Dada was a 20th century art movement that opened up new artistic horizons by rejecting the established value systems of institutionalized art. Professor Yuri Komatsubara of the Faculty of Humanities explores the significance of examining Dada within the context of ongoing war.

In the early 20th century, several avant-garde movements simultaneously emerged in Western Europe. One of these movements was Dada, or Dadaism, which is the focus of my research. It was my visit to the “20th Century Exhibition,” organized in collaboration between three major museums in Berlin, Germany, while in graduate school, that sparked my interest in this art movement. Beyond an extensive display of traditional European art was an exhibition room dedicated to Dadaism. In this room, I was shaken by the energy of the Dadaists, who scrupulously destroyed traditional aesthetic norms in search of free, new expression.

Dada was born from anger towards war. At the time, European powers were fighting colonial wars, struggling for supremacy and pushing society towards the First World War. It was in a cabaret in Zurich, Switzerland, where a group of young artists united by the idea of solidarity, as opposed to war, raised their voices to exclaim: “Dada!” The word was apparently picked at random from a dictionary and did not derive from a specific country.

This word reflects the heart of the art movement, to pursue peace through the use of a word free from meaning – a sound, an echo and rhythm, a guiding principle towards a transcendence that goes beyond the barriers of national borders and the divisions between genres of expression, gender, and artists and receivers.

Women artists at the forefront of Dada

Dada is characterized by its attempts to reject the Christian worldview and rationality of European society and to stir up the established order. The movement originated in literature and spread from Europe to the United States, Japan, and other parts of the world as it expanded to other genres of expression, including fine art and physical performance. This pursuit of new artistic expression influenced younger generations, and it is not an exaggeration to state that many of the avant-garde expressions we see today owe their inspirations to Dada.

I am currently exploring the concept of Dadaist transcendence from a gender perspective. There were many women artists at the forefront of Dada. Take Emmy Hennings, for example, who was the co-founder of the cabaret that gave birth to the movement’s name. Though she is known as a cabaret singer, she was in fact an avant-garde performer and writer of substantial works such as Prison, which recounts her own experiences while incarcerated, and Stigma, a memoir examining society from the perspective of a prostitute.

There was also Hannah Höch, a significant Dada artist and originator of the photomontage technique, who explored feminism, gender, and what we would today refer to as queer expression. It is noteworthy that these women artists produced a diverse array of works that explored extremely progressive themes amid the patriarchy of Western Europe around 1920. One of my jobs is to bring attention to these works.

Why research Dada now?

The wars in Ukraine and Palestine keenly remind us that we are still living in times of war. How can we stand in solidarity in the face this reality? In this question lies the significance of learning about Dada’s pursuit of art-driven solidarity amid the First World War. Thinking about Dada’s transcendental qualities can provide us with practical hints for international society’s future. I believe that in dangerous times when politically motivated destruction is rationalized, Dada can be a field of study that provides hope.

The book I recommend

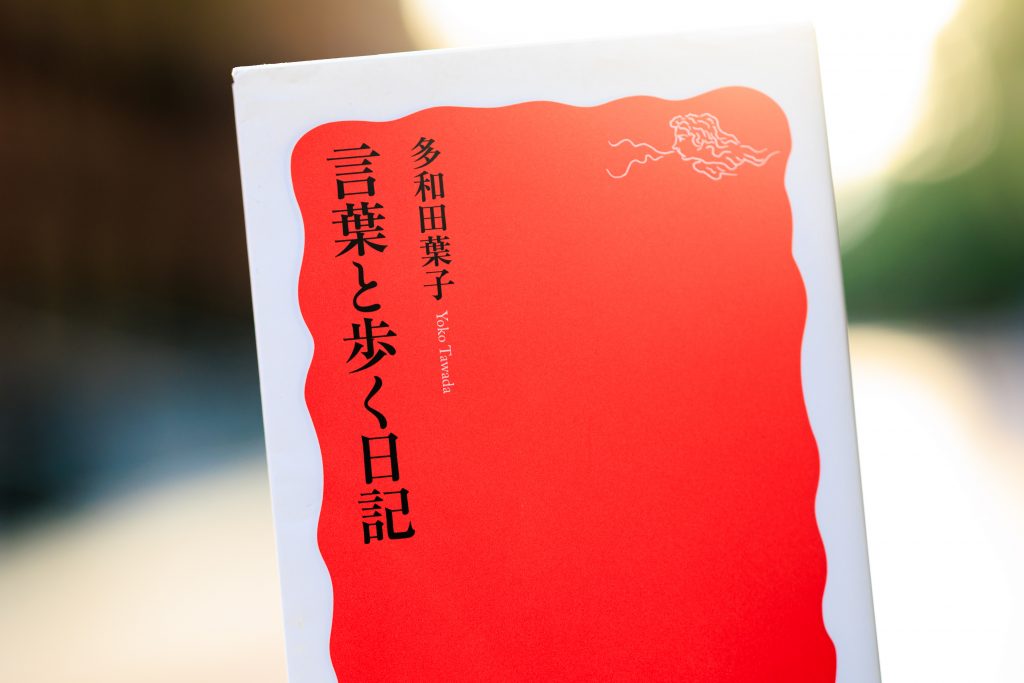

“Kotoba to Aruku Nikki” (A Diary of Words and Walking)

by Yoko Tawada, Iwanami Shinsho

I recommend this book to young people who are trying to learn a foreign language. The author, Yoko Tawada, does not confine herself to literature and is deeply involved in drama, opera, and other art forms. In this way, I feel like she shares the transcendental qualities of Dadaism. Learning a foreign language requires one to think about language itself, which is a crucial first step in crossing over.

-

Yuri Komatsubara

- Professor

Department of German Literature

Faculty of Humanities

- Professor

-

Komatsubara completed her undergraduate studies at the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies where she subsequently obtained her doctorate. She served as Associate Professor at Kanagawa University and later at Sophia University’s Faculty of Humanities, before assuming her current position in 2023.

- Department of German Literature

Interviewed: October 2024