when the microtubules cause dendrites to grow.

Conversing with our ancestors through the lens of a microscope.

The appeal of neurons is that we can physically see their shapes and movements through the microscopes. Life began as single-celled organisms some 3.8 billion years ago, and the life phenomena that started back then still exist in the cells we look at today. When I peer through a telescope, it feels like the cells I see are my own ancestors; like I am having a dialogue with my ancestors. At the same time, as I carefully observe cells, I might see molecules I did not expect, or realize that their distribution is different. New mysteries continue to appear, giving me ideas for new research.

For future research, I would like to investigate how the mechanism for the unique microtubules on neurons is adjusted. If we know what the adjustment mechanism is, then we can apply it to developing medication to prevent dendrite shrinkage. I would love it if my research could help people be healthier and happier.

The book I recommend

“The Naked Ape: A Zoologist’s Study of the Human Animal”

by Desmond Morris; translated into Japanese by Toshitaka Hidaka, published by Kawade Shobo Shinsha

The author, an animal behavioral scientist, observed and analyzed human behavior from the perspective that humans are “naked apes.” I encountered this book at university, and it got me interested in understanding the knowledge and awareness that human brains create.

-

Kensuke Hayashi

- Professor

Department of Materials and Life Sciences

Faculty of Science and Technology

- Professor

-

After receiving his B.Sc. and D.Sc. from the School of Science, University of Tokyo, he worked at the National Institute of Neuroscience, Gunma University School of Medicine, Gunma University Institute for Molecular and Cellular Regulation and others, before taking up his current post in 2004.

- Department of Materials and Life Sciences

Interviewed: June 2022