Naoko Morita of the Faculty of Humanities specializes in Francophone literature, Comparative literature, and the history of comics. She explores forms of literary expression that use both words and images, with a particular emphasis on Rodolphe Töpffer, the Swiss cartoonist who first drew comics in multi-panel sequences in the 19th century.

Humans have the ability to think about themselves, about other people, and about the real world through fictional stories, and they can also find comfort and redemption in these stories. The study of the literature is no less worthy than the study of the practical sciences—such a conviction has inspired my continued research into and teaching of literature.

Typically, literary studies entails researching a single, famous author. But rather than choosing a specific author, I wished to explore the cultures of reading and publishing more broadly; to begin with, I therefore researched novels serialized in newspapers and the illustrations that accompanied them.

In Japan, it is usual for serial novels to be accompanied by illustrations. On the other hand, there are no illustrations in France, where the serial novel originated—although there is a tradition of announcing the start of a new serial with an illustrated poster.

I developed an interest in the process by which, in using images in addition to words, publishers and newspapers made reading materials accessible to large numbers of people, including women and children.

International trends that influenced Japan’s manga culture

But why did the text-and-image format attract readers? I was in France trying to answer this question when I learned of Rodolphe Töpffer, the 19th century Swiss who created the first multi-panel-sequence comics. Töpffer ran a boarding school in French-speaking Geneva, and he created comical stories that combined drawings and text for his students.

In his works, the same characters appear from start to finish, and the causal relationships of a story are expressed through a sequence of drawings.

In Japan, manga tends to be considered a unique media form that can trace its roots back to the Choju-giga picture scrolls and the works of Hokusai; Osamu Tezuka is considered the father of the narrative manga. But Tezuka was influenced by Disney and, before Tezuka, the Asahigraph magazine featured translated versions of American comics as early as the 1920s. Evidently, the comic form is not unique to Japan.

Two international trends have had a significant impact on Japanese manga culture. The first is speech balloons, which featured for the first time in comics published in the Sunday editions of newspapers in the US in the 19th century. The second is the narrative comics, of which Töpffer’s comic strips are arguably the prototype.

His work gained popularity in Paris, and pirated versions were circulated in the UK and the US. There is a possibility they were imported to Japan as well.

“Narrative media” in the broadest sense

I began researching Töpffer when, after returning to Japan and taking a job at university, some students of mine told me they wished to study comics. This was around 2000, when comics were not yet considered a legitimate subject of literary studies.

In order to provide instruction to my students, I myself began to explore the birth of comics around the world. Afterward, together with Professor Koichi Morimoto of Tohoku University, I presided over the Association for Narrative Media Study.

The Association for Narrative Media Study uses academic methods to research narrative media that, traditionally, were not considered suitable for literary studies; examples include comics, animation, film, and children’s literature.

We still have notebooks containing Töpffer’s rough drafts, drawn by his own hand some 150 years ago. How did he view the world and think about things? What paper and drawing implements did he use to express his ideas?

One of the joys of literary studies is that we can enter into the time and space in which the writers of the past existed, and learn about the environments they inhabited and the values they held. And, in so doing, we can put our own lives in perspective.

The book I recommend

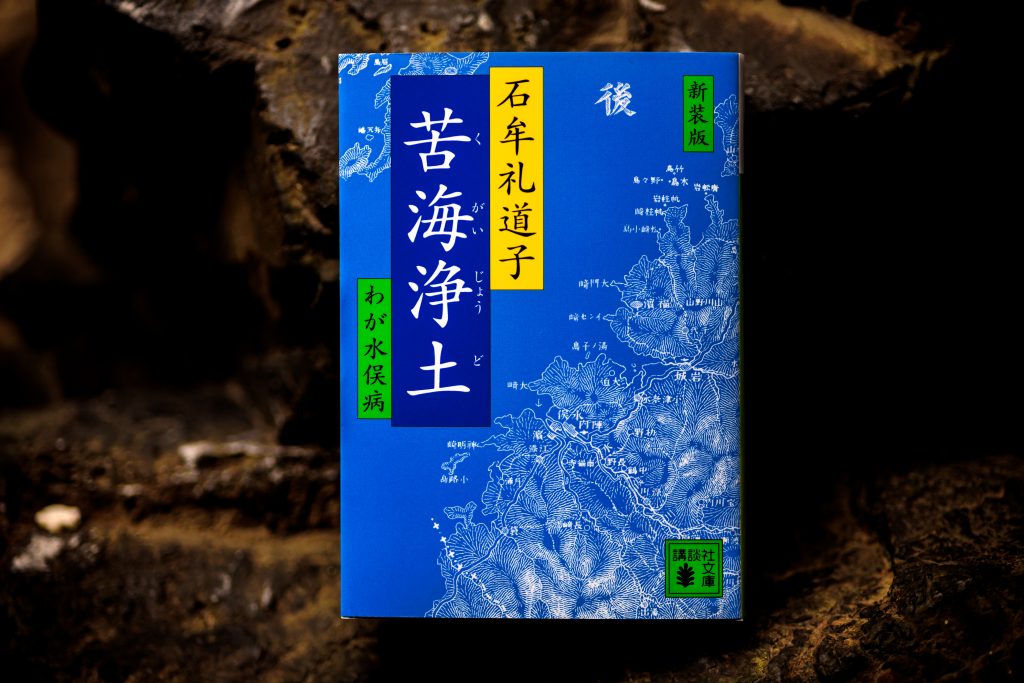

“Kugai jodo”(Paradise in the sea of sorrow)

by Michiko Ishimure, Kodansha Bunko

I once selected this challenging book as a textbook for a literature course open to all university departments. Ishimure’s words convey the weight of the silence and loneliness of the victims of Minamata Disease and their families, and they capture the importance of the sea in their lives. The book forces the reader to consider the conveniences our lifestyles are built upon.

-

Naoko Morita

- Professor

Department of French Literature

Faculty of Humanities

- Professor

-

Graduated from the College of Arts and Sciences, University of Tokyo, and obtained her master’s degree from the university’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. She received her Ph.D. in literature from Paris Diderot University. Worked as an assistant professor at the Faculty of Letters, Kumamoto University and as an associate professor at the Graduate School of Information Sciences, Tohoku University, before being appointed to her current post in 2025.

- Department of French Literature

Interviewed: June 2025