Professor Kyoko Yokoyama of the Faculty of Human Sciences specializes in pediatric psychology, a branch of clinical psychology. She researches mental health support for children suffering from pediatric cancer or chronic illness, and their families. Building on her knowledge and experience of psychology, she provides support considering the children’s future.

Clinical psychology is the study of treating and supporting people with mental health problems and seeking practical solutions. Within this field, I specialize in pediatric psychology, which provides support for sick children and their families.

Children suffering from illnesses such as pediatric cancer, inherited immune disorders, heart disease, epilepsy or type 1 diabetes have many different problems and worries. For example, with pediatric cancer, rapid advances in medicine have enabled children who previously would have had no hope to survive. At the same time, there are more children suffering from the effects of chemotherapy, radiation therapy or surgery. Their growth is stunted, their hair thins, they suffer learning disabilities and other symptoms, or even lose part of their body. They all suffer in their own way. Many children who have been hospitalized from a young age feel fear of other children or an inability to understand them, and are unable to attend school.

My research theme is on supporting these children, and their families, using knowledge and experience of psychology and clinical psychology.

To offer peace and hope for tomorrow, even if the illness is incurable

I do most of my research in pediatric wards and outpatient services in hospitals. Talking one-to-one with children, I use clinical psychology tools such as art therapy or play therapy to understand their world and mental state.

The words, facial expressions, actions and so on during this play let me peek inside the child’s mind. I want them to express whatever they are feeling – if worried, then express worry. Even if we can’t get rid of that feeling, we might be able to share the worry together. The minor reassurance of having someone understand you will, I hope, become the strength to enjoy tomorrow, the power to confront fear.

Play is very important for children. Even for diseases for which we have no cure, people do not live through despair alone. Even for diseases where the prospects of living just another year, let alone a decade, are difficult, finding something enjoyable might allow the patients to find hope.

On the day before a certain child had died, they had said: “I can’t wait to see what fun things me and Professor Yokoyama will do tomorrow!” I am learning from the children, such as this child, that it is possible to keep feeling hope for the future, even at the brink of death.

For a future where having a psychologist in the medical team is standard

With advances in medicine, it’s no longer solely a question of “can it be cured?” Mental health support for people suffering from physical ailments is only going to get more important. In Japan, there are not many psychologists in this field yet, but gradually more and more certified public psychologists or clinical psychologists are being added to medical teams, and in some cases, the psychological treatment for patients suffering from physical ailments can be covered by insurance.

The US is in the lead here. The field of medical psychology is advanced there, and offers a lot of pointers. But we must remember not to decide that since such-and-such literature exists, then this child will be the same, and directly confront the feelings and thoughts of each patient.

The human soul is complex. At times, cruel. At other times, capable of astonishing recovery. A lot of attention is paid to growth and changes in children in particular. I personally love hands-on clinical work, but my future goal is to create theories based on my experiences there, and spread them widely.

The book I recommend

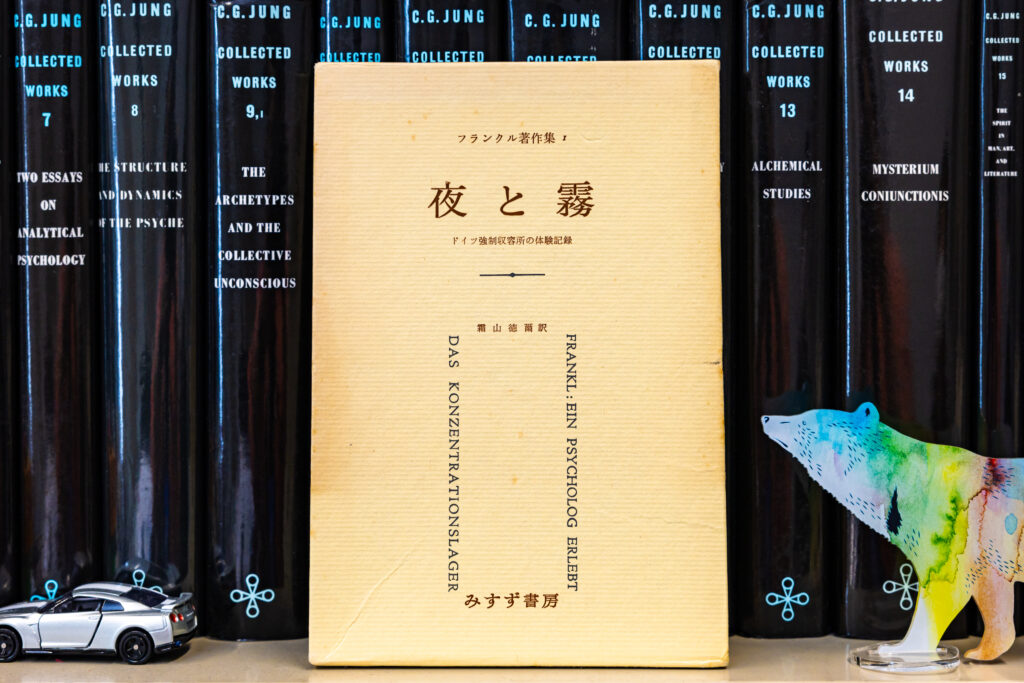

“Ein Psychologe erlebt das Konzentrationslager”(Man’s Search for Meaning)

by Viktor E. Frankl, Japanese translation by Tokuji Shimoyama, Misuzu Shobo

This was translated by my professor when I was an undergraduate and graduate, and describes human hope and despair under the extreme circumstances of a concentration camp. For me, as my grandfather had told me of his wartime experiences, I remember thinking not just from the victim’s point of view, but that I might actually be one of the oppressors.

-

Kyoko Yokoyama

- Professor

Department of Psychology

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Sciences at Sophia University, received her master’s degree in Education from the university’s Graduate School of Human Sciences, and withdrew from the doctoral program after completing the course. Worked as assistant professor in the Department of Human Sciences, Faculty of Humanities, Toyo Eiwa Women’s University, associate professor in the Department of Human Sciences, Faculty of Human Sciences, and associate professor in the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Human Sciences at Sophia University before being appointed to her current post.

- Department of Psychology

Interviewed: May 2022