Society has preconceived notions about how men and women live, and about what constitutes the ideal family—but are these correct? In her research, Professor Toshiko Nonomura of the Faculty of Human Sciences focuses on how worldviews of women and of families have changed over time.

My area of expertise is the social history of education. I aim to elucidate historically the mechanisms by which worldviews thought to be self-evident by modern society—worldviews related to children, families, and genders—are formed.

This research is rooted in my own experiences as an employee at a private-sector company. Although I found employment shortly after the implementation of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, I felt that working women were expected to play a subservient role to working men—and that there was a close connection between the role expected of women in society and the role expected of women in the home. I questioned why this should be, and I determined that this was a theme worthy of research.

Initially, in my research I focused on what were considered by modern societies to be exemplary female lifestyles and ideal families. However, as I learned about how women and families were viewed by societies from before the modern period, I wanted to understand the history of how these views had changed over time.

The family model of the man as breadwinner and the woman as housewife in charge of housework and child-raising emerged as a status symbol for the middle class as societies underwent industrialization and modern civil society was established.

But how did this family model gain currency beyond the middle class? To answer this question, I am currently researching how concepts of the mother and the family were seen by those involved in relief for the poor in 18th century Britain.

How did the modern concept of the family spread?

In the 1700s, many members of the British middle and upper classes were involved in charity work, and they founded large numbers of clinics and lying-in hospitals that could be used free of charge by the poor.

The middle and upper classes had an affinity for the modern concept of the family. From publicity materials soliciting donations for charitable causes, as well as from reports detailing how such donations were used, it is possible to glean what requirements they imposed on poorer members of society seeking relief.

For example, lying-in hospitals could only be used by women who were married, while mothers wishing to use clinics for their children also had to abide by numerous rules. By picking such regulations apart, it is possible to trace how ideas of family and of gender-specific roles—which can only be realized by those with comfortable incomes—came to penetrate the lower rungs of society.

As society modernized, so medical environments were subject to change. At lying-in hospitals, for example, midwives were gradually replaced by male doctors. Records left behind by these midwives reveal their struggles with how the arrival of male doctors led to the lives of fetuses being prioritized over the physical wellbeing of their mothers.

Contemporary records show how such judgments on the relative value of different lives, and such views of the female body, gradually gained currency over time as new midwives replaced older midwives with less modern views.

Discontinuities over time, and liberation from the hold of the past

In Japan, it was during the Meiji period (1868–1912) that Western ideas of the modern family and of a good wife and mother gained popularity. Soon afterward, the term “bosei”—which translates as “motherliness”—came to be used. Of course, such concepts have had a significant influence on those of us alive today.

It is difficult to take an objective view of one’s own preconceptions. However, by learning about different concepts that prevailed in different eras, and by investigating how and when these concepts changed, it is possible to gain an understanding of how today’s norms were shaped.

By identifying discontinuities over time, my aim is to free society from the hold of the past.

The book I recommend

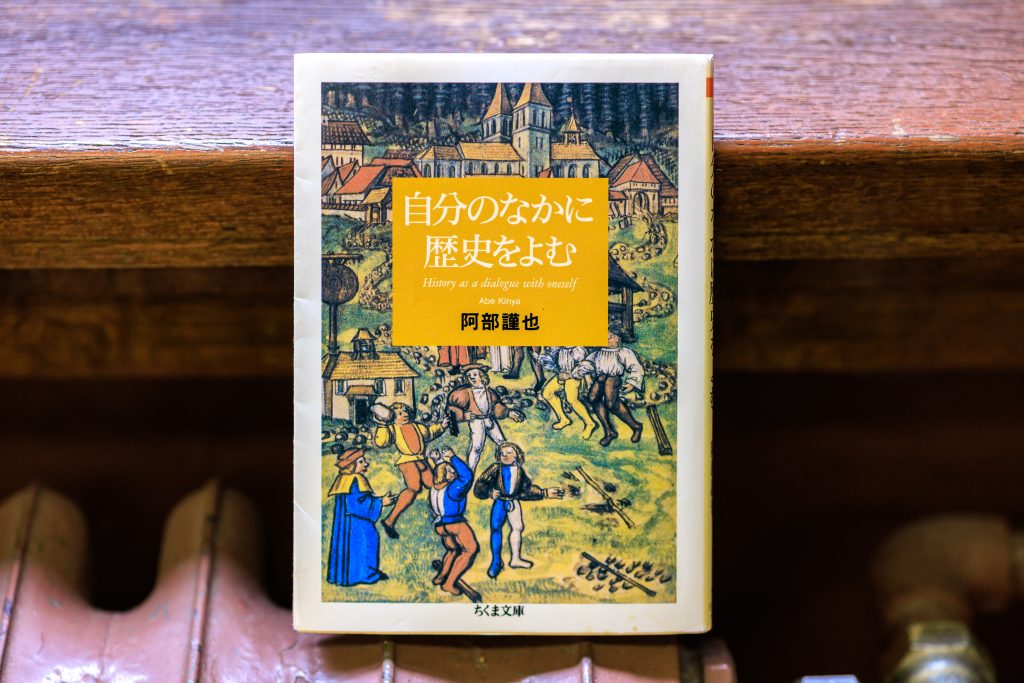

“Jibun no naka ni rekishi wo yomu”(History as a dialogue with oneself)

by Kinya Abe, Chikuma Bunko

This introduction to historical science for high school students was written by Kinya Abe, a leading authority in the field. As a university student, he was instructed by his tutor to choose a topic of study that he would be happy to dedicate his life to. He therefore began to research historical science as a way of shedding light on the doubts and apprehensions he had experienced growing up in a monastery. The book teaches us that by unraveling our pasts, we can find our calling.

-

Toshiko Nonomura

- Professor

Department of Education

Faculty of Human Sciences

- Professor

-

Professor Toshiko Nonomura graduated from the Faculty of Letters and Education, Ochanomizu University. After working in the private sector, she received her Ph.D. in education from the Graduate School of Education, the University of Tokyo. Nonomura worked as a lecturer then assistant professor at the School of Education, Kyushu University, and as an associate professor then professor at the Graduate School of Human-Environment Studies, Kyushu University. She was appointed to her current post in April 2025.

- Department of Education

Interviewed: June 2025