Professor Akira Sakai of the Faculty of Human Sciences is a specialist in the sociology of education. He researches education with “clinical” as a key word. He terms his own research “clinical sociology of schools,” and places importance on visiting schools and various other educational institutions, where he talks directly with the people involved and considers measures together.

I am reevaluating accepted norms in education, something that we take for granted, digging up issues that have been overlooked, and considering what responses are needed. My focal point for these issues is the key word “clinical.” This is because I believe that the clinical perspective of lending your ear to the suffering and worries of each and every person with problems, is useful for understanding what is going on with how education is carried out and what is happening with the children. From this desire, I termed my research field “clinical sociology of schools,” and apply it to both research and also teaching.

One of the themes I am currently looking at is how we can ensure learning for all children, now that we are seeing more children refusing to go to school. This refusal tends to be seen as a mental health issue, and has usually been treated through psychological counseling. However, a more careful examination shows that there are, in addition to psychological factors, social and economic factors interacting in a complex fashion.

Shining a spotlight on the hidden issues of chronic absenteeism

Recent years have seen increased social focus on “young carers.” There are believed to be a certain number of children who, having to take care of their parents or grandparents, have their daily rhythm disrupted and so tend to not go to school. If we only consider chronic absenteeism a mental health issue, we will be unable to see the sort of problems faced by these children, and we will overlook the many children who do not go to school for other reasons. In that sense, I believe we need to look at the whole picture for children absent for the long term.

While chronically absent pupils are increasing yearly, correspondence schools are being examined as a way for them to move on after middle school. In the 2021 academic year, there were 218,000 pupils in correspondence schools, the highest number ever. While it is good to offer diverse learning opportunities, with online interaction, it is harder to see what sort of lives the children are leading at home or in their community, and so the problem becomes harder to grasp.

In addition, children with foreign nationality in Japan are not required to attend compulsory education, and what is going on with them is extremely unclear. The Ministry of Education conducted its first nationwide survey of these children in 2019. In the 2021 survey, concerns were raised that more than 10,000 children with foreign nationality were not attending school. This sort of issue is another of the major problems behind non-attendance.

Learning about the people involved through qualitative research

My main research method involves interviews with people connected with schools, supporters, parents or guardians, and the children facing issues themselves, along with visits to schools or support sites to observe and record. This is generally termed “qualitative research.” Due to wanting to get close with each person involved, I focus on methods to understand their way of thinking and values. For the last two years, it’s been difficult to talk face-to-face due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but as the infections seem to have stopped spreading as much, I have been gradually getting back to this method. My policy is to do my research as close to the field as I can.

As we need to continue learning even in the COVID-19 pandemic, the distribution of tablet devices for each person and the development of high-speed, high-capacity communication networks made notable advances. This means that it is now technically possible to get an education even if you don’t go to school. We used to think that you had to go to school to get an education, but now this system of education itself is being reexamined. We need to think more about what sort of education is the most desirable for children in the future.

The book I recommend

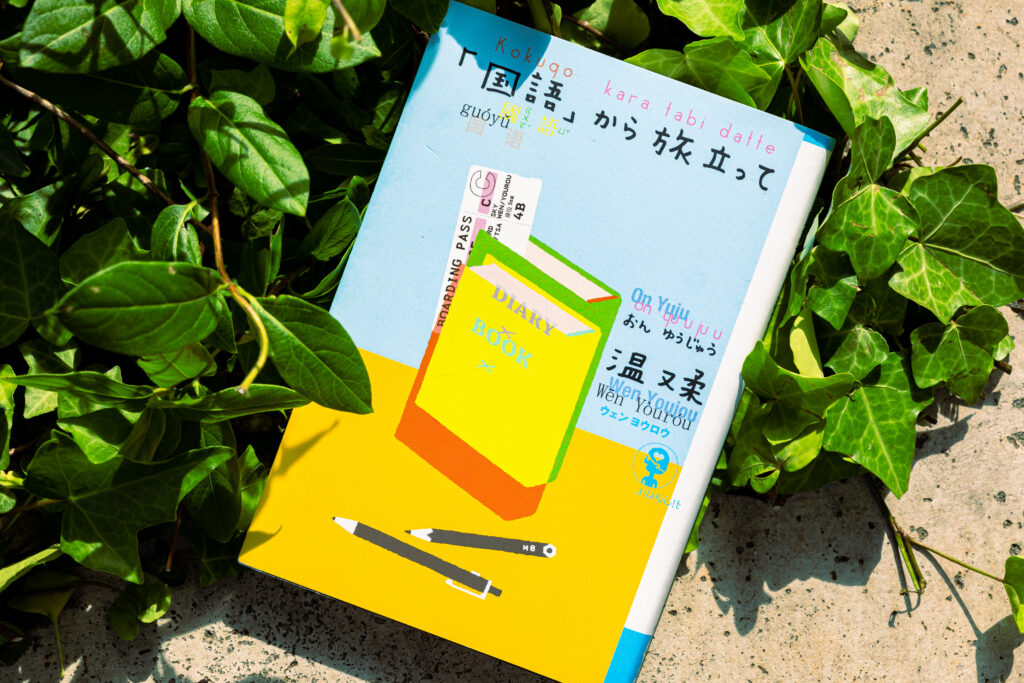

“‘Kokugo’ kara Tabidatte”(A Journey from ‘National Language’)

by Wen Yourou, Shinyosha Publishing

The author was born in Taiwan, but moved to Japan when she was two. The book beautifully describes growing up without really knowing what your own language is, caught between Japanese, Chinese, and Taiwanese. From understanding the conflicts among children in different circumstances and their experiences of school, this book offers a number of suggestions.

-

Akira Sakai

- Professor

Department of Education

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Professor

-

Born in 1961. After completing the doctoral course at the University of Tokyo, he worked as lecturer, associate professor, then professor at Nanzan University and Ochanomizu University, then was appointed to his current post after working at Otsuma Women’s University. His research fields are the sociology of education and the clinical sociology of schools.

- Department of Education

Interviewed: May 2022