Associate professor Itsuki Nagasawa from the Center for Language Education and Research unravels the history of the Japanese language using practical documents such as judicial records. She talks about the image of people from long ago formed by these documents and the uniqueness of the Japanese language.

When talking about research that explores the history of the Japanese language, people may imagine literary works of Heian-period aristocrats or grammar used in classical works, but these are just a small part of the diverse documents written in Japanese. There is still a mountain of materials yet to be researched by anyone. Among these materials, I utilize court judgments and other documents with deep ties to daily life, in my research on the history of the Japanese language and its use of words.

The determination of judges to find a way to be understood

Among the materials I have researched so far, court judgments from the 1930s written in colloquial Japanese left a deep impression on me. In Japan, language has been divided into the written literary style and the spoken colloquial style ever since the Heian period. Entering the Meiji era, the Genbun Itchi movement arose to align the written language with the spoken one. Newspapers, novels, and such started to be written using colloquial Japanese.

However, court judgments and other official documents continued to use the traditional literary style. It was only in the 1930s that revolutionary judges started to write court judgments in colloquial Japanese in full force.

When you read these court judgments, you can see that the judges were trying to find the right style to record their decision. For example, the sentence “The court cannot believe (omitted)” uses the court as the subject, indicative of the colloquial style. However, it was not that straightforward as at the same time, judicial decisions were written in a dignified manner in literary Japanese, and there were discussions on the appropriate colloquial forms for ending sentences.

Looking through other materials revealed the background behind why judges of that time tried to write court judgments in colloquial Japanese. There was a strong belief that using words that can be understood by any member of the public would help to uphold the dignity of the court in the true sense.

We also came to understand that judges also felt it difficult to convey logically in the old literary style, and they hoped to improve the quality of court judgments by using colloquial Japanese. From these old documents, I felt the passion of people from those times and was moved by them.

Also focusing on modern issues such as being able to speak but not write

Recently, I have been investigating with interest Goseibai Shikimoku—the legal code of the samurai during the Kamakura period—and judicial documents called “saikyojo.” They are written in a Japanized Chinese style that is different from the kanbun (Chinese writing) of China.

They are kanbun but use grammar and vocabulary unique to Japan, and serve as valuable materials when tracing the history of written Japanese. At the same time, it is fascinating as they vividly convey the way words change when the different languages of Chinese and Japanese come into contact.

Modern Japanese is a rare language in the world because it uses four types of characters at the same time: kanji, hiragana, katakana, and the English alphabet. While this is also the charm of the Japanese language, it become very hard to understand when written.

The students of the Japanese classes that I conduct at the university are people who have lived (and studied) overseas as well as those who have attended international schools. They have extremely strong language skills, having been brought up in environments that use several languages.

However, they struggle to learn written Japanese and kanji. When teaching them, research related to colloquial and written Japanese as well as research about the changes that occur when different languages come into contact often become useful. Going forward, another theme is to take the knowledge obtained from research into the history of the Japanese language and apply it to research on pedagogy for teaching Japanese.

The book I recommend

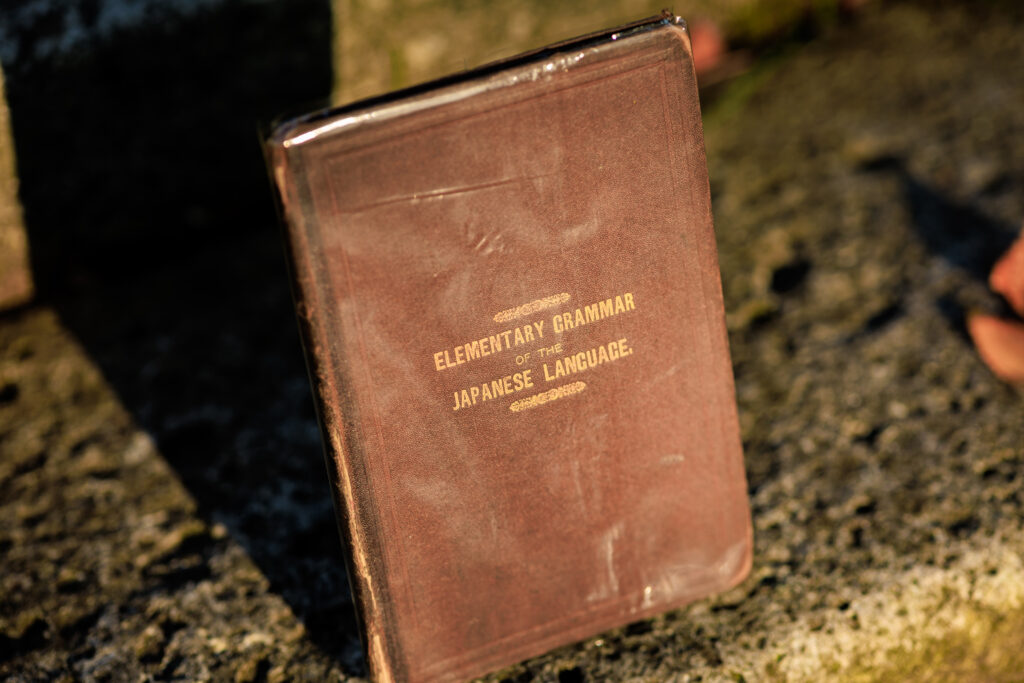

“An Elementary Grammar of the Japanese Language: With Easy Progressive Exercises”

by Tatui Baba, Trübner

The author opposed an early Meiji-era opinion about substituting the Japanese language with English, writing this book to show that Japanese is just as good as foreign languages as a way of thinking and means of expression. Written 150 years ago, it is fascinating for its views on grammar—which remain relevant even in modern times—and the coexistence of surprisingly different views on grammar.

-

Itsuki Nagasawa

- Associate Professor

Center for Language Education and Research

Graduate School of Languages and Linguistics

- Associate Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of Linguistics, Faculty of Letters, the University of Tokyo, and received her Ph.D. in Linguistics after completing the doctoral program in Linguistics at the university’s Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology. Took on several appointments—such as assistant professor at the University of Tokyo and associate professor at Nagoya University—before assuming her current position in 2022. Has worked concurrently as an associate professor of the Graduate School of Languages and Linguistics at Sophia University.

- Center for Language Education and Research

Interviewed: October 2023