Associate Professor Paula Martínez-Sirés of the Faculty of Foreign Studies analyzes methods for translating Japanese novels and manga into Spanish. Translations are a reflection of the times, prevailing cultures, and the relationships between the two countries; translation is also undergoing change in this era of globalization and AI.

My field of expertise is Translation Studies. I specialize in Spanish and Catalan, which is the official language of the Catalonia autonomous community of Spain. I research translations between these two languages and Japanese from the perspective of comparative culture.

I have analyzed more than 130 Spanish translations of Japanese manga. Until the 1980s, manga translations were bound on the left, in the Western style. Words unique to Japan such as “kotatsu” and “dorayaki” were replaced with English or Spanish approximations; in fact, in Captain Tsubasa, the name of the eponymous hero “Tsubasa” was changed to “Oliver.”

Since the 2000s onward, however, the number of right-bound books has increased, and uniquely Japanese words tend to appear in Romanized form.

The main translation style of the 1980s was “domestication”—a style in which priority was given to the language and culture of the audience. In the 2000s, however, the predominant style shifted to “foreignization”—a method in which the language and culture of the original text is prioritized.

Foreignization is thought to have gained traction on the back of closer ties between Japan and Spain, and from a desire on the part of Spanish readers to learn more about Japan.

Digital translations are more global in style

An increasing number of publishers are now publishing manga not only in paper form but in digital form, too. Through my research, I have ascertained that digital translations are not identical to their paper counterparts; some words and expressions are altered.

I looked at shojo manga that were also released in slide-show form as YouTube videos. The digital version is read by people in Spanish-speaking regions around the world—not only in Spain, but in Central and South America, and in other regions, too.

When I interviewed the translators of these digital versions, they explained that—like dialects—different Spanish words and expressions are used in different countries; and that they take such differences into account when translating digital versions.

As you can see, methods of translation not only vary from era to era, but are significantly impacted by the power balance between the country of origin and destination. It is fascinating to see what these translations reveal about international relations between the two countries; as such, I end up reading multiple novels and comics at the same time.

I also work as a translator. When I was starting out, I was often unsure how to translate different texts, and so I hope my research helps give clarity to fellow translators who are struggling with the same challenges.

Anonymous translators from the Meiji period

Going forward, I wish to study Japanese translators of Western texts from the Meiji period. Mori Ōgai is one of the more famous Meiji-era translators, but there were numerous other nameless translators as well—and it turns out that there were many women among them. I hope to explore how, exactly, women engaged in translation during this period of enlightenment.

While it is rare for much attention to be paid to translators, we can read translated books with such a sense of ease and enjoy translated movies because they have been translated so adeptly.

In recent years, much has been made of AI translations, but they are not yet a match for human translations when it comes to literature and manga. It is for this reason that I wish to pay respect to translators in my research and hope that light is thrown on their work.

The book I recommend

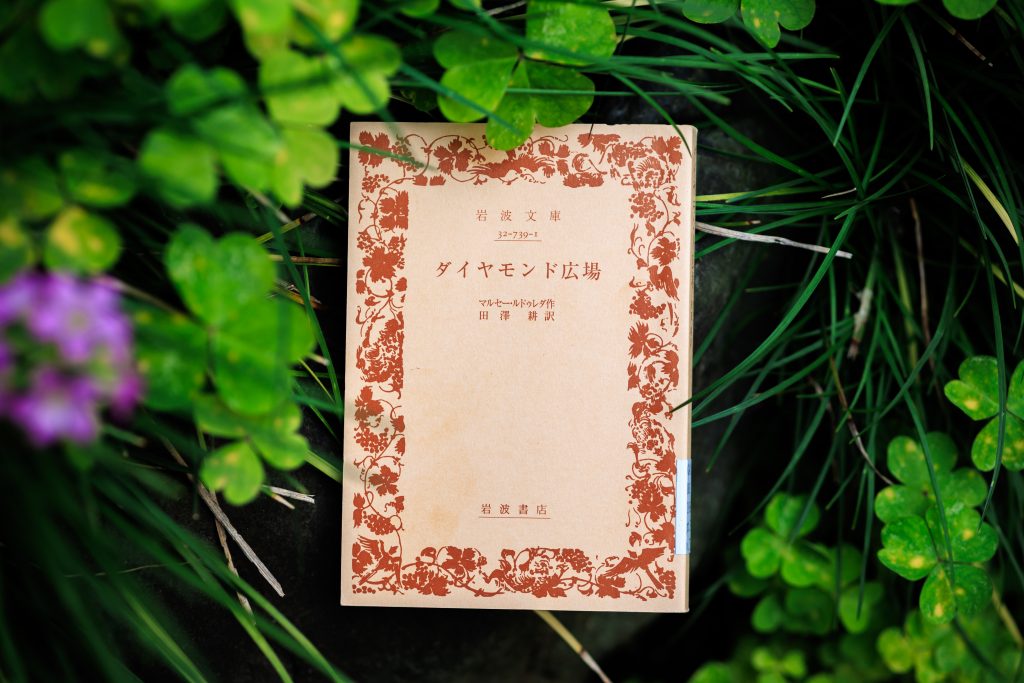

La plaça del diamant (In Diamond Square)

by Mercè Rodoreda, Japanese translation by Ko Tazawa, Iwanami Bunko

This novel about the tumult of the Spanish Civil War is written from the perspective of a woman. I read this book when I was a high school student, and it opened my eyes to the horrors of war. Yet the novel is known for its beautiful, letter-like literary style. This stylistic beauty comes across even in Japanese translation, and so I hope that it will be more widely read.

-

Paula Martínez-Sirés

- Associate Professor

Department of Hispanic Studies

Faculty of Foreign Studies

- Associate Professor

-

Associate Professor Paula Martínez-Sirés graduated from the Faculty of Translation and Interpreting, Autonomous University of Barcelona, and received her Ph.D. in International Culture and Communications Studies from the Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies, Waseda University. She worked as an Assistant Professor at the College of International Relations, Nihon University, before being appointed to her current position at Sophia University in 2025.

- Department of Hispanic Studies

Interviewed: June 2025