People think using words. Writing these on paper allows thoughts to be shared with many people, transcending time and space. As communication methods move from paper to digital, will it affect the way we think? Professor Shigeo Kawaguchi from the Faculty of Humanities approaches this question from the perspective of philosophy.

Language and thoughts are not equal, but people cannot think without language. At the same time, thinking is bound by language. The academic field that studies language and thinking is called “linguistic turn” philosophy, also known as the philosophy of narratology.

When we are faced with a situation, we look for meaning and reason. For example, when thinking, “This room is hot,” we could provide reasons in units of several hours by saying “It’s sunny today,” or in terms of centuries by noting “It’s hot in autumn due to global warming.” This is because we think of causes, results, and processes using various scales.

We might also think, “It would have been good if people in the 19th century noticed environmental issues.” Expressions stating the unrealistic past, equivalent to the subjunctive mood in English, exist in many languages. Developing stories about other possibilities is another human characteristic.

Philosophy ascertains how thinking changes during the turning points of the times

Human language is closely linked to paper. Particularly in the past 500 years, it can be said that human thinking was given shape by paper and ink. However, about 20 years ago, human language started to be transported by Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) and radio waves. It is also the job of philosophy to ascertain the things that change and do not change in human thinking during major turning points of the times.

I am focusing on the issue of the speed of language. Changing from paper to LCD, the flow of words has become faster. Although it takes time to produce paper books, they can be made with care and remain as they are once completed. Meanwhile, information shown on LCDs is fast but often not polished, and may also be changed, modified, or deleted instantaneously.

Social issues, understanding of history, and other things that should be fully explained using words are shown on the screens of smartphones quickly with a short sentence that “This is true.” People on the receiving end worry whether they are approaching the correct opinions.

It is also an issue that, in an attempt to quickly alleviate worries, people tend to see things in simple, dichotomous frameworks. It becomes difficult to see other possibilities and other scales. Having several opinions when there are several people was supposed to be enriching.

Taking in words after thinking about the nourishment they provide

Going further, this is possibly the first time in history where we have such an abundance of poorly written language. Poor-quality language has always existed, but was often spoken and transient. However, I do not believe we should force so-called “good” language onto other people, nor is it constructive to simply criticize or look down on people who use poor language.

I believe we are in an era where instead of mindlessly taking in any words that reach us, we can make a conscious decision in choosing words, by considering how they can enrich us. It gives us the freedom to consider what type of nourishment we need for thinking, or what kind of words we want to tune in to. It requires more effort, but is far better than an era where we are forced to digest words prescribed as the only correct choice.

Philosophy often comes across as abstract, but it is an academic field that has responded practically to the issues of society since old. Today, we can think about the speed of language immediately after becoming a digital society because, for over 100 years, many philosophers have continued to ponder the question “What is time?”.

It is also the role of philosophy to check and interpret the words written by past philosophers against modern issues and carry out fresh maintenance on human thinking over the medium-to-long term.

The book I recommend

“Sein und Zeit (Being and Time) Vol. 1”

by Martin Heidegger, Japanese translation by Tasuku Hara and Jiro Watanabe, Chuokoron-Shinsha

Specializing in French philosophy at university, I often came across critiques of German philosopher Martin Heidegger. Yet, when I read his work, I was struck by his tough and attractive thinking—and later found myself imitating him in speech and thought. A reminder of the challenge of engaging deeply while maintaining distanced objectivity, it’s a book worth reading again and again.

-

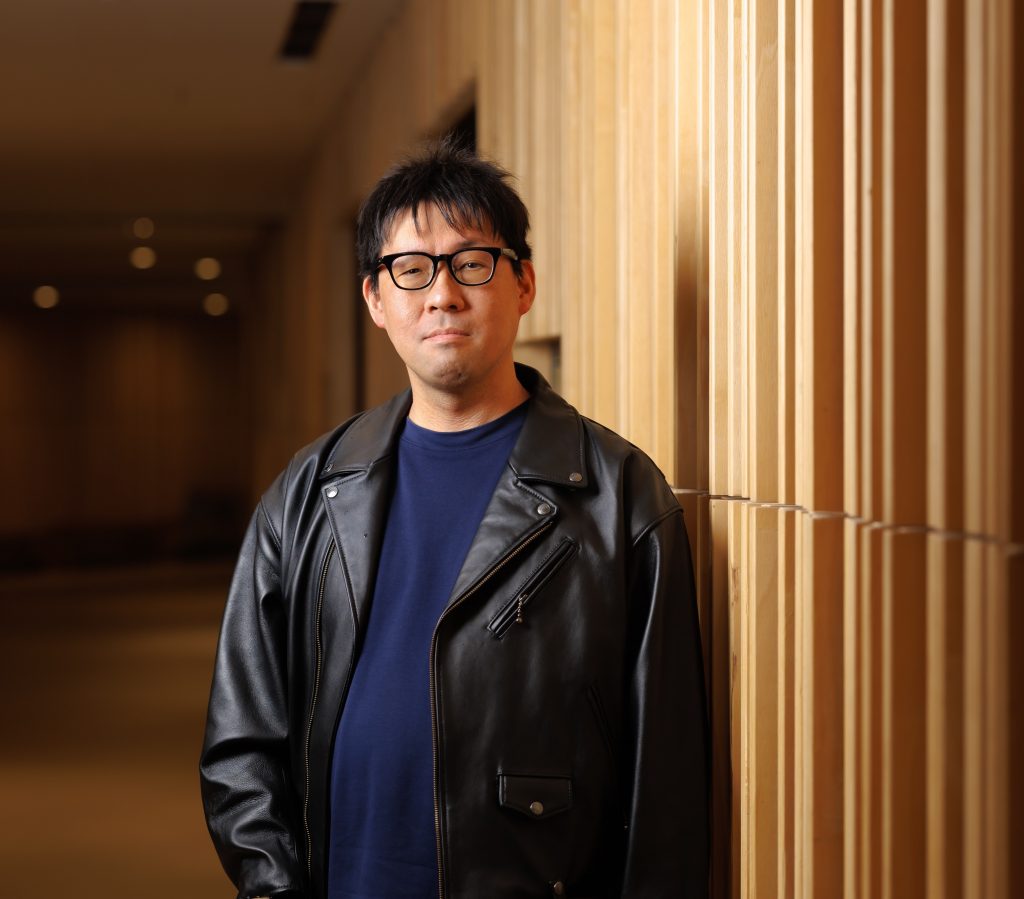

Shigeo Kawaguchi

- Professor

Department of Philosophy

Faculty of Humanities

- Professor

-

Graduated from the Faculty of Letters, Kyoto University and obtained his Ph.D. in Literature after completing the doctoral program, with research guidance approval, at the university’s Graduate School of Letters. Took on several positions—such as research fellow (PD) of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (at University of Tokyo), associate professor at the Faculty of Letters, Konan University, visiting scholar at Technische Universität Berlin, and associate professor at the Faculty of Humanities, Sophia University—before assuming his current position in 2024.

- Department of Philosophy

Interviewed: October 2024