Associate Professor Yuko Okawa from the Faculty of Humanities undertakes research on the history of pre-modern China, in particular, its history regarding the environment. She conducts fieldwork while deciphering historical materials to study how people have lived together with nature.

I used to conduct research on the Qin and Han dynasties which existed 2,000 years ago, but reading “Shiji,” or “Records of the Grand Historian” by Sima Qian, sparked my interest in the state of Qin. Starting as a small state, Qin was the first state to unite China. “Shiji” stated that Qin was able to achieve this feat because it used the natural environment to strengthen its national power.

A famous example is Dujiangyan, an irrigation and flood control system in Sichuan Province that has become a World Heritage site. It uses levees to adjust the flow of the Minjiang River, which floods easily, dividing it into a main stream and smaller streams that flow into the Chengdu Plains and turning the area into a major grain production zone.

By the way, the family of Zhuo from Zhao, a state destroyed by Qin, was a clan that accumulated enormous wealth through iron production. It is recorded in “Shiji” that they crossed the mountains and moved to Sichuan—which is rich in nature—with their technology due to Qin’s policy of relocation. Qin grew in size by stabilizing agriculture and relocating the people of states it conquered.

Visiting sites to confirm the natural environment while studying historical materials

It is also recorded in “Shiji” that taro is seen as an important source of food in Sichuan. Although the building of a magnificent irrigation system is emphasized, it is but a small part this history. It is also unique in that it records the diverse lifestyles and cultures of people living in different environments.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I included fieldwork as part of classes to study the lifestyles of commoners. These lifestyles—recorded in historical materials—can be seen in three dimensions by actually visiting those places and experiencing the mountain and river scenery first hand. While today’s scenery may be different, there are things that can be felt by actually going there.

For example, when wind is recorded in historical materials, one can feel the strong winds by being at those places. You can see that the local agriculture and lifestyles were significantly affected by winds.

In this way, fieldwork is good because we can discover various things that you cannot find in historical materials alone. Given that we are unable to travel freely now, unlike before the pandemic, I am considering what to do with fieldwork. However, I hope to recommence fieldwork to let students see and feel for themselves the local environments, cultures, and lifestyles of commoners.

Understanding the values of ancient people is useful to the lifestyles of modern people

As the study of history is first and foremost founded on research based on historical materials, if it is really impossible to visit places, we can continue research based on those materials. Changes in nature and society are in the background of historical materials and reflected in them. What is written is important, but it is also crucial to think about why it was written and the kind of background behind these materials.

I am often asked how the study of history is helpful to society. The study of history does not immediately result in something useful, but one example is that research on past agricultural techniques that carefully observed nature can be applied to modern agricultural measures.

In addition, I also believe that rediscovering the concepts and methods used by people back then to face issues—such as climate change and natural disasters—will be useful to the lifestyles of modern people.

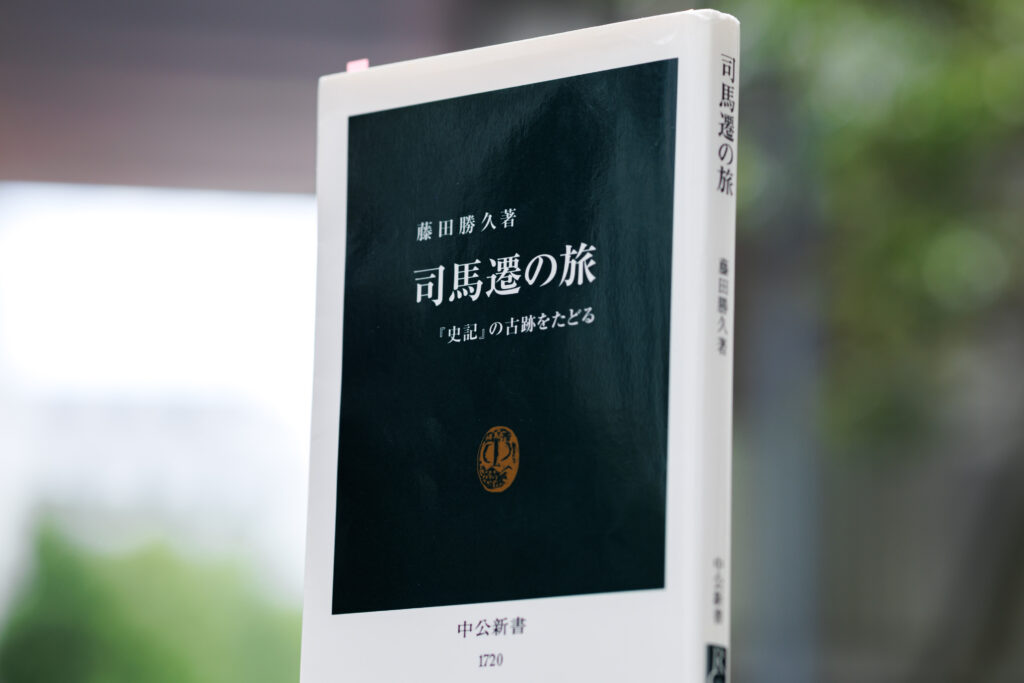

The book I recommend

“Shiba Sen no Tabi—Shiki no Koseki wo Tadoru”(Journey of Sima Qian—to follow the historic site of “Shiji”)

by Katsuhisa Fujita, Chuokoron-Shinsha

Through carefully reading historical records and fieldwork, the author showed that “Shiji” is a record of history and overturned the common view that it is a record of personal experiences. In the study of history, it is important to learn from historical materials based on historical records rather than novels.

-

Yuko Okawa

- Associate Professor

Department of History

Faculty of Humanities

- Associate Professor

-

Graduated from the Department of History, Faculty of Humanities, Japan Women’s University, and received her Ph.D in Humanities after completing the doctoral program in History at the university’s Graduate School of Humanities. Took on various positions—such as research fellow at Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, academic researcher at Japan Women’s University, and part-time lecturer at Sophia University—before assuming her current position in 2020.

- Department of History

Interviewed: September 2022